Looks like Kamala Harris’ campaign is getting it right when it comes to social media, according to a new study. As democrats are playing up their sunny outlook in their presidential campaign, a study published in Scientific Reports suggests that emphasizing in-party positive messaging is more effective for political communication on social media than promoting out-party hostility.

“We found that hateful content does not spread as much as positive content,” says Samuel Martin-Gutierrez from the Complexity Science Hub. “Our results are consistent with recent findings showing that hateful and negative polarizing content is not as shared and amplified as we thought it would be,” adds Martin-Gutierrez.

Elections: A key moment

In this study, Martin-Gutierrez worked with other complexity scientists, as well as a sociologist and a political scientist, to analyze Twitter activity during four consecutive election campaigns in Spain, from 2015 to 2019. They focused on the evolving nature of partisan interactions on Twitter, particularly in response to the rise of the Spanish radical right-wing party, Vox.

According to the authors of the study, elections are a key moment. As elections approach, political competition manifests a visible influence on individual levels of polarization. In addition, parties and candidates “tend to behave strategically in their use of and presence on social media at this time.”

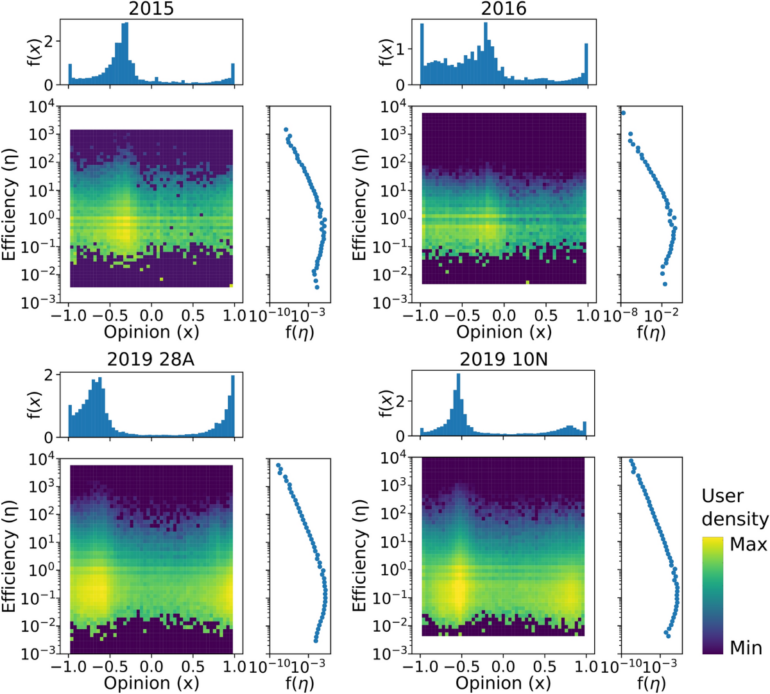

The results pointed out a notable trend: users affiliated with mainstream political parties were more likely to retweet content that reinforced their party affiliation, thereby creating high-efficiency epistemic bubbles. These bubbles were characterized by consistent sharing of positive messages within the party, which garnered higher retweet rates and suggested strong internal cohesion, according to the authors.

In contrast, the study found that efforts to spread out-party hostility—content aimed at opposing parties—resulted in lower engagement levels, even among supporters of more radical political parties. Martin-Gutierrez and his colleagues argue that, while the presence of out-party hostility does contribute to the formation of exclusionary echo chambers, these are marked by low communication efficiency, as evidenced by fewer retweets.

“Our study suggests that emphasizing in-party positive messaging works better on social media for political communication,” says Martin-Gutierrez. “This approach not only fosters a more cohesive and supportive online community but also counters the negative effect of out-party hostility, which tends to drive moderate users away and decrease overall engagement.”

These findings have significant implications for political communication strategies, suggesting that parties and candidates might benefit more from focusing on positive, affirming messages rather than engaging in hostile rhetoric. “If you want to spread a message on social media, it seems to be more efficient to focus on positive content,” says Martin-Gutierrez. Also, this approach could promote a less toxic online environment and a more constructive political dialogue.

Epistemic bubbles and echo chambers

In the era of social media, fake news, and polarization, these two terms became popular among scholars. In any case, you probably saw them in the news: epistemic bubbles and echo chambers. C. Thi Nguyen, a philosophy professor at Utah Valley University, explains the differences between echo chambers and epistemic bubbles in an essay on Aeon. Thi Nguyen says, “An epistemic bubble is when you don’t hear people from the other side. An echo chamber is what happens when you don’t trust people from the other side.”

In an epistemic bubble, people are only exposed to information that aligns with their existing beliefs. In that sense, people tend to be missing out on other perspectives because they aren’t even noticed or considered. It is possible that people are selectively avoiding contact with others who hold opposing views—”…we like to engage in selective exposure, seeking out information that confirms our own worldview,” according to Thi Nguyen.

But it is also possible that an omission was entirely unintentional. Though people may not actively try to avoid disagreement, their X—former Twitter—feed tends to be similar to their own.

In an echo chamber, other relevant voices have been actively excluded and discredited. It tends to isolate its members by actively alienating them from any outside sources. “Where an epistemic bubble merely omits contrary views, an echo chamber brings its members to actively distrust outsiders,” explains Thi Nguyen. According to the philosophy professor, examples of echo chambers include anti-vaccination, breastfeeding, Paleo diet, and CrossFit exercise.

More information:

Samuel Martin-Gutierrez et al, In-party love spreads more efficiently than out-party hate in online communities, Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-65688-9

Provided by

Complexity Science Hub Vienna

Citation:

Spread the love (online): Study reveals in-party positivity drives online engagement more than out-party hostility (2024, August 19)