Imagine a world where your phone stays cool no matter how long you use it, and it’s also equipped with tiny sensors that can identify dangerous chemicals or pollutants with unparalleled sensitivity and precision.

Research published in the journal Nature demonstrates a new way of generating long-wave infrared and terahertz waves, which is an important step toward creating materials that can help realize these technological advances.

The work, led by researchers at the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center (CUNY ASRC), paves the way for cheaper, smaller long-wave infrared light sources and more efficient device cooling.

Phonon-polaritons are a unique type of electromagnetic wave that occurs when light interacts with vibrations in a material’s crystal lattice structure.

These phonon-polariton waves exhibit several unique characteristics. For example, they can concentrate the energy of long-wavelength infrared light into extremely small volumes, even down to tens of nanometers, as well as effectively move heat away from the source.

This makes phonon-polaritons ideal for high-tech applications like sub-wavelength imaging, molecular sensors, and heat management within electronics. However, research on phonon-polariton waves has primarily focused on fundamental studies in laboratory settings, with practical device applications remaining largely unexplored.

“One major challenge is that exciting and detecting phonon-polariton waves is both expensive and inefficient, typically involving costly mid-infrared or terahertz lasers and near-field scanning probes,” said corresponding author Qiushi Guo, a professor with the CUNY ASRC’s Photonics Initiative and the CUNY Graduate Center’s Physics program.

“We wanted to explore whether we could emit phonon-polaritons using just an electrical current, similar to how semiconductor lasers or LEDs work,” Guo said.

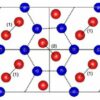

In this study, Guo’s team (in collaboration with researchers from Yale University, California Institute of Technology, Kansas State University and ETH Zurich) found that the key was selecting the right combination of materials: a thin layer of graphene sandwiched between two hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) slabs.

First, in hBN, phonon-polaritons possess a significantly higher density of states and can propagate within the bulk, behaving like deep-subwavelength light rays that bounce back and forth between material boundaries. These specialized phonon-polaritons are referred to as hyperbolic phonon-polaritons (HPhPs).

Graphene is well known for its high electron mobility at room temperature. When encapsulated by hBN slabs, its mobility is further enhanced due to surface passivation and reduced impurities.

“This means that when a current passes through the graphene encapsulated by hBN slabs, electrons in graphene can be accelerated to very high speeds and efficiently scatter with HPhPs in hBN,” Guo explained.

The idea proved successful in the experiment. Remarkably, the team observed the emission of HPhPs when applying a modest electric field of just 1 V/µm to the graphene, highlighting the efficiency of HPhP electroluminescence. The study provides the first experimental demonstration of exciting phonon polariton waves exclusively through electrical methods.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

The study also revealed intriguing physics underlying the HPhP electroluminescence. Specifically, the team identified two possible pathways for HPhP emission.

“When the electron concentration in graphene is low, HPhPs are emitted through interband transitions. However, at higher electron concentrations, HPhP emission occurs through both interband transitions and intraband Cherenkov radiation in graphene,” said former Caltech postdoc Iliya Esin, now an assistant professor of physics at Bar Ilan University, Israel and a corresponding author of the study.

This discovery not only opens new avenues for developing nanoscale long-wave infrared or terahertz light sources but also presents exciting opportunities for energy applications.

During the HPhPs electroluminescence, hot electrons in graphene rapidly lose their excess kinetic energy—the primary cause of overheating. Harnessing this mechanism can enable efficient heat dissipation in electronic devices, according to Guo.

The electrically pumped phonon-polariton light sources open the door to practical, scalable technologies. From next-generation molecular sensing to improved heat management in electronics, this innovation lays the foundation for transformative advancements in energy-efficient, compact technologies that could redefine our modern devices.

More information:

Fengnian Xia, Hyperbolic phonon-polariton electroluminescence in 2D heterostructures, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08686-9. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08686-9

Provided by

CUNY Advanced Science Research Center

Citation:

Good vibrations: Scientists discover a method for exciting phonon-polaritons (2025, March 19)