About 87 million miles (140 million kilometers) above the Grand Canyon, an even larger, grander abyss cuts through the gut of the Red Planet. Known as Valles Marineris, this system of deep, vast canyons runs more than 2,500 miles (4,000 km) along the Martian equator, spanning nearly a quarter of the planet’s circumference. This gash in the bedrock of Mars is nearly 10 times as long as Earth’s Grand Canyon and three times deeper, making it the single largest canyon in the solar system — and, according to ongoing research from the University of Arizona (UA) in Tucson, one of the most mysterious.

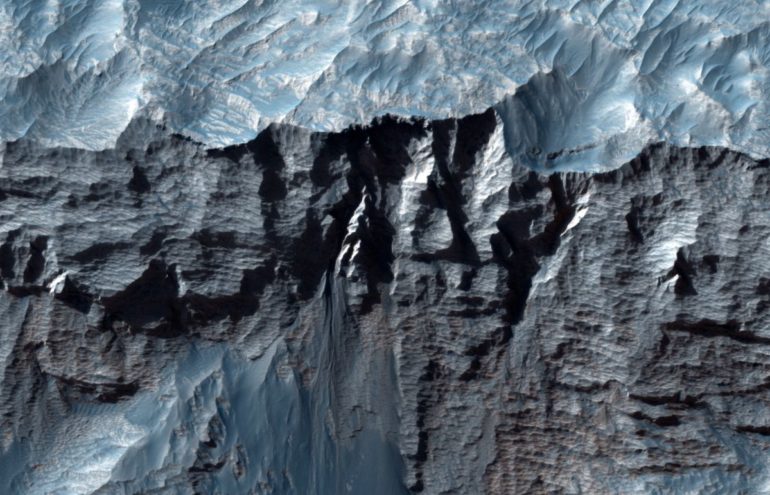

Using an incredibly high-resolution camera called HiRISE (short for High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment) aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, UA scientists have been taking close-up shots of the planet’s strangest features since 2006. Despite some truly breathtaking images of Valles Marineris — like the one below, posted to the HiRISE website on Dec. 26, 2020 — scientists still aren’t sure how the gargantuan canyon complex formed.

Unlike Earth‘s Grand Canyon, Valles Marineris probably wasn’t carved out by billions of years of rushing water; the Red Planet is too hot and dry to have ever accommodated a river large enough to slash through the crust like that — however, European Space Agency (ESA) researchers have said, there is evidence that flowing water may have deepened some of the canyon’s existing channels hundreds of millions of years ago.

A majority of the canyon probably cracked open billions of years earlier, when a nearby super-group of volcanoes known as the Tharsis region was first thrusting out of the Martian soil, the ESA said. As magma bubbled up beneath these monster volcanoes (which include Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system), the planet’s crust easily could have stretched, ripped and finally collapsed into the troughs and valleys that make up Valles Marineris today, according to the ESA.

Evidence suggests that subsequent landslides, magma flows and, yes, even some ancient rivers probably contributed to the canyon’s continued erosion over the following eons. Further analysis of high-resolution photos like these will help solve the puzzling origin story of the solar system’s grandest canyon.

Originally published on Live Science.