Wet and shivering, I rose from the outrigger of a Polynesian voyaging canoe. We’d been at sea all afternoon and most of the night. I’d hoped to get a little rest, but rain, wind and an absence of flat space made sleep impossible. My companions didn’t even try.

It was May 1972, and I was three months into doctoral research on one of the world’s most remote islands. Anuta is the easternmost populated outpost in the Solomon Islands. It is a half-mile in diameter, 75 miles (120 kilometers) from its nearest inhabited neighbor, and remains one of the few communities where inter-island travel in outrigger canoes is regularly practiced.

A documentary team made a recent visit to Anuta.

My hosts organized a bird-hunting expedition to Patutaka, an uninhabited monolith 30 miles away, and invited me to join the team.

We spent 20 hours en route to our destination, followed by two days there, and sailed back with a 20-knot tail wind. That adventure led to decades of anthropological research on how Pacific Islanders traverse the open sea aboard small craft, without “modern” instruments, and safely arrive at their intended destinations.

Wayfinding techniques vary, depending upon geographic and environmental conditions. Many, however, are widespread. They include mental mapping of the islands in the sailors’ navigational universe and the location of potential destinations in relation to the movement of stars, ocean currents, winds and waves.

Western interest in Pacific voyaging

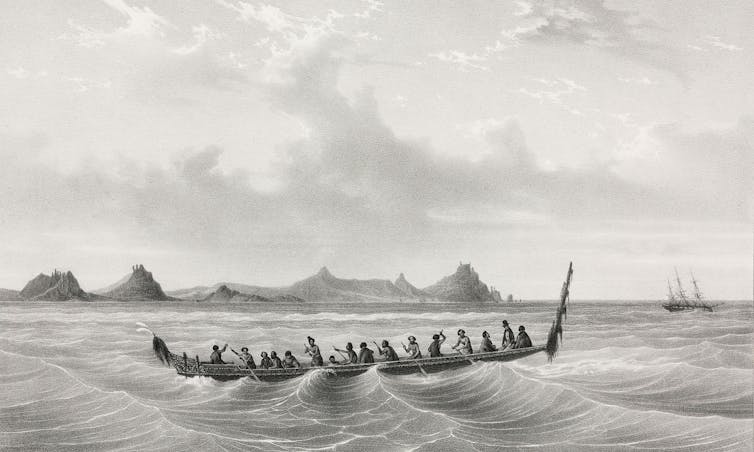

Disney’s two “Moana” movies have shined a recent spotlight on Polynesian voyaging. European admiration for Pacific mariners, however, dates back centuries.

In 1768, the French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville named Sāmoa the “Navigators’ Islands.” The famed British sea captain James Cook reported that Indigenous canoes were as fast and agile as his ships. He welcomed Tupaia, a navigational expert from Ra‘iātea, onto his ship and documented Tupaia’s immense geographic knowledge.

European explorers were impressed by the navigational skills of the people they encountered in the Pacific islands.

Science & Society Picture Library via Getty Images

In 1938, Māori scholar Te Rangi Hīroa (aka Sir Peter Buck) authored “Vikings of the Sunrise,” outlining Pacific exploration as portrayed in Polynesian legend.

In 1947, Thor Heyerdahl, a Norwegian explorer and amateur archaeologist, crossed from Peru to the Tuamotu Islands aboard a balsa wood raft that he named Kon-Tiki, sparking further interest and inspiring a sequence of experimental voyages.

Ten years later Andrew Sharp, a New Zealand-based historian and prominent naysayer, argued that accurate navigation over thousands of miles without instruments is impossible. Others responded with ethnographic studies showing that such voyages were both historic fact and current practice. In…