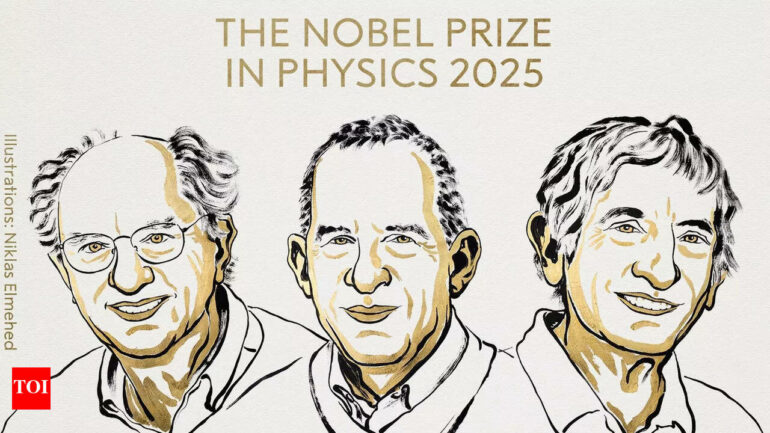

The 2025 Nobel Prize in physics honors three quantum physicists – John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis – for their study of quantum mechanics in a macroscopic electrical circuit.

Since the prize announcement, cheers and excitement have surrounded the home institutions of these laureates in Berkeley, Santa Barbara and New Haven.

The award of this prestigious prize to pioneering research in quantum physics coincides with the 100th anniversary of the birth of quantum mechanics – a revolutionary scientific theory that forms the foundation of modern physics.

Quantum mechanics was originally formulated to explain and predict the perplexing behaviors of atoms, molecules and subatomic particles. It has since paved the way for a wide range of practical applications, including precision measurement, laser technology, medical imaging and, probably the most far-reaching of all, semiconductor electronic devices and computer chips.

Yet numerous aspects of the quantum world have long remained mysterious to scientists and engineers. From an experimental point of view, the tiny scale of microscopic particles poses outstanding challenges for studying the subtle laws of quantum mechanics in laboratory settings.

The promises of quantum machines

Since the closing decades of the past century, researchers around the world have sought to precisely isolate, control and measure individual physical objects, such as single photons and atomic ions, that display quantum behaviors under very specific experimental conditions. These endeavors have given rise to the emerging field of quantum engineering, which aims to utilize the peculiarities of quantum physics for groundbreaking technological innovations.

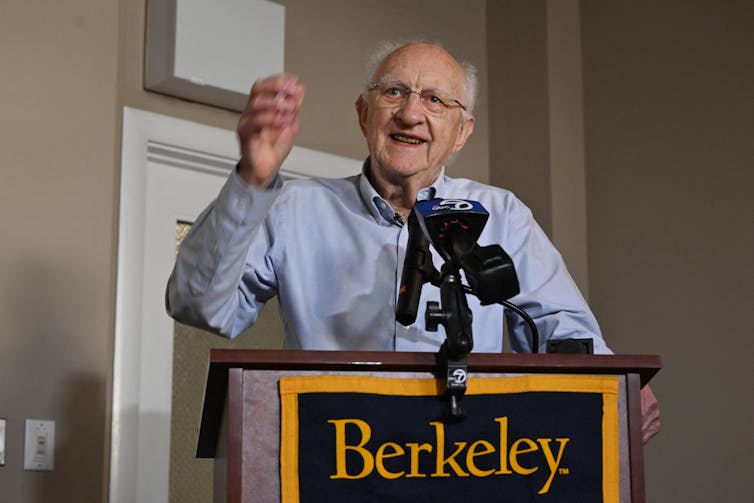

John Clarke, an emeritus professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, speaks on Oct. 7, 2025, at a press conference on the campus celebrating his 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Karl Mondon/AFP via Getty Images

One of the most promising directions is quantum information processing, whose goal is to design and implement machines that can encode, process, transmit and detect information in “strange” quantum manners: For instance, an object can be in a superposition of different states at the same time. Distant objects can manifest quantum entanglement – remote correlations that escape all possible classical interpretation. Compared with their conventional electronics predecessors, quantum information machines could have advantages in specific tasks of computation, simulation, cryptography and sensing.

The realization of such quantum machines would require experimenters having access to reliable physical components that can be assembled and controlled on the human scale, yet fully obey quantum mechanics. Counterintuitive as it might sound, can we break the implicit boundaries of the natural world and bring microscopic physical laws into the macroscopic reality?