More than 200 years after Napoleon met defeat at Waterloo, the bones of soldiers killed on that famous battlefield continue to intrigue Belgian researchers and experts, who use them to peer back to that moment in history.

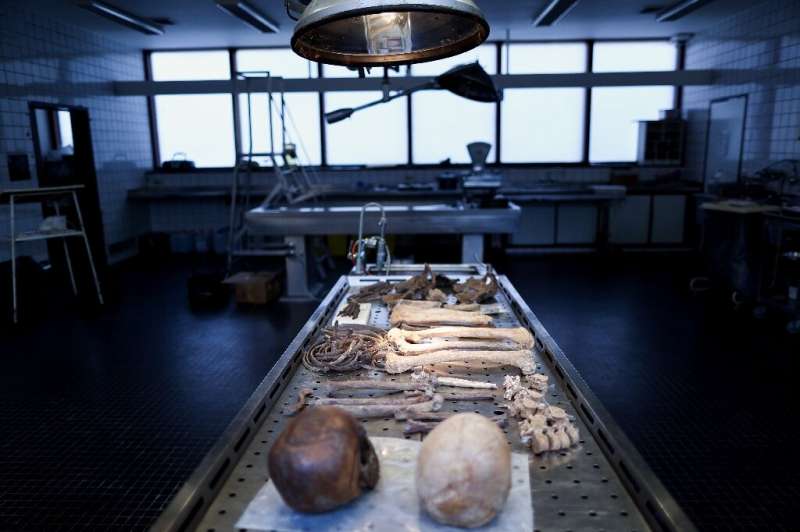

“So many bones—it’s really unique!” exclaimed one such historian, Bernard Wilkin, as he stood in front of a forensic pathologist’s table holding two skulls, three femurs and hip bones.

He was in an autopsy room in the Forensic Medicine Institute in Liege, eastern Belgium, where tests are being carried out on the skeletal remains to determine from which regions the four soldiers they belong to came from.

That in itself is a challenge.

Half a dozen European nationalities were represented in the military ranks at the Battle of Waterloo, located 20 kilometers (12 miles) south of Brussels.

That armed clash of June 18, 1815 ended Napoleon Bonaparte’s ambitions of conquering Europe to build a great empire, and resulted in the deaths of around 20,000 soldiers.

The battle has since been pored over by historians, and—with advances in the genetic, medical and scanning fields—researchers can now piece together pages of the past from the remains buried in the ground.

Some of those remains have been recovered through archeological digs, such as one last year that allowed the reconstitution of a skeleton found not far from a field hospital the British Duke of Wellington had set up.

But the remains examined by Wilkin surfaced through another route.

Some of those remains have been recovered through archeological digs.

‘Prussians in my attic’

The historian, who works for the Belgian government’s historical archives, said he gave a conference late last year and “this middle-aged man came to see afterwards and told me, ‘Mr. Wilkin, I have some Prussians in my attic'”.

Wilkin, smiling, said the man “showed me photos on his phone and told me someone had given him these bones so he can put them on exhibit… which he refused to do on ethical grounds”.

The remains stayed hidden away until the man met Wilkin, who he believed could analyze them and give them a decent resting place.

A key item of interest in the collection is a right foot with nearly all its toes—that of a “Prussian soldier” according to the middle-aged man.

“To see a foot so well preserved is pretty rare, because usually the small bones on the extremities disappear into the ground,” noted Mathilde Daumas, an anthropologist at the Universite Libre de Bruxelles who is part of the research work.

As for the attributed “Prussian” provenance, the experts are cautious.

A key item of interest in the collection is a right foot with nearly all its toes.

The place it was discovered was the village of Plancenoit, where troops on the Prussian and Napoleonic sides bitterly fought, Wilkin said, holding out the possibility the remains might be those of French soldiers.

Scraps of boots and metal buckles found among the remains do point to uniforms worn by soldiers from the Germanic side arrayed against the French.

But “we know that soldiers stripped the dead for their own gear,” the historian said.

Clothes and accessories are not reliable indicators of the nationality of skeletons found on the Waterloo battlefield, he stressed.

DNA testing

More dependable, these days, are DNA tests.

Dr. Philippe Boxho, a forensic pathologist working on the remains, said there were still parts of the bones that should yield DNA results, and he believed another two months of analyses should yield answers.

The teeth in particular, with traces of strontium, a naturally occurring chemical element that accumulates in human bones, can point to specific regions through their geology.

“As long as the subject matter is dry we can do something. Our biggest enemy is humidity, which makes everything disintegrate,” he explained.

The teeth in particular, with traces of strontium, a naturally occurring chemical element that accumulates in human bones, can point to specific regions through their geology, he said.

Wilkin said an “ideal scenario” for the research would be to find that the remains of the “three to five” soldiers examined came from both the French and Germanic sides.

2023 AFP

Citation:

The two-century-old mystery of Waterloo’s skeletal remains (2023, February 3)