X-ray beams aren’t used just by doctors to see inside your body and tell whether you have a broken bone. More powerful beams made up of very short flashes of X-rays can help scientists peer into the structure of individual atoms and molecules and differentiate types of elements.

But getting an X-ray laser beam that delivers super short flashes to capture the fastest processes in nature isn’t easy – it’s a whole science in itself.

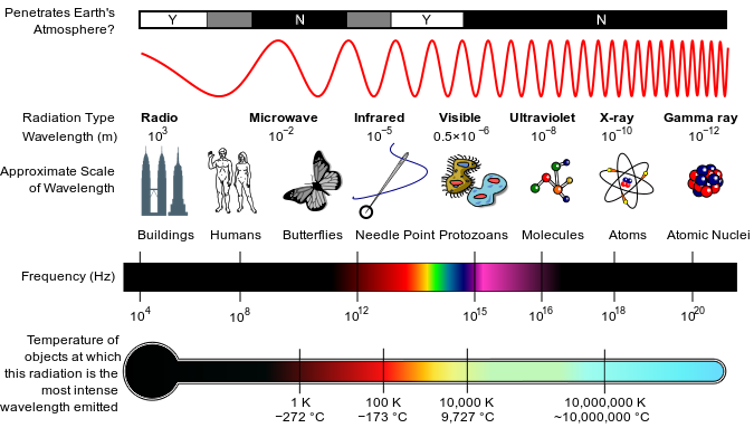

Radio waves, microwaves, the visible light you can see, ultraviolet light and X-rays are all exactly the same phenomenon: electromagnetic waves of energy moving through space. What differentiates them is their wavelength. Waves in the X-ray range have short wavelengths, while radio waves and microwaves are much longer. Different wavelengths of light are useful for different things – X-rays help doctors take snapshots of your body, while microwaves can heat up your lunch.

The rainbow of visible light that you can see is only a small slice of all the kinds of light. While all light is the same phenomenon, it acts differently depending on how long its wavelength is and how high its frequency is.

Inductiveload, NASA/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Optical lasers are devices that emit parallel, or collimated, beams of light. They send out a beam where all the waves have the same wavelength – the red light you get from a laser pointer is one example – and oscillate in synchronicity.

Over the past 15 years, scientists have built X-ray free-electron lasers, which instead of emitting beams of visible light emit X-rays. They are housed in large facilities where electrons travel through a long accelerator – depending on the facility, between a few hundred meters and 1,700 yards – and after passing through a series of thousands of magnets they generate extremely short and powerful X-ray pulses.

The Stanford linear accelerator, shown here from above, is a 1.9-mile-long X-ray free-electron laser.

Peter Kaminski, using data from USGS, CC BY

The pulses are used kind of like flash photography, where the flash – the X-ray pulse – is short enough to capture the fast movement of an object. Researchers have used them as cameras to study how atoms and molecules move and change inside materials or cells.

But while these X-ray free-electron laser pulses are very short and powerful, they’re not the shortest pulses that scientists can make with lasers. By using more advanced technology and taking advantage of the properties some materials have, researchers can create even shorter pulses: in the attosecond region.

One attosecond is one-billionth of a billionth of a second. An attosecond is to one second about what one second is to the 14 billion-year age of the universe. The fastest processes in atoms and molecules happen at the attosecond scale: For instance, it takes electrons attoseconds to move around inside a molecule.