Since the beginning of journalism in America, newspapers have been funded by advertising. In the 18th century, alongside advertisements for shoe repair, corduroys, and cutlery, colonial newspapers sold and ran ads for enslaved and unfree men, women, and children, usually in the form of “runaway” and “to be sold” ads.

These advertisements show something that scholarship on early American slavery has not always fully acknowledged, says Anjali DasSarma, doctoral student at the Annenberg School for Communication. Along with Linford Fisher at Brown University, the two show that the presence of enslaved and unfree Indigenous people was ubiquitous in the American colonies as late as the 19th century, long after the peak of the African slave trade.

In a new paper, published in Slavery & Abolition, DasSarma and Fisher use a century of these ads, from 1704 to 1804, to trace the presence of Indigenous slavery in homes and on plantations throughout the American colonies and to explore the connection between journalism and slavery.

Archives and advertisements

“This study was inspired by two projects,” says DasSarma. “Fisher is the Principal Investigator of Stolen Relations, which collects stories of indigenous enslavement, and I am deeply inspired by Freedom on the Move, which gathers ‘runaway’ newspaper advertisements about enslaved people in America.”

In “runaway” and “to be sold” ads, enslavers and slave brokers shared descriptions of the individuals they wished to be “returned” or were putting up for sale. Indigenous people were often referred to as “Indian” or a person with an “Indian look.” The earliest “runaway” advertisement referencing an Indigenous person was printed in a 1704 issue of the Boston News-Letter:

“Ran away from Capt. John Aldin of Boston, on Monday the 12th Currant, a tall lusty Indian Man call’d Harry, about 19 Years of Age, with a black Hat, brown Ozenbridge Breeches and Jacket: Whoever will take up said Indian, and bring or convey him safe either to John Campbell Post master of Boston, or to Mr. Nathaniel Niles of Kingstown in Naraganset, Master to said Indian, shall have a sufficient Reward.”

DasSarma uncovered this ad in a database of historical newspapers after months of combing through every ad that mentioned the word “Indian” between the years 1704 and 1804. There were over 75,000 of these in this database alone, which doesn’t include every paper published during that time period.

Many of these ads were used to sell goods like “Indian blankets” and “Indian corn,” but 1,066 advertised enslaved and unfree Indigenous people.

The scope of indigenous slavery

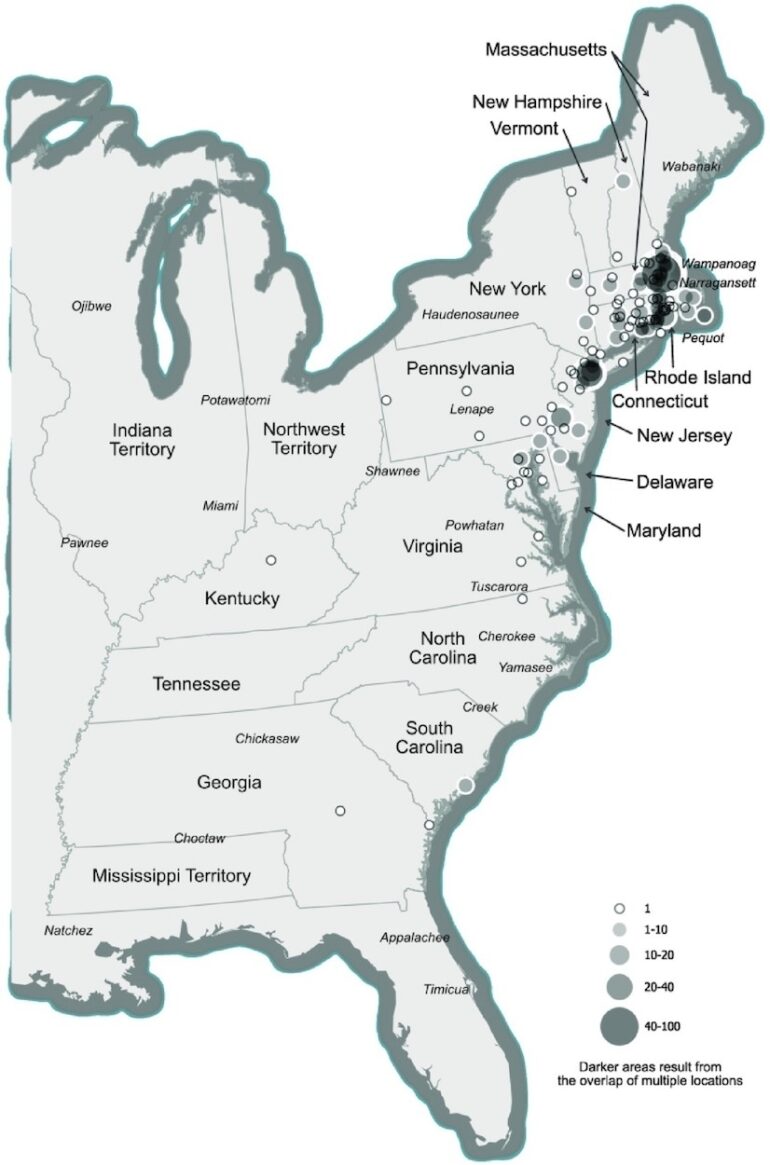

The researchers used these ads to track the number of published advertisements by year and map the locations noted.

“We found ads for enslaved and unfree Indigenous individuals in every one of the original 13 colonies,” DasSarma says. “And there was a surprising consistency in the number of ads placed between 1704 and 1804. Indigenous slavery didn’t taper off after the American Revolution.”

“Our analysis of these advertisements reveal an overlooked and important aspect of the history of this country,” says Fisher. “America was not only built on Native American land, it was also built on the backs of Native American laborers, who were enslaved by the tens of thousands and who worked alongside enslaved Africans on plantations and in households well into the nineteenth century.”

National narratives and academic histories need to be revised to recognize this fact, they say.

The complicity of journalism

DasSarma, who studies the history of journalism, is interested in how early American newspapers’ participation in the business of slavery factors into the relationship between communities of color and journalism today.

“There is a historic and contemporary distrust of newspapers within communities of color that can be traced, in my opinion, directly back to these types of advertisements.” she says.

Not only did newspaper printers directly profit from slavery by charging for these ads, but they also perpetuated the idea that slavery was acceptable.

“In a way, printers themselves acted as slave brokers by facilitating the buying and selling of people,” DasSarma says.

She points out that “runaway” ads are framed as calls to action, encouraging everyday newspaper readers to become slave catchers. Readers are promised rewards for the “return” of enslaved and unfree Indigenous individuals and some ads even warned that “runaway” slaves might “pretend to be free.”

One ad reads:

“RUN-AWAY from the subscriber, living at New Lots, King’s county, on Long-Island, the 16th instant, a negro fellow named NAT; has lost his right eye, about 24 years old, pitted with the small-pox, 5 feet 8 inches high, Indian hair, and of a yellow complexion: Had on when he went away, a whitish surtout coat, a homespun coat, and light colored jacket-Whoever takes up and secures the said fellow, so that he may be had again, shall receive Five Dollars reward, and all reasonable charges, paid by HENRY WICKOFF.”

This framing encouraged readers to constantly question the freedom and trustworthiness of Indigenous and Black citizens, DasSarma says, something she sees in crime reporting today.

“I think pointing to the complicity of newspapers in slavery is really important,” DasSarma says. “When you open a newspaper, you’re promised truth, and in the 1700s, you opened a newspaper and saw people being advertised.”

More information:

Anjali DasSarma et al, The Persistence of Indigenous Unfreedom in Early American Newspaper Advertisements, 1704–1804, Slavery & Abolition (2023). DOI: 10.1080/0144039X.2023.2189517

Provided by

University of Pennsylvania

Citation:

A century of newspaper ads shed light on Indigenous slavery in colonial America (2023, April 28)