Around 700 BC, the Neo-Assyrian emperor Sargon II began building a new capital city, named after himself, in the desert of what is now Iraq. Archaeologists have long thought this grandiose project had barely gotten underway when it was abandoned, leaving only the ruins of a construction zone. But a newly published survey of the site upends that idea. Visualizations of data from a precision magnetometer show previously unknown buildings and infrastructure within the city walls, suggesting that the city indeed thrived beyond the palace.

The findings were presented today at AGU’s 2024 Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., where more than 28,000 scientists will gather to discuss the latest in Earth and space research.

Sargon II died a few years after work began on Dur-Sharrukin (“Fortress of Sargon”), now called Khorsabad. His son quickly set up his own capital in the city of Nineveh, and for the next 2,500 years, Sargon II’s building project was largely forgotten.

In the 1800s, French archaeologists rediscovered the site. Their excavation of Sargon’s palace uncovered treasures of Neo-Assyrian art and culture, but teams digging elsewhere in the city came up empty-handed. Archaeologists concluded that the palace was the only building begun within Khorsabad’s city walls, which enclose an area more than one mile square (1.7 by 1.7 square kilometers).

When a two-year occupation of Khorasbad by the Islamic State officially ended in 2017, the French Archaeological Mission at Khorsabad decided to undertake a new initiative both to assess above-ground damage and to make the first geophysical survey of buried remains at the site. They hoped the survey would uncover the city’s water infrastructure, reveal new details about the fortifications on the walls, and possibly even find new traces of settlement outside the palace.

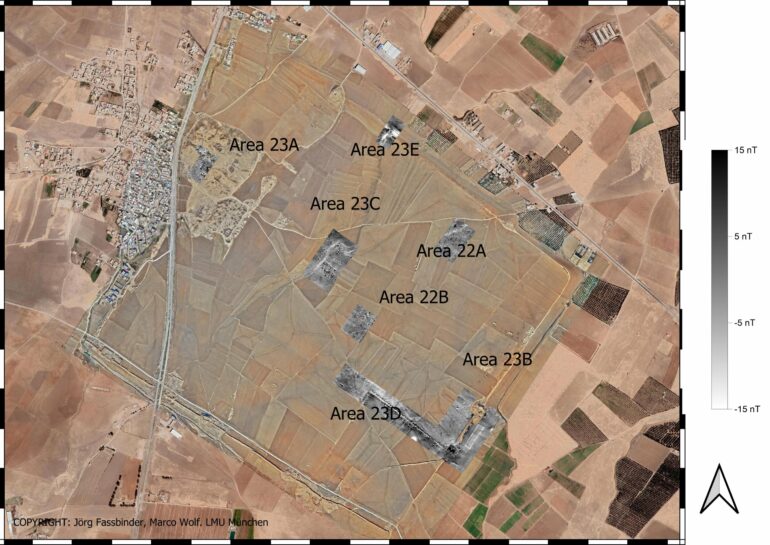

In 2022, Jörg Fassbinder of Ludwig-Maximilians-University and colleagues from Near Eastern Archaeology, Panthéon Sorbonne University, and the University of Strasbourg mapped about 7% of the city area using a high-resolution magnetometer, which is “like having an X-ray of features beneath the ground,” Fassbinder said. Different types of soil, rock, and other materials have distinctive magnetic properties that the magnetometer detects. For example, a pavement made of limestone blocks has a different magnetic signal than baked bricks used in ancient construction.

To keep a low profile while completing the magnetic survey in the turbulent region, the team didn’t mount their magnetometers on a drone or a vehicle that might attract attention. Instead, Fassbinder and another researcher hand-carried the 33-pound (15-kilogram) instruments over the site, walking in long, straight lines to cover a total area of 2.79 million square feet—still less than 10% of the huge site. Fassbinder estimates they each walked more than 13 miles (20 kilometers) every day for seven days to complete the survey.

The results were worth the effort.

“Every day we discovered something new,” Fassbinder said. When the data were visualized as grayscale images, ghostly outlines emerged of structures as deep as six to ten feet (two to three meters) below ground. The data revealed the location of the city’s water gate, possible palace gardens, and five enormous buildings, including a 127-room villa twice the size of the U.S. White House. These and other discoveries are evidence that, at least for some time, Khorsabad was a living city.

“All of this was found with no excavation,” Fassbinder pointed out. “Excavation is very expensive, so the archaeologists wanted to know in detail what they could expect to achieve by digging. The survey saved time and money. It’s a necessary tool before starting any excavation.”

More information:

Abstract: agu.confex.com/agu/agu24/meeti … pp.cgi/Paper/1663117

Provided by

American Geophysical Union

Citation:

Abandoned Assyrian capital brought to life in new magnetic survey (2024, December 9)