Conservative voters have slightly larger amygdalas than progressive voters—by about the size of a sesame seed. In a replication study published September 19 in the journal iScience, researchers revisited the idea that progressive and conservative voters have identifiable differences in brain morphology, but with a 10x larger and more diverse sample size than the original study.

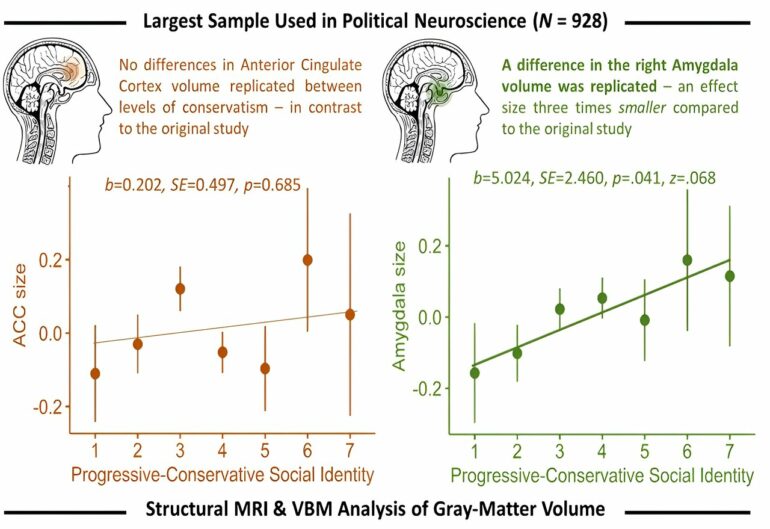

Their results confirmed that the size of a person’s amygdala is associated with their political views but failed to find a consistent association between politics and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).

Anatomical differences in both the amygdala and ACC varied depending on a person’s economic and social ideology—which aren’t necessarily aligned—indicating that relationships between political ideology and brain structure are nuanced and multidimensional.

“It was really a surprise that we replicated the amygdala finding,” says first author and political psychology and neuroscience researcher Diamantis Petropoulos Petalas of The American College of Greece and member of the @HotPoliticsLab at the University of Amsterdam. “Quite honestly, we did not expect to replicate any of these findings.”

The new study, which aimed to replicate a widely shared 2011 study that was based on 90 UK university students, used pre-existing MRI brain scans from 928 individuals aged 19-26 whose levels of education and political identities were representative of the Dutch population.

Because the Netherlands has a multi-party political system, the study was also able to compare brain structures along the continuum from left- to rightwing, in contrast to the two-party UK system. In addition, the researchers looked at the participants’ “ideology” from various angles, including their political identity and stance on socioeconomic issues, which allowed them to compare brain structures along different dimensions of progressivism and conservativism.

The researchers paired the brain data with a questionnaire about the participants’ politics, which included questions about their social and economic identity (e.g., how they view themselves on a sliding scale of progressive to conservative, and which political party they identify with), and questions pertaining to their social and economic ideology (e.g., where they stand on different social and economic issues, such as women’s and LGBQT rights, income inequality, and profit sharing).

“We see ideology as a complex, multidimensional product that includes different attitudes on social and economic matters, as well as identification with progressive or conservative ideals; it’s really not just about the left or the right,” says Petropoulos.

In agreement with the original study, the researchers found an association between conservatism and the volume of gray matter in the amygdala; however, this association was three times weaker compared to the original study.

“The amygdala controls the perception and the understanding of threats and risk uncertainty, so it makes a lot of sense that individuals who are more sensitive towards these issues have higher needs for security, which is something that typically aligns with more conservative ideas in politics,” says Petropoulos.

The association between amygdala size and conservatism also depended on the political party that the individual identified with—for example, participants who identified with the socialist party, which has radically left-wing economic policies but more conservative social values, had on average more gray matter in the amygdala compared to other progressive parties.

“The Netherlands has a multi-party system, with different parties representing a spectrum of ideologies, and we find a very nice positive correlation between the parties’ political ideology and the amygdala size of that person,” says Petropoulos.

“That speaks to the idea that we’re not talking about a dichotomous representation of ideology in the brain, such as Republicans versus Democrats as in the US, but we see a more fine-grained spectrum of how political ideology can be reflected in the brain’s anatomy.”

However, in contrast to the original study, the team did not find any association between conservatism and a smaller volume of gray matter in the ACC, a brain region involved in error detection, impulse control, and emotional regulation.

The researchers also extended their analysis to examine potential associations between political identity and other regions of the brain. This analysis uncovered a positive association between the gray matter volume in the right fusiform gyrus, a region in the temporal lobe that is essential for visual and cognitive functions, and economic and social conservatism.

“These regions have to do with facial recognition, so it makes sense that they might be involved when one is thinking about political issues, because political issues often remind us of the political personas that represent ideology on those issues,” says Petropoulos. “Just the memory of the face of a politician, for instance, might make the fusiform gyrus light up a little.”

The MRI scans used in this study provide information only on the anatomy of different brain regions, but the researchers say that future work should integrate information about the functional connections between the amygdala and different parts of the brain.

“I think the future of this endeavor to identify political orientations in the brain will be to look more towards functional connectivity network and neural synchrony studies—how brain networks organize and synchronize between individuals, and whether there are differences in this synchronization when individuals with different political ideologies consume similar content,” says Petropoulos.

More information:

Diamantis Petropoulos Petalas et al, Is Political Ideology Correlated with Brain Structure? A Preregistered Replication, iScience (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110532. www.cell.com/iscience/fulltext … 2589-0042(24)01757-7

Citation:

Study suggests political ideology is associated with differences in brain structure, but less so than previously thought (2024, September 19)