Ancient symbols on a 2,700-year-old temple, which have baffled experts for more than a century, have been explained by Trinity Assyriologist Dr. Martin Worthington.

The sequence of “mystery symbols” was on view on temples at various locations in ancient city of Dūr-Šarrukīn, present-day Khorsabad, Iraq, which was ruled by Sargon II, king of Assyria (721–704 BC).

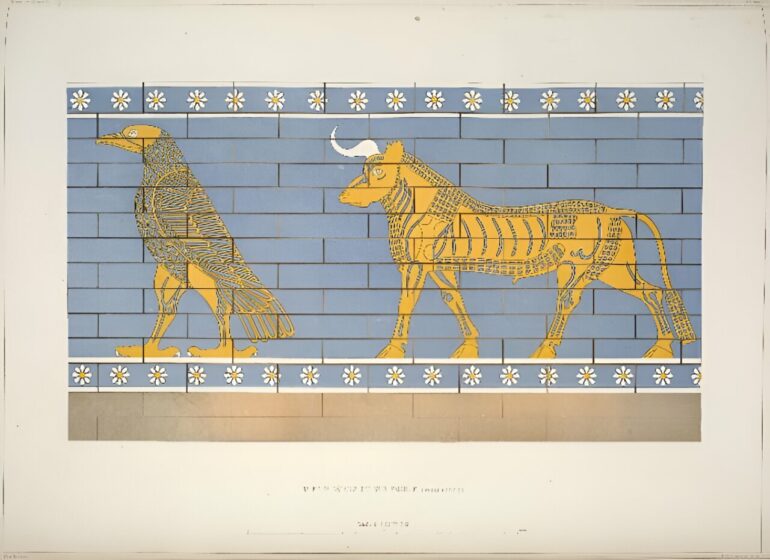

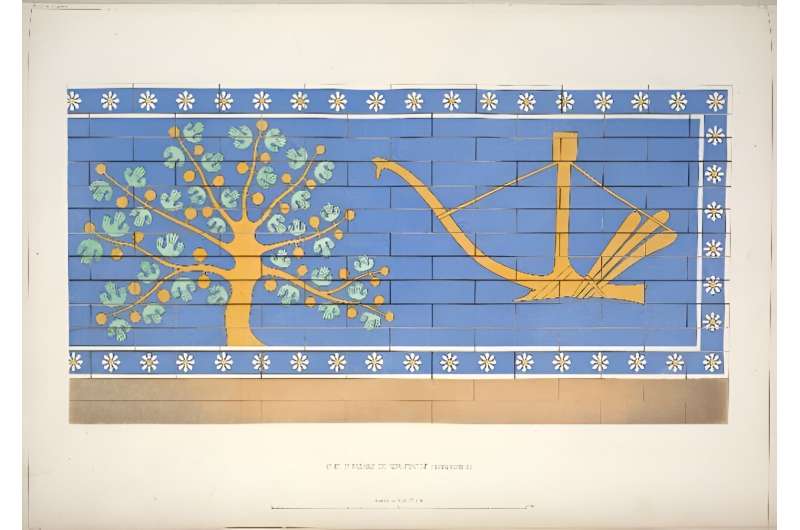

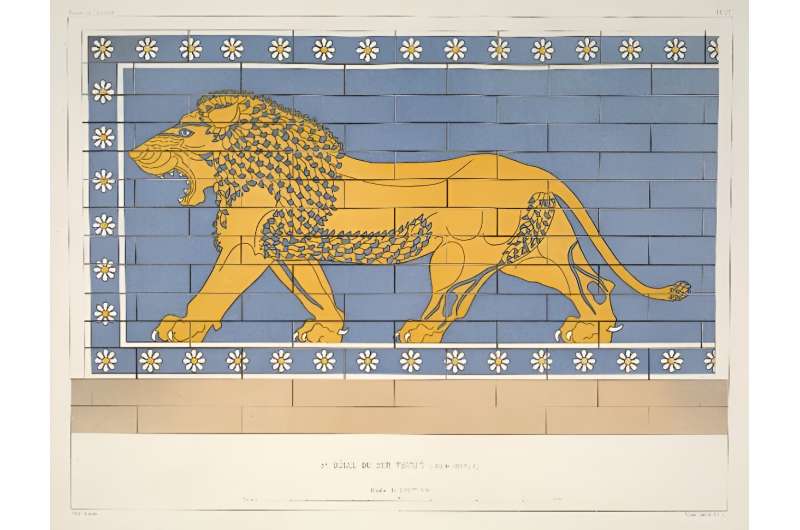

The sequence of five symbols—a lion, eagle, bull, fig tree and plow—was first made known to the modern world through drawings published by French excavators in the late nineteenth century. Since then, there has been a spate of ideas about what the symbols might mean.

They have been compared to Egyptian hieroglyphs, understood as reflections of imperial might, and suspected to represent the king’s name—but how?

Dr. Martin Worthington of Trinity’s School of Languages, Literatures and Cultural Studies has proposed a new solution in a paper published April 26 in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. He argues the Assyrian words for the five symbols (lion, eagle, bull, fig tree and plow) contain, in the right sequence, the sounds that spell out the Assyrian form of the name “Sargon” (šargīnu).

Late 19th century drawings of the tree and plough symbols published by French excavator Victor Place. © New York Public Library

Sometimes, the same archaeological site uses only three of the symbols (lion, tree, plow), which Dr. Worthington argues again write the name “Sargon,” following similar principles.

Dr. Worthington commented, “The study of ancient languages and cultures is full of puzzles of all shapes and sizes, but it’s not often in the Ancient Near East that one faces mystery symbols on a temple wall.”

What is more, according to Dr. Worthington, each of the five symbols can also be understood as a constellation. Thus, the lion represents Leo, and the eagle Aquila (our own constellations are largely inherited from Mesopotamia, via the Greeks, so many of them are the same). The fig tree stands in for the hard-to-illustrate constellation “the Jaw” (which we don’t have today), on the basis that iṣu “tree” sounds similar to isu “jaw.”

“The effect of the five symbols, was to place Sargon’s name in the heavens, for all eternity—a clever way to make the king’s name immortal. And, of course, the idea of bombastic individuals writing their name on buildings is not unique to ancient Assyria,” says Dr. Worthington.

Late 19th century drawings of the lion symbol published by French excavator Victor Place. © New York Public Library

Ancient Mesopotamia, or modern Iraq and neighboring regions, was home to Babylonians, Assyrians, Sumerians, and others, and is today being researched from cuneiform writings, which survive in abundance. Indeed, writing was probably invented there around 3400 BC. So, though Sargon’s scholars would not have been aware of this, in devising new written symbols they were echoing Mesopotamian history from over a thousand years before.

Dr. Worthington explained, “I can’t prove my theory, but the fact it works for both the five-symbol sequence and the three-symbol sequence, and that the symbols can also be understood as culturally appropriate constellations, strikes me as highly suggestive. The odds against it all being happenstance are—forgive the pun—astronomical.”

Dr. Worthington specializes in the languages and civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, including those of the Babylonians, Assyrians and Sumerians.

“This region of the world, which includes present-day Iraq and parts of Iran, Turkey and Syria, is often referred to as the “cradle of civilization.” It is where cities and empires were born, and its story is a huge part of human history.

It is because of the Mesopotamian habit of counting in sixties that today we have 60 minutes in an hour, and Abraham (a central figure in three of the world’s major religions) is said to have come from the Mesopotamian city of Ur.

“Solving puzzles (or trying to) is an especially fun bit,” says Dr. Worthington, “but Mesopotamian studies at large have the grander aim of understanding the complexity and diversity of a huge part of human societies and cultural achievements.”

More information:

Martin Worthington, Solving the Starry Symbols of Sargon II, Bulletin of the American Society of Overseas Research (2024). DOI: 10.1086/730377

Provided by

Trinity College Dublin

Citation:

Assyriologist claims to have solved archaeological mystery from 700 BC (2024, May 3)