During the years of suffering and tragedy that defined the Warsaw Ghetto in the midst of World War II, a team of Jewish doctors secretly documented the effects of starvation on the human body when the Nazis severely limited the amount of food available in the Jewish ghetto. The doctors collected this work in a book and, 80 years later, Merry Fitzpatrick rediscovered the brave efforts of these doctors hidden in a library at Tufts University, in Massachusetts in the U.S. In this Discovery episode of The Conversation Weekly, we speak to Fitzpatrick about how she found this piece of history, the story of its creation and how modern scientists are learning from the knowledge so bravely documented by the Jewish doctors.

Merry Fitzpatrick is an assistant professor at Tufts University who studies food security and malnutrition, especially in conflict zones. One day, she was searching through the school library and came across a book that she had never heard of in the basement.

“I went and pulled it off the shelf, and it was this crumbling little book. Its pages were just brown and brittle, and you could tell it hadn’t been opened in a long time,” she says. The foreword described the conditions of the Warsaw Ghetto and the anguish of doing research there. It was written by Israel Milejkowski, who Fitzpatrick calls the “Fauci of the ghetto”, after the former chief medical advisor to the U.S. president Anthony Fauci.

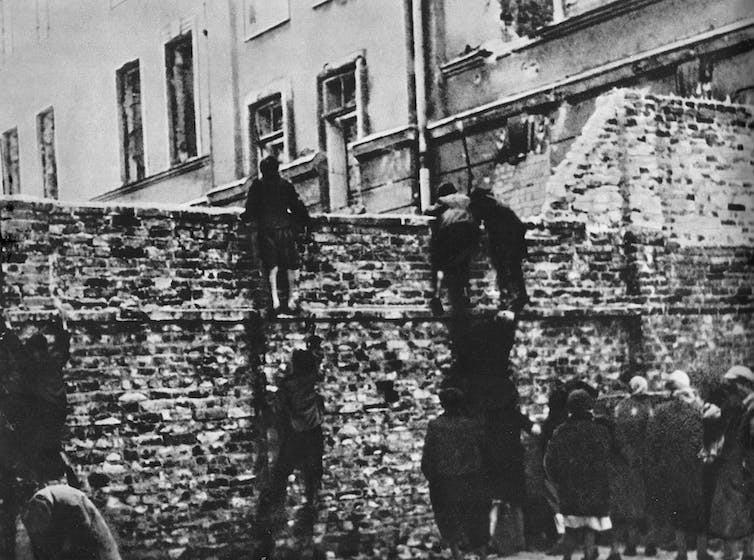

Smuggling was how most people in the ghetto got food, and children were often the ones sneaking out of the ghetto to do it.

nieznany/unknown via Wikimedia Commons

Over the course of 1941 and 1942, Milejkowski and his colleagues saw an opportunity to produce something good from the horrors of the Nazi-controlled ghetto. The lack of food was extreme. “The Jews were given a ration of 180 calories a day at one point. That’s like half a cookie,” says Fitzpatrick. As the doctors took care of the Jewish population in the ghetto – including their friends and colleagues – they documented the effects of starvation, too. These doctors then collected their research into the book that Fitzpatrick found.

Even today, the research done by the Jewish doctors is shedding light on some mysteries within the field of starvation and malnutrition research. Tuberculosis was very common in the ghetto, but when the doctors would test starving children with obvious symptoms of tuberculosis, the tests would often come back negative. As Fitzpatrick explains, “What it was was that in starvation, the body pretty much gives up on immunity – that’s not the priority. So when you do a test, you’re looking for an immune response that isn’t there.”

To find out how this idea is helping Fitzpatrick better understand HIV in malnourished children and the rest of Milejkowski’s story, tune in to this week’s episode of The Conversation Weekly.

This episode was produced by Mend Mariwany and…