On the frosty morning of Dec. 9, 1921, in Dayton, Ohio, researchers at a General Motors lab poured a new fuel blend into one of their test engines. Immediately, the engine began running more quietly and putting out more power.

The new fuel was tetraethyl lead. With vast profits in sight – and very few public health regulations at the time – General Motors Co. rushed gasoline diluted with tetraethyl lead to market despite the known health risks of lead. They named it “Ethyl” gas.

It has been 100 years since that pivotal day in the development of leaded gasoline. As a historian of media and the environment, I see this anniversary as a time to reflect on the role of public health advocates and environmental journalists in preventing profit-driven tragedy.

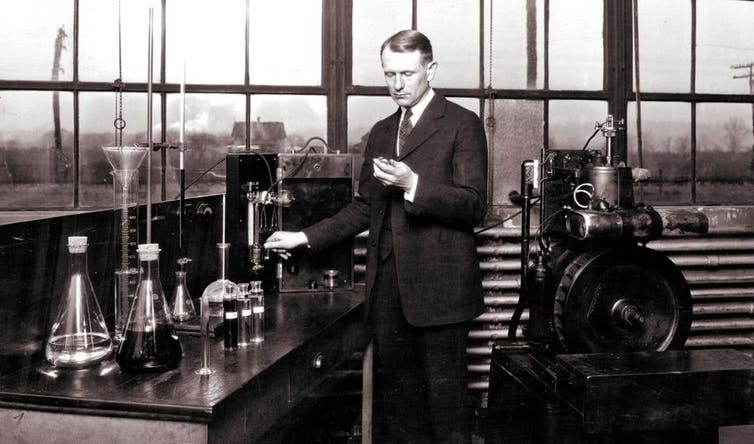

Scientists working for General Motors discovered that tetraethyl lead could greatly improve the efficiency and longevity of engines in the 1920s.

Courtesy of General Motors Institute

Lead and death

By the early 1920s, the hazards of lead were well known – even Charles Dickens and Benjamin Franklin had written about the dangers of lead poisoning.

When GM began selling leaded gasoline, public health experts questioned its decision. One called lead a serious menace to public health, and another called concentrated tetraethyl lead a “malicious and creeping” poison.

General Motors and Standard Oil waved the warnings aside until disaster struck in October 1924. Two dozen workers at a refinery in Bayway, New Jersey, came down with severe lead poisoning from a poorly designed GM process. At first they became disoriented, then burst into insane fury and collapsed into hysterical laughter. Many had to be wrestled into straitjackets. Six died, and the rest were hospitalized. Around the same time, 11 more workers died and several dozen more were disabled at similar GM and DuPont plants across the U.S.

The news media began to criticize Standard Oil and raise concerns over Ethyl gas with articles and cartoons.

New York Evening Journal via The Library of Congress

Fighting the media

The auto and gas industries’ attitude toward the media was hostile from the beginning. At Standard Oil’s first press conference about the 1924 Ethyl disaster, a spokesman claimed he had no idea what had happened while advising the media that “Nothing ought to be said about this matter in the public interest.”

More facts emerged in the months after the event, and by the spring of 1925, in-depth newspaper coverage started to appear, framing the issue as public health versus industrial progress. A New York World article asked Yale University gas warfare expert Yandell Henderson and GM’s tetraethyl lead researcher Thomas Midgley whether leaded gasoline would poison people. Midgley joked about public health concerns and falsely insisted that leaded gasoline was the only way to raise fuel power. To demonstrate the…