Archaeologists analyzed thirteenth century BC bronze and flint arrowheads from the Tollense Valley, north-east Germany, uncovering the earliest evidence for large-scale interregional conflict in Europe. The Tollense Valley in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania is well-known as the site of a large conflict dating to c. 1250 BC.

The quantity of human remains found (more than 150 individuals) suggests over 2,000 people were involved, an amount unprecedented for the Nordic Bronze Age. First proposed to be a battlefield in Antiquity in 2011, nowadays the site is often referred to as “Europe’s oldest known battlefield,” since no other conflict of this scale has been discovered that dates earlier.

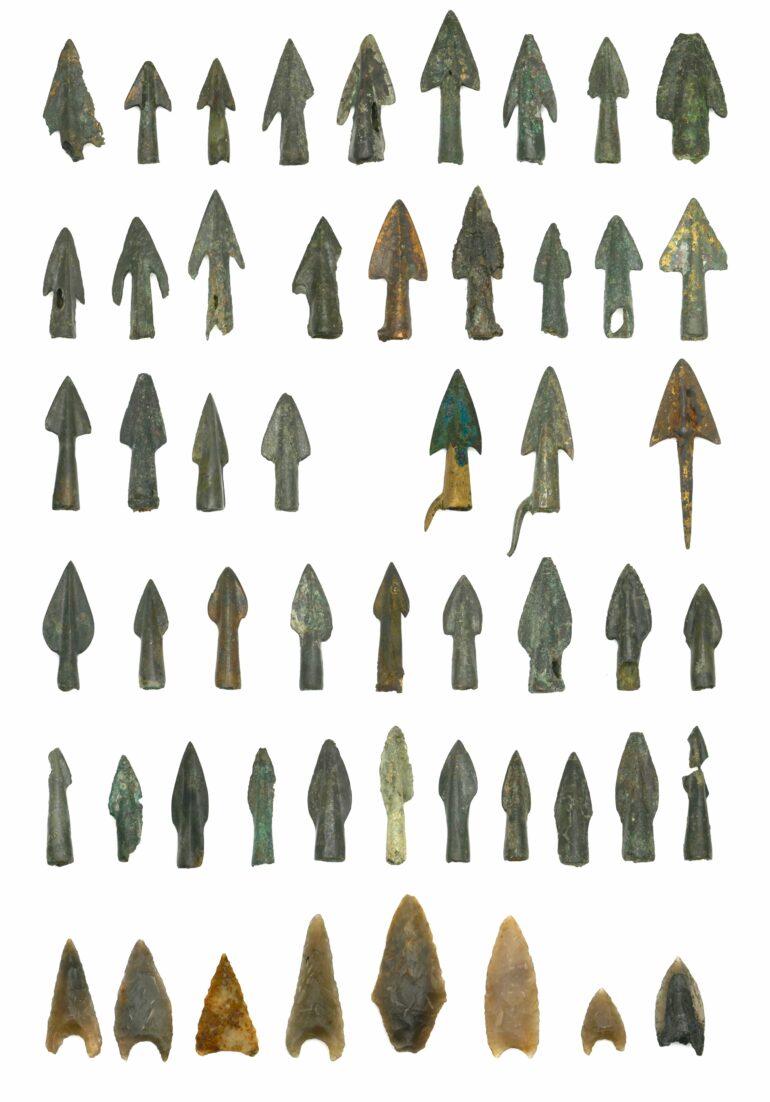

However, very little is known about the people who fought and died at Tollense over 3,000 years ago. Who was involved in the battle, and where did they come from? To answer these questions, a team of researchers from several German institutions compared bronze and flint arrowheads found in the valley with over 4,000 contemporary examples from across Europe.

Their results are published in the journal Antiquity.

“The arrowheads are a kind of ‘smoking gun,'” says lead author of the research, Leif Inselmann, who collected more than 4,700 arrowheads from Central Europe for his M.A. thesis at Göttingen University. “Just like the murder weapon in a mystery, they give us a clue about the culprit, the fighters of the Tollense Valley battle and where they came from.”

The majority of the arrowheads are of types occasionally found in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, suggesting that most of the people who fought at Tollense were relatively local. However, other types such as arrowheads with straight or rhombic bases, with unilateral barbs or with a pointed tang instead of a socket are better known from a region to the south that encompasses modern Bavaria and Moravia.

These types of arrowheads have not been found in burials from the Tollense region, indicating that local people were not simply acquiring the arrowheads through trade with the south and using them in battle themselves.

This suggests that at least some of the people fighting at Tollense were not from the area, implying southern warriors, or perhaps even a southern army, were involved in the conflict.

At several contemporary sites in southern Germany, large amounts of bronze arrowheads were found as well, suggesting that the thirteenth century BC was a period of European prehistory that saw an overall increase in armed conflict. Importantly, this is also the earliest example of interregional conflict in Europe, implying this period corresponded with increased scale and professionalization of organized violence.

“The Tollense Valley conflict dates to a time of major changes,” concludes Inselmann, now at the Freie Universität Berlin. “This raises questions about the organization of such violent conflicts. Were the Bronze Age warriors organized as a tribal coalition, the retinue or mercenaries of a charismatic leader—a kind of ‘warlord,’ or even the army of an early kingdom?”

More information:

Leif Inselmann et al, Warriors from the south? Arrowheads from the Tollense Valley and Central Europe, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.140

Citation:

Archaeologists discover southern army fought at ‘Europe’s oldest battle’ (2024, September 24)