To reach the only place in the world where cave paintings of prehistoric marine life have been found, archaeologists have to dive to the bottom of the Mediterranean off southern France.

Then they have to negotiate a 137-meter (yard) natural tunnel into the rock, passing through the mouth of the cave until they emerge into a huge cavern, much of it now submerged.

Three men died trying to discover this “underwater Lascaux” as rumors spread of a cave to match the one in southwestern France that completely changed the way we see our Stone Age ancestors.

Lascaux—which Picasso visited in 1940—proved the urge to make art is as old as humanity itself.

Archaeologist Luc Vanrell’s life changed the second he surfaced inside the Cosquer cavern and saw its staggering images. Even now, 30 years on, he remembers the “aesthetic shock”.

But the cave and its treasures, some dating back more than 30,000 years, are in grave danger. Climate change and water and plastic pollution are threatening to wash away the art prehistoric men and women created over 15 millennia.

Since a sudden 12-centimeter (near-five-inch) rise in the sea level there in 2011, Vanrell and his colleagues have been in a race against time to record everything they can.

Every year the high water mark rises a few more millimeters, eating away a little more of the ancient paintings and carvings.

Prehistoric wonders

Vanrell and the diver-archaeologists he leads are having to work faster and faster to explore the last corners of the 2,500 square meter (27,000 square feet) grotto to preserve a trace of its neolithic wonders before they are lost.

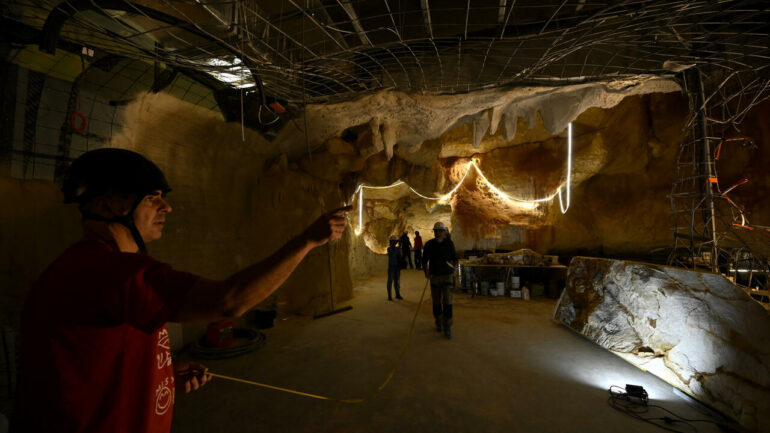

An almost life-sized recreation of the Cosquer cavern will open this week a few kilometers (miles) away in Marseille.

AFP joined the dive team earlier this year as they raced to finish the digital mapping for a 3D reconstruction of the cave.

Around 600 signs, images and carvings—some of aquatic life never before seen in cave paintings—have been found on the walls of the immense cave 37 meters below the azure waters of the breathtaking Calanques inlets east of Marseille.

“We fantasized about bringing the cave to the surface,” said diver Bertrand Chazaly, who is in charge of the operation to digitalise the cave.

“When it is finished, our virtual Cosquer cavern—which is accurate to within millimeters—will be indispensable for researchers and archaeologists who will not be able to physically get inside.”

Children’s hands

The cave was some “10 kilometers from the coast” when it was in use, archaeologist Michel Olive told AFP. “At the time we were in the middle of an ice age and the sea was 135 meters lower” than it is today.

From the dive boat, Olive, who is in charge of studying the cave, draws with his finger a vast plain where the Mediterranean now is. “The entrance to the cave was on a little promontory facing south over grassland protected by cliffs. It was an extremely good place for prehistoric man,” he said.

The walls of the cave show the coastal plain was teeming with wildlife—horses, deer, bison, ibex, prehistoric auroch cows, saiga antelopes but also seals, penguins, fish and a cat and a bear.

The 229 figures depicted on the walls cover 13 different species.

But neolithic men and women also left a mark of themselves on the walls, with 69 red or black hand prints as well as three left by mistake, including by children.

And that does not count the hundreds of geometric signs and the eight sexual depictions of male and female body parts.

What also stands out about the cave is the length of time it was occupied, said Vanrell, “from 33,000 to 18,500 years ago”.

The sheer density of its graphics puts “Cosquer among the four biggest cave art sites in the world alongside Lascaux, Altamira in Spain and Chauvet,” which is also in southern France.

“And because the cave walls that are today underwater were probably also once decorated, nothing else in Europe compares to its size,” he added.

Exploring Cosquer is also “addictive”, the 62-year-old insisted, with a twinkle in his eye. “Some people who have been working on the site get depressed if they haven’t been down in a while. They miss their favorite bison,” he smiled.

For Vanrell, diving down is like a “journey into oneself”. The spirit “of the place seeps into you”.

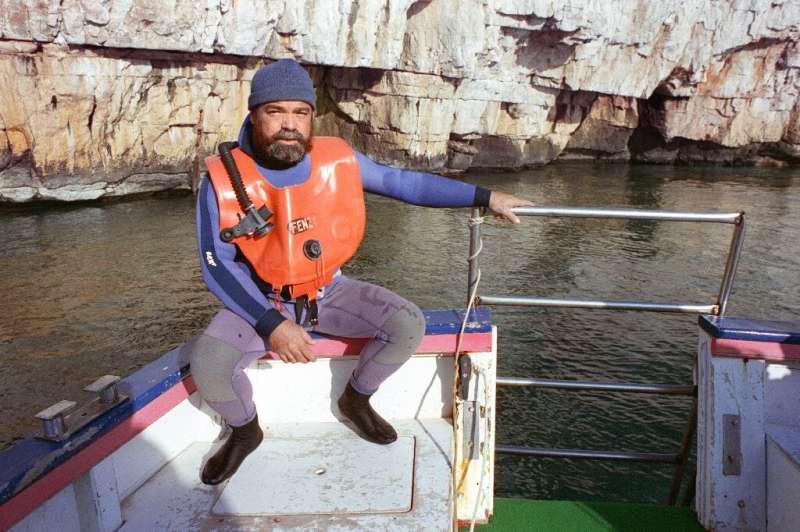

Henri Cosquer, the diver who found the cave, photographed on a boat above the entrance in 1991.

Discovery and death

Henri Cosquer, a professional deep sea diver running a diving school, said he found the cave by chance in 1985, just 15 meters off the bare limestone cliffs.

Little by little he dared to venture further and further into 137-meter-long breach in the cliff until one day he came out through a cavity cut out by the sea.

“I came up in a pitch-dark cave. You are soaking, you come out of the mud and you slide around… It took me a few trips to go right around it,” he told AFP.

“At the start, I saw nothing with my lamp and then I came across a hand print,” the diver said.

While the law dictates that such discoveries must be declared immediately to the authorities so they can be preserved, Cosquer kept the news to himself and a few close friends.

“Nobody owned the cave. When you find a good spot for mushrooms, you don’t tell everyone about it, do you?” he said.

But rumors of this aquatic Lascaux drew other divers and three died in the tunnel leading to the cave. Marked by the tragedies, Cosquer owned up to his discovery in 1991. The cave which bears his name is now sealed off by a railing. Only scientific teams are allowed inside.

Dozens of archeological research missions have been carried out since to study and preserve the site and make an inventory of the paintings and carvings. But resources began to drain away when Chauvet, which is much easier to access, was discovered in the Ardeche region in 1994.

Climate change damage

Only in 2011 did things begin to change when Olive and Vanrell raised the alarm after the rapid rise in the sea level led to irreparable damage to some images.

“It was a catastrophe, and it really shook us psychologically,” Vanrell recalled, particularly the enormous damage to the horse drawings.

“All the data shows that the sea level is rising faster and faster,” said geologist Stephanie Touron, a specialist in prehistoric painted caves at France’s historic monuments research laboratory.

“The sea rises and falls in the cavity with variations in climate, washing the walls and leeching out soil and materials that are rich in information,” she said.

Microplastic pollution is making the damage to the paintings even worse.

In the face of such an existential threat, the French government has launched a major push to record everything about the cavern, with archaeologist Cyril Montoya tasked with trying to better understand the prehistoric communities who used it.

Mysteries

One of the mysteries he and his team will try to solve will be the trace of cloth on the cave wall, which might confirm a theory that hunter gatherers were making clothes at the time when the cave was occupied.

Images of the horses with long manes also raises another major question. Vanrell suspects this might indicate that they may have been already domesticated, at least partly, since wild horses have shorter manes, shorn down by galloping through bushes and vegetation. A drawing of what might be a harness may back up his theory.

Areas preserved under a layer of translucent calcite also show the “remains of coal”, Montoya believes, which could have been used for painting or for heating or lighting. They may even have burned the coal on top of stalagmites, turning them into “lamps to light the cavern”.

But the central question of what the cave was used for remains an enigma, Olive admitted.

While archaeologists agree that people did not live there, Olive said some believe it was a “sanctuary, or a meeting place, or somewhere they mined moonmilk, the white substance on (limestone) cave walls that was used for body paint and for the background for paintings and carving.”

Replica

The idea of making a replica of the site was first mooted soon after the cave was discovered. But it wasn’t until 2016 that the regional government decided that it would be in a renovated modern building in Marseille next to Mucem, the museum of European and Mediterranean civilisations at the mouth of the city’s Old Port.

Using the 3D data gathered by the archaeological teams, the 23-million-euro ($24-million) replica is slightly smaller than the original cave but includes copies of all the paintings and 90 percent of the carvings, said Laurent Delbos from Klebert Rossillon, the company which copied the Chauvet cave in 2015.

Artist Gilles Tosello is one of the craftspeople who has been copying the paintings using the same charcoal and tools that his Stone Age forerunners used.

“The prehistoric artists wrote the score long ago and now I am playing it,” he said sitting in the dark in his studio, a detail of a horse lit up before him on the recreated cave wall.

Clearly moved, he hailed the great mastery and “spontaneity” of his prehistoric predecessors, whose confident brush strokes clearly came from “great knowledge and experience. That liberty of gesture and sureness never ceases to amaze me,” he said.

2022 AFP

Citation:

Race to save undersea Stone Age cave art masterpieces (2022, May 30)