A collaborative study has uncovered evidence of rice beer dating back approximately 10,000 years at the Shangshan site in Zhejiang Province, China, providing new insights into the origins of alcoholic beverage brewing in East Asia.

This discovery highlights the connection between rice fermentation at Shangshan and the region’s cultural and environmental context as well as the broader development of early rice agriculture and social structures.

The study was jointly conducted by researchers from Stanford University, the Institute of Geology and Geophysics (IGG) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Zhejiang Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (ICRA) in China. It was published in the latest issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on Dec. 9.

Uncovering early alcoholic beverage brewing

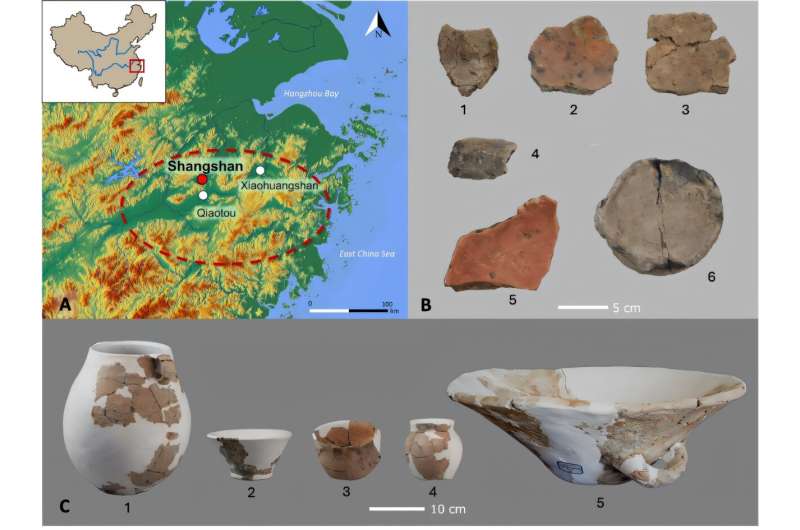

The research team analyzed twelve pottery sherds from the early phase of the Shangshan site in Pujiang County, Zhejiang Province (10,000–9000 BP). “These sherds were associated with various vessel types, including those for fermentation, serving, storage, cooking, and processing,” said Prof. Jiang Leping from ICRA.

The researchers conducted microfossil extraction and analysis on residues from the inner surfaces of the pottery as well as the pottery clay and surrounding cultural layer sediments.

“We focused on identifying phytoliths, starch granules, and fungi, providing insights into the pottery’s uses and the food processing methods employed at the site,” said Prof. Liu Li from Stanford University, the first author of the paper as well as a co-corresponding author.

Phytolith analysis revealed a significant presence of domesticated rice phytoliths in the residues and pottery clay. “This evidence indicates that rice was a staple plant resource for the Shangshan people,” said Prof. Zhang Jianping from IGG, also a co-corresponding author of the study.

Evidence also showed that rice husks and leaves were used in pottery production, further demonstrating the integral role of rice in Shangshan culture.

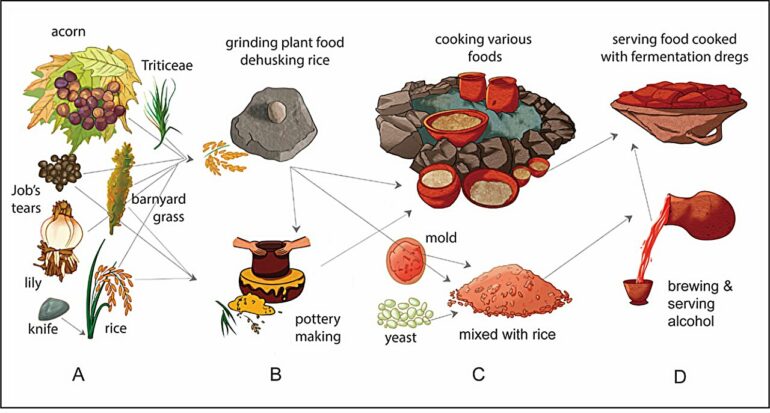

The team also found a variety of starch granules in the pottery residues, including rice, Job’s tears, barnyard grass, Triticeae, acorns, and lilies. Many of the starch granules exhibited signs of enzymatic degradation and gelatinization, which are characteristic of fermentation processes.

Location of the site and artifacts. (A) Location of Shangshan, Qiaotou, and Xiaohuangshan sites, along with the distribution of Shangshan culture. (B) Selected pottery fragments analyzed. (C) Corresponding complete vessels. © IGG

In addition, the study uncovered abundant fungal elements, including Monascus molds and yeast cells, some of which displayed developmental stages typical of fermentation. These fungi are closely associated with qu starters used in traditional brewing methods, such as those used in producing hongqujiu (red yeast rice wine) in China.

The research team analyzed the distribution of Monascus and yeast remains across different pottery vessel types, observing higher concentrations in globular jars compared to a cooking pot and a processing basin. This distribution suggests that vessel types were closely linked to specific functions, with globular jars purposely produced for alcohol fermentation.

The findings suggest that the Shangshan people employed broad-spectrum subsistence strategies during the early phases of rice domestication and used pottery vessels, particularly globular jars, to brew qu-based rice alcoholic beverages.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

Linking technology, agriculture, and climate

The emergence of this brewing technology in the early Shangshan culture was closely linked to rice domestication and the warm, humid climate of the early Holocene.

“Domesticated rice provided a stable resource for fermentation, while favorable climatic conditions supported the development of qu-based fermentation technology, which relied on the growth of filamentous fungi,” said Prof. Liu.

To rule out potential contamination from soil, the researchers analyzed sediment control samples, revealing significantly fewer starch and fungal remains in these samples than in pottery residues.

This finding reinforces the conclusion that the residues were directly associated with fermentation activities. Modern fermentation experiments using rice, Monascus, and yeast further validated the findings by demonstrating morphological consistency with the fungal remains identified on Shangshan pottery.

“These alcoholic beverages likely played a pivotal role in ceremonial feasting, highlighting their ritual importance as a potential driving force behind the intensified utilization and widespread cultivation of rice in Neolithic China,” said Prof. Liu.

The evidence of rice alcohol fermentation at Shangshan represents the earliest known occurrence of this technology in East Asia, offering new insights into the complex interplay between rice domestication, alcoholic beverage production, and social formation during the early Holocene in China.

More information:

Liu, Li et al, Identification of 10,000-year-old rice beer at Shangshan in the Lower Yangzi River valley of China, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2412274121. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2412274121

Provided by

Chinese Academy of Sciences

Citation:

Traces of 10,000-year-old ancient rice beer discovered in Neolithic site in Eastern China (2024, December 9)