Nothing calls to mind nonsensical treatments and bizarre religious healing rituals as easily as the notion of Dark Age medicine. “The Saturday Night Live” sketch Medieval Barber Theodoric of York says it all with its portrayal of a quack doctor who insists on extracting pints of his patients’ blood in a dirty little shop.

Though the skit relies on dubious stereotypes, it’s true that many cures from the Middle Ages sound utterly ridiculous – consider a list written around 800 C.E. of remedies derived from a decapitated vulture. Mixing its brain with oil and inserting that into the nose was thought to cure head pain, and wrapping its heart in wolf skin served as an amulet against demonic possession.

“Dark Age medicine” is a useful narrative when it comes to ingrained beliefs about medical progress. It is a period that stands as the abyss from which more enlightened thinkers freed themselves. But recent research pushes back against the depiction of the early Middle Ages as ignorant and superstitious, arguing that there is a consistency and rationality to healing practices at that time.

As a historian of the early Middle Ages, roughly 400 to 1000 C.E., I make sense of how the societies that produced vulture medicine envisioned it as one component of a much broader array of legitimate therapies. In order to recognize “progress” in Dark Age medicine, it is essential to see the broader patterns that led a medieval scribe to copy out a set of recipes using vulture organs.

The major innovation of the age was the articulation of a medical philosophy that validated manipulating the physical world because it was a religious duty to rationally guard the body’s health.

Reason and religion

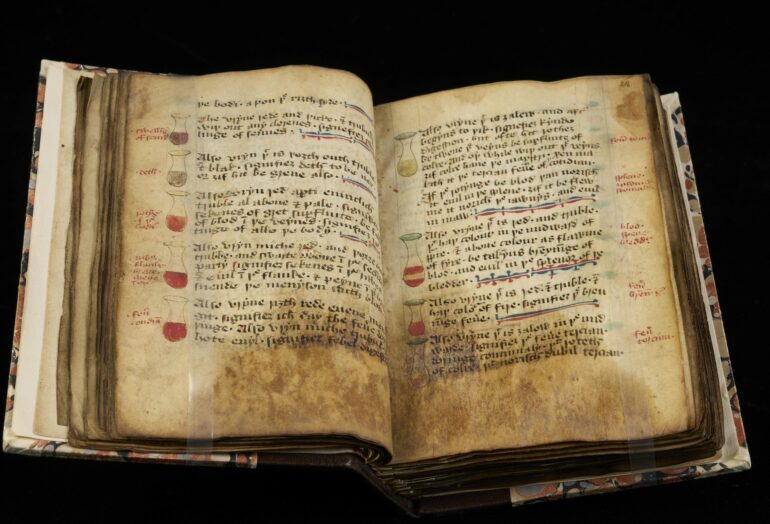

The names of classical medical innovators like Hippocrates and Galen were well known in the early Middle Ages, but few of their texts were in circulation prior to the 13th century. Most intellectual activities in northern Europe were taking place within monasteries, where the majority of surviving medical writings from that time were written, read, discussed and likely put into practice. Scholars have assumed that religious superstition overwhelmed scientific impulse and the church dictated what constituted legitimate healing – namely, prayer, anointing with holy oil, miracles of the saints and penance for sin.

However, “human medicine” – a term affirming human agency in discovering remedies from nature – emerged in the Dark Ages. It appears again and again in a text monks at the monastery of Lorsch, Germany, wrote around the year 800 to defend ancient Greek medical learning. It insists that Hippocratic medicine was mandated by God and that doctors act as divine agents in promoting health. I argue in my recent book, “Embodying the Soul: Medicine and Religion in Carolingian Europe,” that a major innovation of that time was the creative synthesis of Christian orthodoxy with a growing belief in the importance of preventing…