In the Middle Ages, alchemists were notoriously secretive and didn’t share their knowledge with others. Danish Tycho Brahe was no exception. Consequently, we don’t know precisely what he did in the alchemical laboratory located beneath his combined residence and observatory, Uraniborg, on the now Swedish island of Ven.

Only a few of his alchemical recipes have survived, and today, there are very few remnants of his laboratory. Uraniborg was demolished after his death in 1601, and the building materials were scattered for reuse.

However, during an excavation in 1988–1990, some pottery and glass shards were found in Uraniborg’s old garden. These shards were believed to originate from the basement’s alchemical laboratory. Five of these shards—four glass and one ceramic—have now undergone chemical analyses to determine which elements the original glass and ceramic containers came into contact with.

The chemical analyses were conducted by Professor Emeritus and expert in archaeometry, Kaare Lund Rasmussen from the Department of Physics, Chemistry, and Pharmacy, University of Southern Denmark. Senior researcher and museum curator Poul Grinder-Hansen from the National Museum of Denmark oversaw the insertion of the analyses into historical context.

Enriched levels of trace elements were found on four of them, while one glass shard showed no specific enrichments. The study has been published in the journal Heritage Science.

“Most intriguing are the elements found in higher concentrations than expected—indicating enrichment and providing insight into the substances used in Tycho Brahe’s alchemical laboratory,” said Lund Rasmussen.

The enriched elements are nickel, copper, zinc, tin, antimony, tungsten, gold, mercury, and lead, and they have been found on either the inside or outside of the shards.

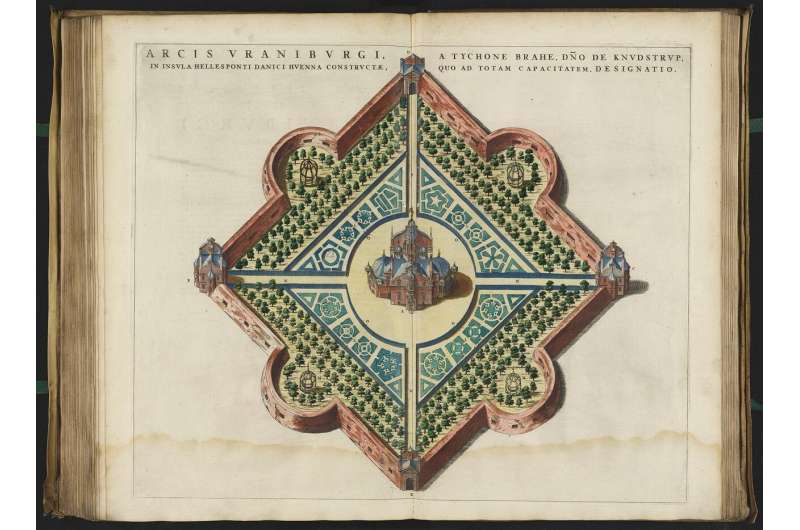

The building Uraniborg on the island of Ven (now Sweden) was a combined observatory, laboratory and residence for Danish renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe. © wikipedia

Most of them are not surprising for an alchemist’s laboratory. Gold and mercury were—at least among the upper echelons of society—commonly known and used against a wide range of diseases.

“But tungsten is very mysterious. Tungsten had not even been described at that time, so what should we infer from its presence on a shard from Tycho Brahe’s alchemy workshop?” said Lund Rasmussen.

Tungsten was first described and produced in pure form more than 180 years later by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Tungsten occurs naturally in certain minerals, and perhaps the element found its way to Tycho Brahe’s laboratory through one of these minerals. In the laboratory, the mineral might have undergone some processing that separated the tungsten, without Tycho Brahe ever realizing it.

However, there is also another possibility that Professor Lund Rasmussen emphasizes has no evidence whatsoever—but which could be plausible.

Already in the first half of the 1500s, the German mineralogist Georgius Agricola described something strange in tin ore from Saxony, which caused problems when he tried to smelt tin. Agricola called this strange substance in the tin ore “Wolfram” (German for Wolf’s froth, later renamed to tungsten in English).

“Maybe Tycho Brahe had heard about this and thus knew of tungsten’s existence. But this is not something we know or can say based on the analyses I have done. It is merely a possible theoretical explanation for why we find tungsten in the samples,” said Lund Rasmussen.

Tycho Brahe belonged to the branch of alchemists who, inspired by the German physician Paracelsus, tried to develop medicine for various diseases of the time: plague, syphilis, leprosy, fever, stomach aches, etc. But he distanced himself from the branch that tried to create gold from less valuable minerals and metals.

Tycho Brahe receives Jacob VI of Scotland at Uraniborg,. © Royal Library, Denmark

In line with the other medical alchemists of the time, he kept his recipes close to his chest and shared them only with a few selected individuals, such as his patron, Emperor Rudolph II, who allegedly received Tycho Brahe’s prescriptions for plague medicine.

We know that Tycho Brahe’s plague medicine was complicated to produce. It contained theriac, which was one of the standard remedies for almost everything at the time and could have up to 60 ingredients, including snake flesh and opium. It also contained copper or iron vitriol (sulfates), various oils, and herbs.

After various filtrations and distillations, the first of Brahe’s three recipes against plague was obtained. This could be made even more potent by adding tinctures of, for example, coral, sapphires, hyacinths, or potable gold.

“It may seem strange that Tycho Brahe was involved in both astronomy and alchemy, but when one understands his worldview, it makes sense. He believed that there were obvious connections between the heavenly bodies, earthly substances, and the body’s organs,” explained Grinder-Hansen.

“Thus, the sun, gold, and the heart were connected, and the same applied to the moon, silver, and the brain; Jupiter, tin, and the liver; Venus, copper, and the kidneys; Saturn, lead, and the spleen; Mars, iron, and the gallbladder; and Mercury, mercury, and the lungs. Minerals and gemstones could also be linked to this system, so emeralds, for example, belonged to Mercury.”

Lund Rasmussen has previously analyzed hair and bones from Tycho Brahe and found, among other elements, gold. This could indicate that Tycho Brahe himself had taken medicine that contained potable gold.

More information:

Kaare Lund Rasmussen, Chemical analysis of fragments of glass and ceramic ware from Tycho Brahe’s laboratory at Uraniborg on the island of Ven (Sweden), Heritage Science (2024).

Provided by

University of Southern Denmark

Citation:

Chemical analyses find hidden elements from renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe’s alchemy laboratory (2024, July 24)