The ability to cooperate plays a crucial role in many areas of human life—whether in the workplace, in politics, or in personal relationships. A new study shows how memory and the recollection of past behavior can influence the willingness to cooperate. This insight is particularly relevant for shaping social and economic systems where trust and cooperation are central.

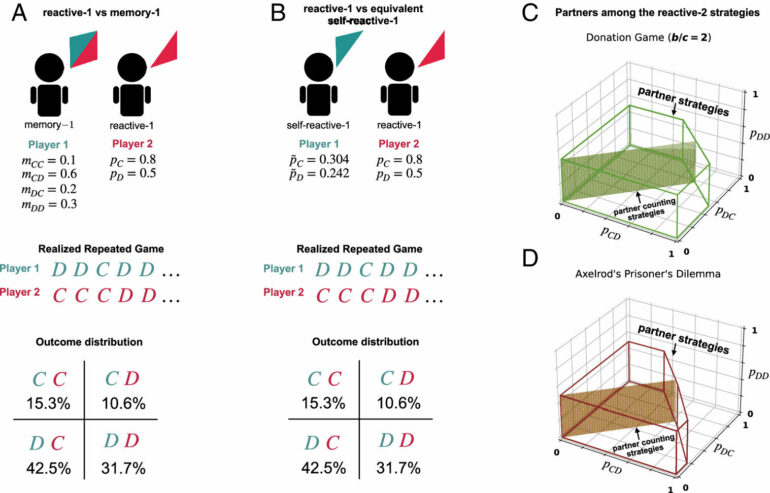

In many social interactions, we operate based on the principle of “direct reciprocity”—we help others because we expect them to help us when we need it. Traditionally, cooperation has been explained using simple strategies that only consider the most recent behavior. These so-called memory-1 strategies, which only consider the last action of a co-player, have long dominated scientific research.

However, in real-world social situations—such as in workgroups, among politicians, or in interpersonal relationships—past actions often also play a role. Especially in complex and error-prone environments, people tend to rely on more “memory” to make decisions.

The recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences explores how longer-term memory in social interactions can lead to better cooperation. The researchers focused on so-called “reactive-n strategies,” which are based on the co-player’s actions over several previous rounds.

They found that strategies that take more past behavior into account can stabilize cooperation and promote it in the long term. These results have important implications for our understanding of cooperation in society: they show that a long-term perspective on others’ behavior—the “memory” of past cooperation or conflicts—can enable stable collaboration.

These findings are especially important in dynamic social environments, where mistakes and misunderstandings frequently occur. They explain why, in groups where long-term relationships matter (such as in teams or political partnerships), the willingness to cooperate increases when the entire history of collaboration is considered. For businesses and organizations, this might mean fostering a culture of trust and long-term collaboration, where mistakes do not immediately lead to the breakdown of cooperation.

Overall, the latest findings show that memory plays a key role in promoting cooperation—not only in theoretical models but also in everyday life and the design of social systems. They offer a new perspective on how long-term collaboration can be successfully structured in a world often shaped by short-term interests and mistakes.

More information:

Nikoleta E. Glynatsi et al, Conditional cooperation with longer memory, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2420125121

Provided by

Max Planck Society

Citation:

Cooperation in society: How our memory influences our behavior (2024, December 9)