Scientists’ careers are defined by their contributions to the peer-reviewed literature. Yet, a study just out in Nature Ecology & Evolution by Michigan State University researchers reveals that peer review disadvantages some scientists more than others, but solutions to rectify this disparity remain elusive.

Despite ever increasing cries for greater diversity, equity, and inclusion in science, the peer reviewed literature remains largely dominated by a handful of groups such as male authors from the United States and United Kingdom. While the causes for this are multifaceted, the role that bias in peer review plays has remained controversial.

MSU researchers analyzed data from more than 300,000 biological science manuscripts to see if the authors’ demographics mattered when it came to deciding if research was worthy of publication.

Their conclusions: Authors from historically excluded groups generally face worse peer review outcomes; few studies have examined how well interventions address peer review bias; and journals aren’t doing much to ensure an equitable review process.

“We were inspired to conduct the study after observing explicitly biased comments as co-authors and co-reviewers and experiencing seemingly worse peer review outcomes compared to colleagues that do not identify as members of historically excluded groups,” said Olivia Smith, the study’s lead author who is an MSU Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior (EEB) Program Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow.

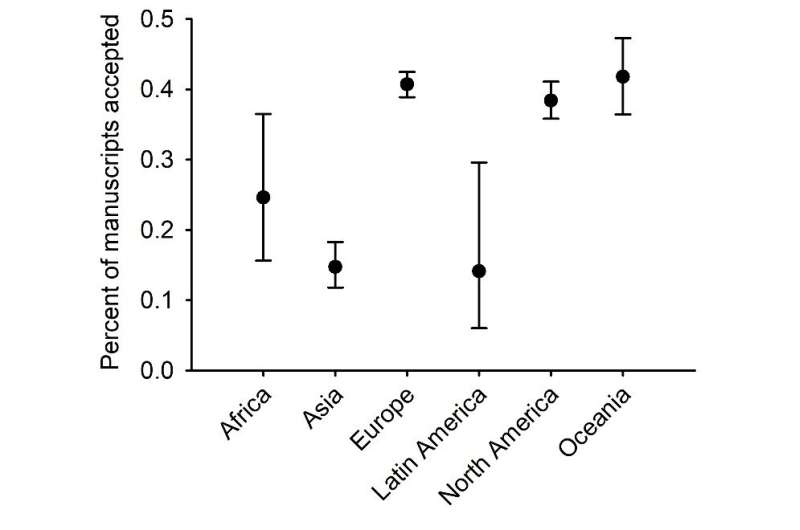

The study analyzed data collected from 31 prior studies to look for evidence of bias due to author demographics. The study found lower overall acceptance rates for authors who were affiliated with institutions in Asia, whose country’s primary language was not English and were in countries with relatively low measures of social and economic development. Authors’ assumed gender also was linked to worse review outcomes.

The study looked for solutions to reduce bias and found few studies given the wide disparities they uncovered in the review system. The team only uncovered data on how diversity of reviewers and editorial boards and double-blind review—where the authors and reviewers remain anonymous to each other throughout the review process—impact review outcomes.

The study found lower overall acceptance rates for authors affiliated with institutions in Asia, whose country’s primary language was not English and who were in countries with relatively low measures of social and economic development. © Michigan State University Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior Program

“Academics often self-identify as progressive and profoundly opposed to ethnic and gender discrimination. However, as a community we have been extremely reticent to make the effort to introduce double-blind peer review,” said Tom Tregenza, professor of evolutionary ecology at the University of Exeter. Tregenza was not involved in the study and has published research on the peer review process. “With Smith et al.’s study the jury is in—single blind peer review is discriminatory and we’re not doing enough about it.

“Double blind review is far from perfect, but do we need another million data points to convince us that we can’t just keep limping on with a review system that assumes scientists are not subject to the biases that are so well established by their own research.”

The authors also examined policies that journals have in place for the peer review process including what peer review models are being used and specific review guidelines for authors and reviewers, particularly around inflammatory comments towards authors for whom English is not a primary language. They found that journals aren’t really doing much to mitigate potential bias. For example, less than 16% of journals in ecology and evolutionary biology were using a double-blind review model. Further, only 2% had guidelines for peer reviewers that explicitly mentioned social justice issues.

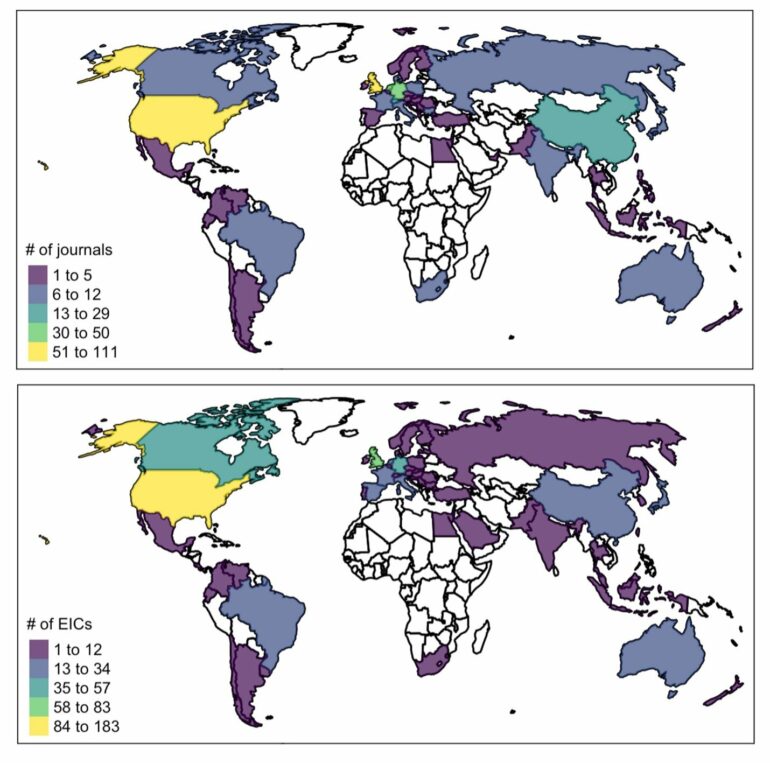

Smith and colleagues further traced the locations of the journals and their editors-in-chief and found them to be concentrated in just a few parts of the world—the same ones with the best outcomes in peer review.

With that said, the authors acknowledge their study’s limitations including the fact that it is difficult to tell if a manuscript is rejected because of bias, or because the work did not meet a journals’ standards.

Whether it is truly bias or disparate outcomes due to other factors, the study clearly shows that across hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, author demographics are a strong predictor of success in peer review—and that the system needs to change.

“Peer review is a central part of the scientific process and key to the advancement of scientists’ careers,” Smith said. “We hope our synthesis will prompt future studies to swiftly and fully document the extent of bias and identify effective solutions. We also hope that it will be a driving force for journals to adopt stronger policies for an equitable peer review system.”

Besides Smith, the paper is authored by MSU-EEB scholars Kayla Davis, Riley Pizza, Robin Waterman, Kara Dobson, Brianna Foster, Julie Jarvey, Leonard Jones, Wendy Leuenberger, Nan Nourn, Emily Conway, Cynthia Fiser, Zoe Hansen, Ani Hristova, Caitlin Mack, Alyssa Saunders, Olivia Utley, Moriah Young, and Courtney Davis.

More information:

Olivia Smith, Peer review perpetuates barriers for historically excluded groups, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-023-01999-w. www.nature.com/articles/s41559-023-01999-w

Provided by

Michigan State University

Citation:

Study reveals inequity in journal peer review (2023, March 13)