Do bacteria mutate randomly, or do they mutate for a purpose? Researchers have been puzzling over this conundrum for over a century.

In 1943, microbiologist Salvador Luria and physicist turned biologist Max Delbrück invented an experiment to argue that bacteria mutated aimlessly. Using their test, other scientists showed that bacteria could acquire resistance to antibiotics they hadn’t encountered before.

The Luria–Delbrück experiment has had a significant effect on science. The findings helped Luria and Delbruck win the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1969, and students today learn this experiment in biology classrooms. I have been studying this experiment in my work as a biostatistician for over 20 years.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa.

Decades later, this experiment offers lessons still relevant today, because it implies that bacteria can develop resistance to antibiotics that haven’t been developed yet.

Slot machines and a eureka moment

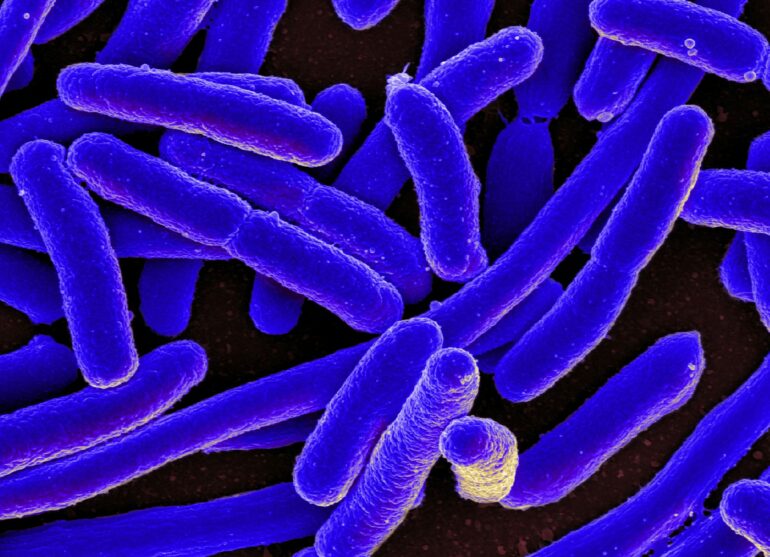

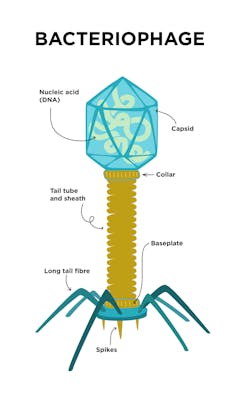

Imagine a test tube containing bacteria living in nutrient broth. The broth is cloudy due to the high concentration of bacteria within it. Adding a virus that infects bacteria, also known as a phage, into the tube kills most of the bacteria and makes the broth clear.

Bacteriophages are viruses that specifically infect bacteria.

Kristina Dukart/iStock via Getty Images Plus

However, keeping the test tube under conditions favorable for bacterial growth will turn the broth cloudy again over time. This indicates that the bacteria developed resistance against the phages and were able to proliferate.

What role did the phages play in this change?

Some scientists thought the phages incited the bacteria to mutate for survival. Others suggested that bacteria routinely mutate randomly, and the development of phage-resistant variants was simply a lucky outcome. Luria and Delbrück had been working together for months to solve this conundrum, but none of their experiments had been successful.

On the night of Jan. 16, 1943, Luria got a hint about how to crack the mystery while watching a colleague hit the jackpot at a slot machine. The next morning, he hurried to his lab.

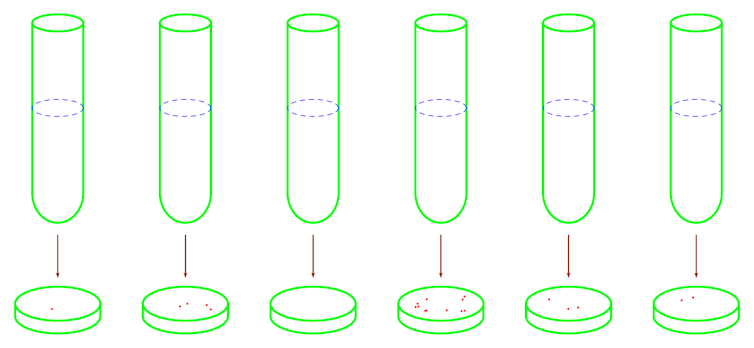

Luria’s experiment consisted of a few tubes and dishes. Each tube contained nutrient broth that would help the bacteria E. coli multiply, while each dish contained material coated with phages. A few bacteria were placed into each tube and given two opportunities to generate phage-resistant variants. They could either mutate in the tubes in the absence of phages, or they could mutate in the dishes in the presence of phages.

This diagram of the Luria-Delbrück experiment depicts colonies of phage-resistant variants of E. coli (red) developing in petri dishes.

Qi Zheng, CC BY-SA

The next day, Luria transferred the bacteria in each tube into a dish filled with phages. The day after that, he counted the…