Archaeologists from Tel Aviv University and the National Museum in Copenhagen have analyzed 450 pottery vessels made in Tel Hama, a town at the edge of the Ebla Kingdom, one of the most important Syrian kingdoms in the Early Bronze Age (about 4,500 years ago).

They found that two-thirds of the pottery vessels were made by children—starting at the ages of 7 and 8. Along with children’s use for the kingdom’s needs, they also found evidence of the children’s independent creations outside the industrial framework, illustrating the spark of childhood even in early urban societies.

The research was led by Dr. Akiva Sanders, a Dan David Fellow at the Entin Faculty of Humanities, Tel Aviv University. The findings were published in the journal Childhood in the Past.

Dr. Sanders states, “Our research allows us a rare glimpse into the lives of children who lived in the area of the Ebla Kingdom, one of the oldest kingdoms in the world. We discovered that at its peak, roughly from 2400 to 2000 BCE, the cities associated with the kingdom began to rely on child labor for the industrial production of pottery.

“The children worked in workshops starting at the age of 7, and were specially trained to create cups as uniformly as possible—which were used in the kingdom in everyday life and at royal banquets.”

As is well known, a person’s fingerprints do not change throughout their life. For this reason, the size of the palm can be roughly deduced by measuring the density of the margins of the fingerprint—and from the size of the palm, the age and sex of the person can be estimated.

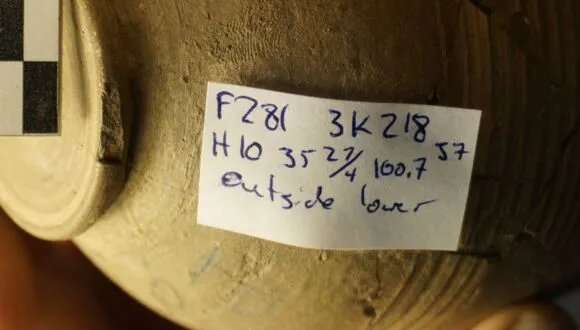

Pottery vessel made in Tel Hama. © Tel-Aviv University

The pottery from Tel Hama, on the southern border of the Kingdom of Ebla, was excavated in the 1930s, and since then has been kept in the National Museum in Denmark. From the analysis of the fingerprints in the pottery, it appears that most of them were made by children. In the city of Hama city, two-thirds of the pottery was made by children. The other third was created by older men.

“At the beginning of the Early Bronze Age, some of the world’s first city-kingdoms arose in the Levant and Mesopotamia,” says Dr. Sanders. “We wanted to use the fingerprints on the pottery to understand how processes such as urbanization and the centralization of government functions affected the demographics of the ceramic industry.

“In the town of Hama, an ancient center for the production of ceramics, we initially see potters around the age of 12 and 13, with half the potters being under 18, and with boys and girls in equal proportions.

“This statistic changed with the formation of the Kingdom of Ebla when we saw that potters started to produce more goblets for banquets. And since more and more alcohol-fueled feasts were held, the cups were frequently broken—and therefore more cups needed to be made.

“Not only did the Kingdom begin to rely more and more on child labor, but the children were trained to make the cups as similar as possible. This is a phenomenon we also see in the Industrial Revolution in Europe and America: It is very easy to control children and teach them specific movements to create standardization in handicrafts.”

However, there was one bright spot in the children’s lives: making tiny figurines and miniature vessels for themselves. “These children taught each other to make miniature figurines and vessels, without the involvement of the adults,” says Dr. Sanders.

“It is safe to say that they were created by children—and probably including those skilled children from the cup-making workshops. It seems that in these figurines the children expressed their creativity and their imagination.”

More information:

Akiva Sanders, Child and Clay: Fingerprints of a Dual Engagement at Hama, Syria, Childhood in the Past (2024). DOI: 10.1080/17585716.2024.2380137

Provided by

Tel-Aviv University

Citation:

Did child labor fuel the ancient pottery industry? (2024, October 15)