A new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change examines the potential cost of unrealized flood risk in the American real estate market, finding that flood zone property prices are overvalued by $121–$237 billion.

Authored by researchers from Environmental Defense Fund, First Street Foundation, Resources for the Future, the Federal Reserve, and several academic institutions, the study also examined how unpriced flood risk throughout the country could impact communities and local governments, finding low-income households particularly vulnerable to home value deflation.

“Increasing flood risk under climate change is creating a bubble that threatens the stability of the US housing market. As we’ve seen in California in the last few weeks, these aren’t hypotheticals and the risk is more extensive than expected—and that risk carries an enormous cost,” said Jesse Gourevitch, a postdoctoral fellow at Environmental Defense Fund and lead author of the study.

“These risks are largely unaccounted for in property transactions, encouraging development in flood-prone areas. Accurately pricing the costs of flooding in home values can support adaptation to flood risk, but may leave many worse off.”

Currently, more than 14.6 million properties in the United States face at least a 1 percent annual probability of flooding, with expected annual damages to residential properties exceeding $32 billion. Increasing frequency and severity of flooding under climate change is predicted to increase the number of properties exposed to flooding by 11 percent and average annual losses by at least 26 percent by 2050.

The increasing cost of flooding under climate change has led to growing concerns that housing markets are mispricing these risks, thus causing a real estate bubble to develop.

“There is a significant amount of ‘unknown’ flood risk across the country based solely on the differences in the publicly available federal flood maps and the reality of actual flood risk. As that unknown risk is realized, there are significant implications for both individual property values and the health of the larger housing market,” said Jeremy Porter, a senior research fellow for First Street Foundation and one of the co-authors of the study.

Low-income households are at greater risk of losing home equity from price deflation due to factoring in anticipated flood risk. The study found that low-income households stand to lose as much as 10 percent of their market value.

“The risk of overvaluation is higher in lower-income communities. For many people, their most valuable asset is their home. We need policy approaches that improve the transparency of climate risk in markets while also providing increased support and protection for frontline communities,” said Carolyn Kousky, Associate Vice President at the Environmental Defense Fund and co-author of the study.

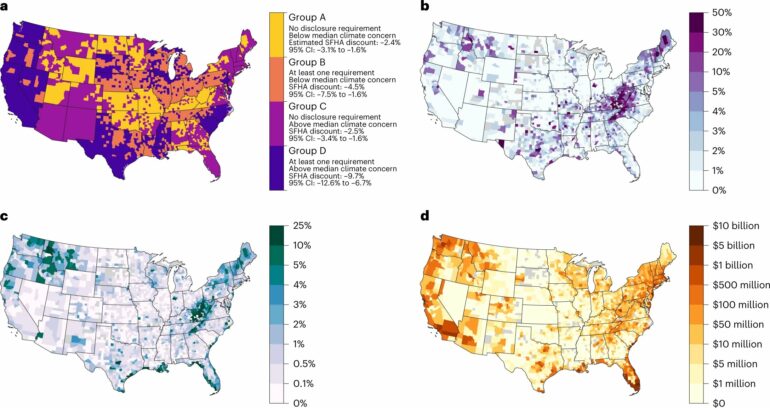

In general, the study found that highly overvalued properties are concentrated in counties along the coast with no flood risk disclosure laws and where there is less concern about climate change. In particular, properties in Florida are overvalued by more than $50 billion.

Aside from the impacts to homeowners, municipalities that are heavily reliant on property taxes for revenue are also highly vulnerable to budgetary shortfalls. These municipalities are concentrated in coastal counties, as well as inland areas in northern New England, eastern Tennessee, central Texas, Wisconsin, Idaho and Montana. In these areas, local governments may need to adapt their fiscal structure in order to continue to provide essential public goods and services.

“This isn’t just a problem for anyone who experiences a flood. This is a problem for cities and towns who could struggle financially if property values—and therefore property taxes—take a dive,” said Penny Liao, a fellow at Resources for the Future and co-author of the study. “We need to think about flood risk not as a homeowner’s problem, but as a problem for our entire community, city and housing market.”

A large portion of overvaluation is driven by properties located outside of the Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA), identified by the United States Federal Emergency Management Agency as having 1-percent chance of being flooded per year. Properties located outside the SFHA comprised 83 percent of all properties at risk of flooding and contribute 69 percent of total overvaluation in dollar terms.

The timing, speed, and extent of devaluation depends on institutional, policy, and regulatory adaptation responses to increasing flood hazards—all of which will impact who bears the financial brunt of climate related disasters: individual homeowners, taxpayers, or mortgage lenders.

“Most of the overvaluation is coming from homes that aren’t currently being told that they have significant risk of flooding. This should be a red flag that local, state and federal governments need to do better to manage and communicate flood risk,” said Gourevitch.

“There is a clear need for improving flood risk communication via updated flood maps, broadening flood risk disclosure laws at the state and federal level and increasing investment in flood risk reduction. And as we decide how to adapt to these risks, decisionmakers will have to grapple with the moral question about who bears the cost.”

The study is the first-ever assessment of climate risk to property values, using the property-specific, climate-adjusted First Street Foundation flood model. To generate these estimates, the authors evaluated the extent to which property values already account for the costs of flooding. They then compared those price discounts with property prices that fully capture expected damages from flooding over the next 30 years.

“The First Street Foundation flood model is the first property level, climate adjusted, risk model that is publicly available for anyone to help close the known information gap regarding flood risk. The precision of that information allows for the uncovering of many new insights, including the contribution of climate-related flood risk to the overvaluation of individual properties and local housing markets,” said Porter.

More information:

Jesse Gourevitch, Unpriced climate risk and the potential consequences of overvaluation in US housing markets, Nature Climate Change (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-023-01594-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41558-023-01594-8

Provided by

Resources for the Future (RFF)

Citation:

US housing market overvalued by $200 billion due to unpriced climate risks, says study (2023, February 16)