Can a monkey, a pigeon or a fish reason like a person? It’s a question scientists have been testing in increasingly creative ways – and what we’ve found so far paints a more complicated picture than you’d think.

Imagine you’re filling out a March Madness bracket. You hear that Team A beat Team B, and Team B beat Team C – so you assume Team A is probably better than Team C. That’s a kind of logical reasoning known as transitive inference. It’s so automatic that you barely notice you’re doing it.

It turns out humans are not the only ones who can make these kinds of mental leaps. In labs around the world, researchers have tested many animals, from primates to birds to insects, on tasks designed to probe transitive inference, and most pass with flying colors.

As a scientist focused on animal learning and behavior, I work with pigeons to understand how they make sense of relationships, patterns and rules. In other words, I study the minds of animals that will never fill out a March Madness bracket – but might still be able to guess the winner.

Logic test without words

The basic idea is simple: If an animal learns that A is better than B, and B is better than C, can it figure out that A is better than C – even though it’s never seen A and C together?

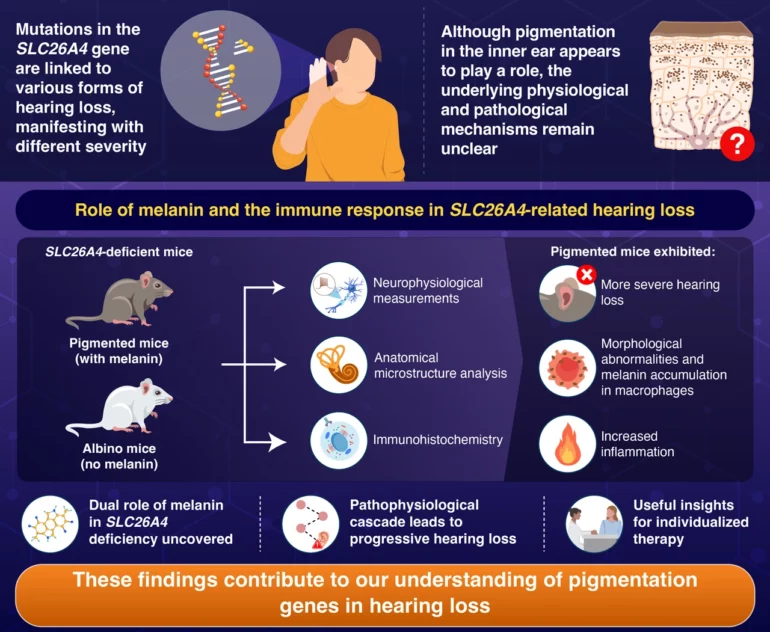

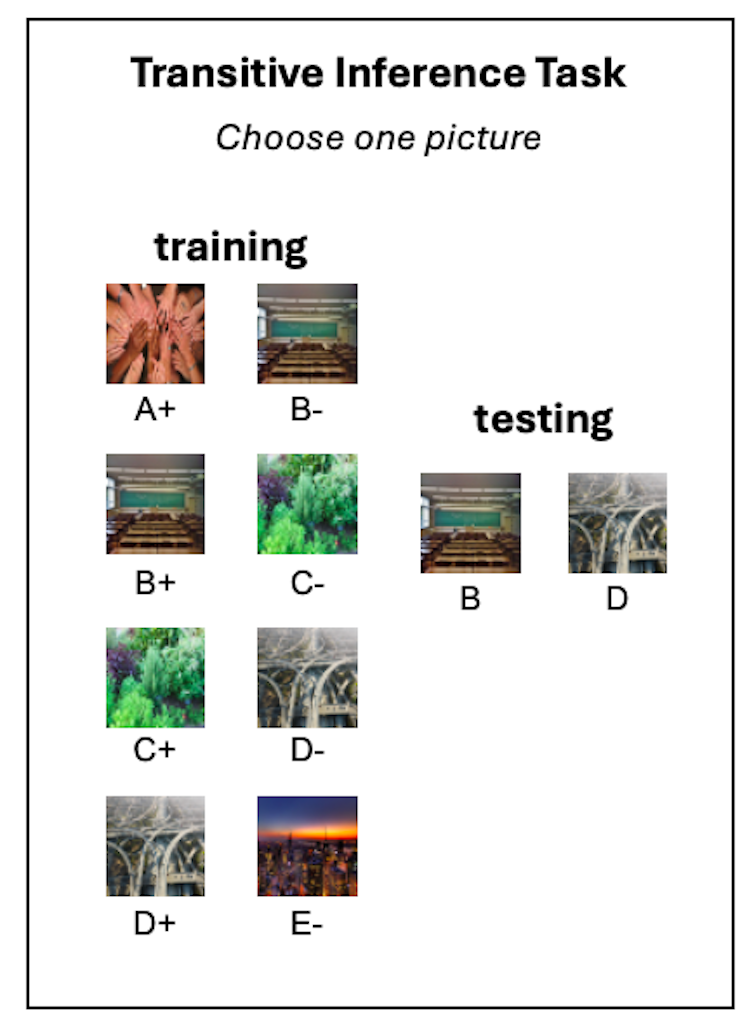

In the lab, researchers test this by giving animals randomly paired images, one pair at a time, and rewarding them with food for picking the correct one. For example, animals learn that a photo of hands (A) is correct when paired with a classroom (B), a classroom (B) is correct when paired with bushes (C), bushes (C) are correct when paired with a highway (D), and a highway (D) is correct when paired with a sunset (E). We don’t know whether they “understand” what’s in the picture, and it is not particularly important for the experiment that they do.

In a transitive inference task, subjects learn a series of rewarded pairs – such as A+ vs. B–, B+ vs. C– – and are later tested on novel pairings, like B vs. D, to see whether they infer an overall ranking.

Olga Lazareva, CC BY-ND

One possible explanation is that the animals that learn all the tasks create a mental ranking of these images: A > B > C > D > E. We test this idea by giving them new pairs they’ve never seen before, such as classroom (B) vs. highway (D). If they consistently pick the higher-ranked item, they’ve inferred the underlying order.

What’s fascinating is how many species succeed at this task. Monkeys, rats, pigeons – even fish and wasps – have all demonstrated transitive inference in one form or another.

The twist: Not all tasks are easy

But not all types of reasoning come so easily. There’s another kind of rule called transitivity that is different from transitive inference, despite the similar name. Instead of asking which picture is better, transitivity is about equivalence.

In this task, animals are shown a set of three…