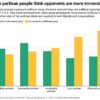

The virtue of intellectual humility is getting a lot of attention. It’s heralded as a part of wisdom, an aid to self-improvement and a catalyst for more productive political dialogue. While researchers define intellectual humility in various ways, the core of the idea is “recognizing that one’s beliefs and opinions might be incorrect.”

But achieving intellectual humility is hard. Overconfidence is a persistent problem, faced by many, and does not appear to be improved by education or expertise. Even scientific pioneers can sometimes lack this valuable trait.

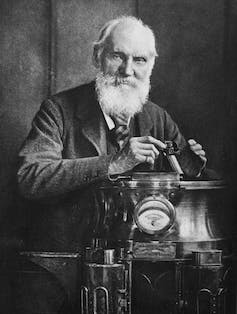

William Thomson, known as Lord Kelvin, poses in 1902 with his compass.

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Take the example of one of the greatest scientists of the 19th century, Lord Kelvin, who was not immune to overconfidence. In a 1902 interview “on scientific matters now prominently before the public mind,” he was asked about the future of air travel: “(W)e have no hope of solving the problem of aerial navigation in any way?”

Lord Kelvin replied firmly: “No; I do not think there is any hope. Neither the balloon, nor the aeroplane, nor the gliding machine will be a practical success.” The Wright brothers’ first successful flight was a little over a year later.

Scientific overconfidence is not confined to matters of technology. A few years earlier, Kelvin’s eminent colleague, A. A. Michelson, the first American to win a Nobel Prize in science, expressed a similarly striking view about the fundamental laws of physics: “It seems probable that most of the grand underlying principles have now been firmly established.”

Over the next few decades – in no small part due to Michelson’s own work – fundamental physical theory underwent its most dramatic changes since the times of Newton, with the development of the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics “radically and irreversibly” altering our view of the physical universe.

But is this sort of overconfidence a problem? Maybe it actually helps the progress of science? I suggest that intellectual humility is a better, more progressive stance for science.

Thinking about what science knows

As a researcher in philosophy of science for over 25 years and one-time editor of the main journal in the field, Philosophy of Science, I’ve had numerous studies and reflections on the nature of scientific knowledge cross my desk. The biggest questions are not settled.

How confident ought people be about the conclusions reached by science? How confident ought scientists be in their own theories?

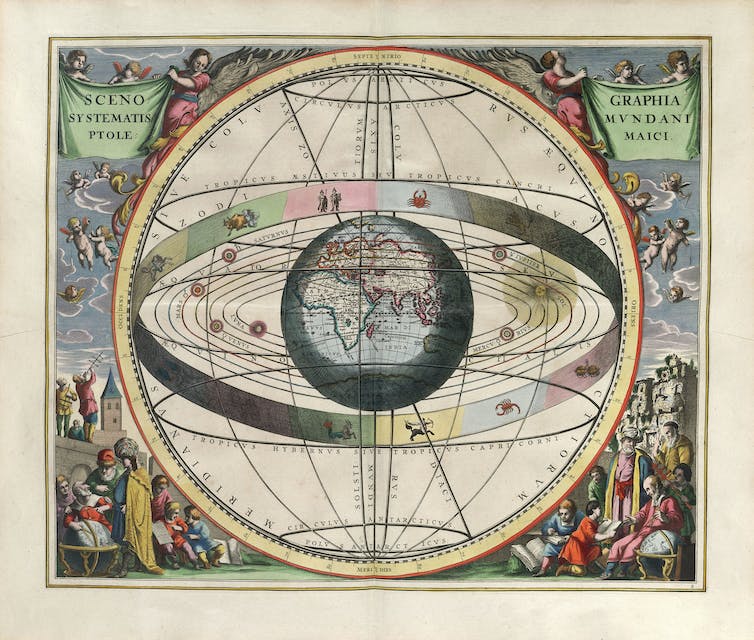

Eventually astronomy moved past the geocentric model of the universe with Earth at its center, which had stood for centuries.

VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

One ever-present consideration goes by the name “the pessimistic induction,” advanced most prominently in modern times by the philosopher Larry Laudan. Laudan pointed out…