Metals, as most know them, are good conductors of electricity. That’s because the countless electrons in a metal like gold or silver move more or less freely from one atom to the next, their motion impeded only by occasional collisions with defects in the material.

There are, however, metallic materials at odds with our conventional understanding of what it means to be a metal. In so-called “bad metals”—a technical term, explains Columbia physicist Dmitri Basov—electrons hit unexpected resistance: each other. Instead of the electrons behaving like individual balls bouncing about, they become correlated with one another, clumping up so that their need to move more collectively impedes the flow of an electrical current.

Bad metals may make for poor electrical conductors, but it turns out that they make good quantum materials. In work published on February 13 in the journal Science, Basov’s group unexpectedly observed unusual optical properties in the bad metal molybdenum oxide dichloride (MoOCl2).

Like many materials that researchers at Columbia work with, MoOCl2 is made up of a series of atom-thin layers of different elements. The material is also anisotropic, meaning the properties of each layer will differ depending on which direction the material is being measured from.

“Essentially, the material is a metal if you try to move electrons in one direction, but an insulator if you try to move them in the other,” said Andrew Millis, a physicist at Columbia and the Flatiron Institute who provided theoretical insights into the experimental observations along with Mark van Schilfgaarde and Swagata Acharya from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado.

From that unique directionality, quasiparticles known as hyperbolic plasmon polaritons emerge. Polaritons are a broad category of quasiparticles that form when packets of light called photons interact with a material. Over 70 unique kinds have been described so far, each with unique, hybrid properties. Plasmons, for example, are a type of polariton that occurs when photons pair with electrons as they ripple through a metal—a quantum property known as an electronic oscillation.

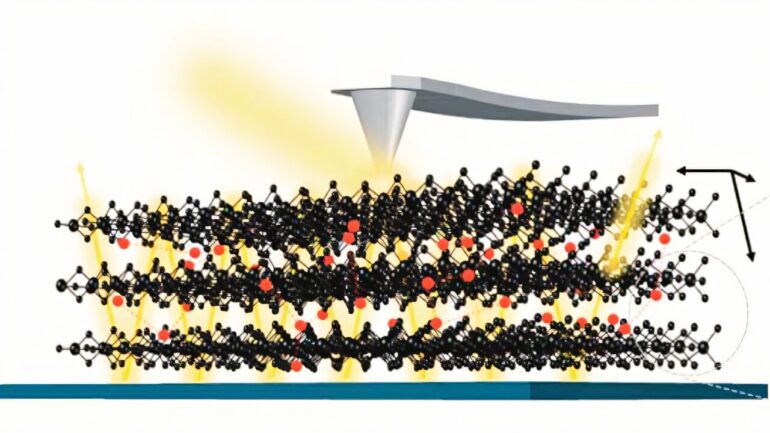

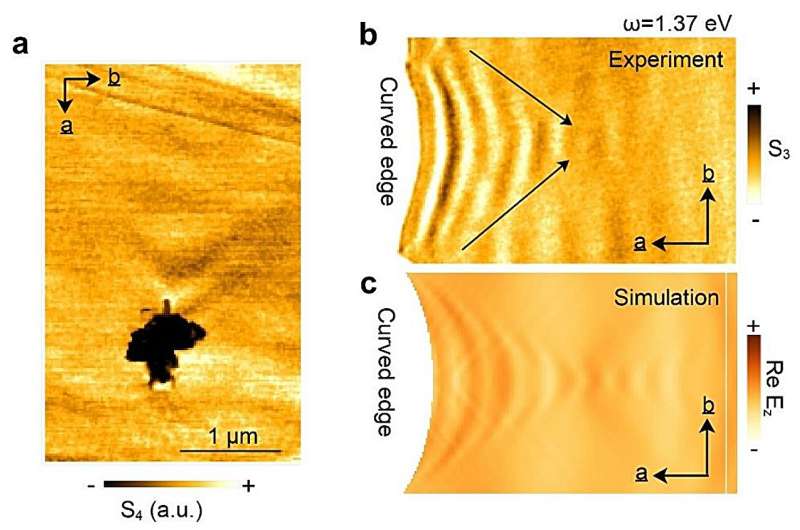

Launching and lensing of in-plane hyperbolic wavefronts. © Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adr5926

Because they pair with the ultra-small quantum world, the various varieties of polaritons allow scientists to focus light into spaces smaller than its wavelength, beyond the so-called diffraction limit. That holds promise for shrinking a number of optical technologies, including creating new kinds of super-resolution microscopes, connecting quantum emitters, and building smaller optical circuits. Hyperbolic plasmons, which move through a material in patterns shaped like arcing hyperbolas rather than the concentric circles characteristic of other polaritons, are particularly well-suited to the task.

A bad metal wasn’t the first place one would think to look for these quasiparticles, given how poorly these metals’ electrons move. Frank Ruta, SEAS’24 and the first author of the current paper, had spent the early days of his Ph.D. hunting for hyperbolic plasmons in samples of metals with better conductivity. Other kinds of plasmons regularly turned up in “good” metals, like gold, but the hyperbolic plasmons that appear in those materials proved fleeting—scientifically interesting, but too short-lived to be of practical use in emerging technologies.

Discover the latest in science, tech, and space with over 100,000 subscribers who rely on Phys.org for daily insights.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates on breakthroughs,

innovations, and research that matter—daily or weekly.

From the literature, though, the group saw hints that MoOCl2 might harbor unique optical properties. Ruta started placing samples under the Basov lab’s scanning near-field optical microscope (s-SNOM), and the bad metal lit up with hyperbolic plasmons.

Notably, the quasiparticles could move across several micrometers of the sample at room temperature and visible and near-infrared light frequencies. Such attributes could make these hyperbolic plasmons especially valuable in technologies like telecommunications and nanofabrication, which operate at these shorter wavelengths.

Optical measurements suggest those good plasmons are related to the energy used: when probed with lower energy, higher wavelength light, the electrons in MoOCl2 bounce around and scatter as expected; as energy increases, that scattering disappears. Experimental collaborators at Berkeley using a technique called angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) offered one possible physical explanation for the scattering: charge density waves. Millis suspects it’s a feature of the peculiar physics that arises from the unique electron-electron interactions in bad metals.

Though full theoretical explanations are still to come, replication is already underway: researchers at the Italian Institute of Technology in Milan independently found evidence of hyperbolic plasmon polaritons in MoOCl2 late last year. The results broaden the experimental options for those hunting for polaritons. “This paper changes our intuitions about which materials to look at,” noted Ruta.

Bad metals might not be so bad after all.

More information:

Francesco L. Ruta et al, Good plasmons in a bad metal, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adr5926

Provided by

Columbia University Quantum Initiative

Citation:

Looking for elusive quantum particles? Try a bad metal, researchers suggest (2025, March 24)