Archaeologists have analyzed textiles from the ancient city of Huacas de Moche, Peru, showing how the population’s cultural traditions survived in the face of external influence.

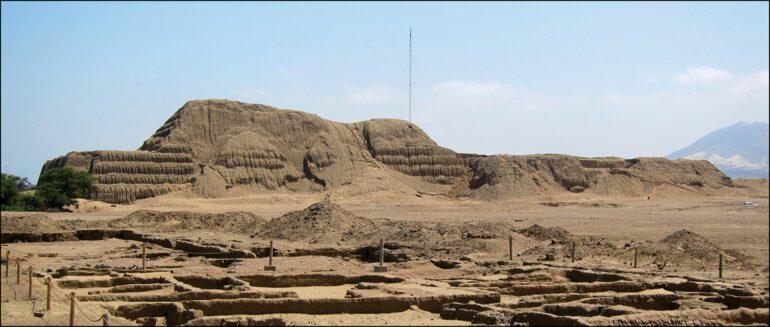

After the Inca, the Moche culture is one of the best-known archaeological cultures of the Andes. It is famed for its colorful temple complexes, the biggest of which, Huacas del Sol in Huacas de Moche, one of the largest known Moche sites, may have been the largest structure in the New World at its peak (c. AD 650–900).

Despite this, relatively little is known about what caused the end of the Moche culture. It has often been proposed that it was erased through the expansion of the powerful Wari Empire.

“The people who built Huacas de Moche, now known as the Moche (a.k.a. the Mochicas), are only known to us through archaeology as they had no writing system,” says lead author Dr. Jeffrey Quilter from Harvard University’s Peabody Museum.

“The date range for when the Moche culture existed has been debated for many decades.”

To attempt to determine the end date for the Moche culture, a team of researchers from several North and South American institutions, including the National University of Trujillo, analyzed and dated material culture from Huacas de Moche, with a particular focus on textiles. The work is published in the journal Antiquity.

“Our research involved our wrestling with the thorny and complicated issue of how ancient people identified themselves,” states Dr. Quilter. “In brief, when did the Moche stop being Moche at the site of Huacas de Moche?”

By analyzing production techniques and styles of the textiles, they determined that the majority were made using Moche techniques, but often contained design influences from other cultures, most notably the expansive Wari Empire from the southern highlands of Peru.

Radiocarbon dating of these textiles found that they date well into the tenth century AD, considerably later than previous estimations. This suggests that a sense of Moche identity may have persisted longer than previously thought. Importantly, these findings highlight the resilience of the Moche culture while also adapting to foreign influences.

Whether the people who both retained old ways and adapted to new ones thought of themselves as Moche, however, cannot be determined with certainty through archaeology.

This calls into question the way we view archaeological cultures. The Moche culture may not have ‘ended’ in a definitive sense, wiped out by the expansion of a ‘stronger’ neighbor, neither by a climate phenomenon. Instead, the culture transformed over time as a result of interaction with different peoples.

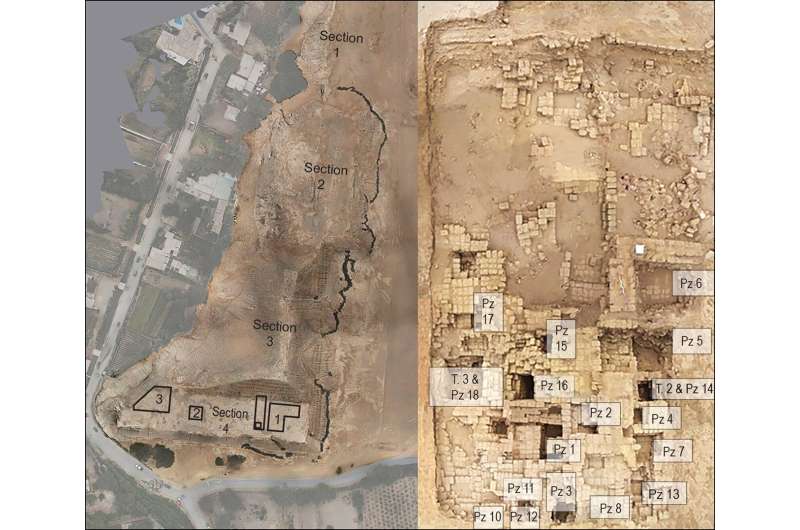

Left) aerial view of Huaca del Sol annotated with Sections 1–4 and excavation units in Section 4; right) detail of level 2 features in the western portion of excavation unit 1. © Authors, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.138

“Our research indicates that longstanding Moche material cultural practices and styles continued to be valued at Huacas de Moche, long after the presumed end of the archaeological culture,” says Dr. Carlos Rengifo from the National University of Trujillo.

“Even as the world about them changed, some sense of Moche identity appears to have been maintained.”

It also highlights the difficulties of examining past cultural identity without written evidence.

“Until recently, it is likely that no one referred [to] themselves as Moche,” concludes Dr. Quilter.

“Nevertheless, the archaeological culture that we call Moche clearly represents a distinct socio-cultural phenomenon and identity for those people who participated in it. Just as determining the cultural identity of any prehistoric community is fraught with difficulties, so too is identifying how they came to take on a new one.”

More information:

Jeffrey Quilter et al, Textiles, dates and identity in the late occupation of the Huacas de Moche, Peru, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.138

Citation:

1,000-year-old textiles reveal cultural resilience in the ancient Andes (2024, September 24)