Researchers at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, have shed light on the structure of supercritical water. In this state, which exists at extreme temperatures and pressures, water has the properties of both a liquid and a gas at the same time. According to one theory, the water molecules form clusters, within which they are then connected by hydrogen bonds.

The Bochum-based team has now disproven this hypothesis using a combination of terahertz spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. The results are published in the journal Science Advances.

The experimentalists Dr. Katja Mauelshagen, Dr. Gerhard Schwaab and Professor Martina Havenith from the Chair of Physical Chemistry II collaborated with Dr. Philipp Schienbein and Professor Dominik Marx from the Chair of Theoretical Chemistry.

Supercritical water of interest as a solvent

Supercritical water occurs naturally on Earth, for example in the deep sea, where black smokers—a type of hydrothermal vent—create harsh conditions on the seabed. The threshold for the supercritical state is reached at 374 degrees Celsius and a pressure of 221 bar.

“Understanding the structure of supercritical water could help us to shed light on chemical processes in the vicinity of black smokers,” says Marx, referring to a recent paper published by his research group on this topic. “Due to its unique properties, supercritical water is also of interest as a ‘green’ solvent for chemical reactions; this is because it is environmentally friendly, and at the same time, highly reactive.”

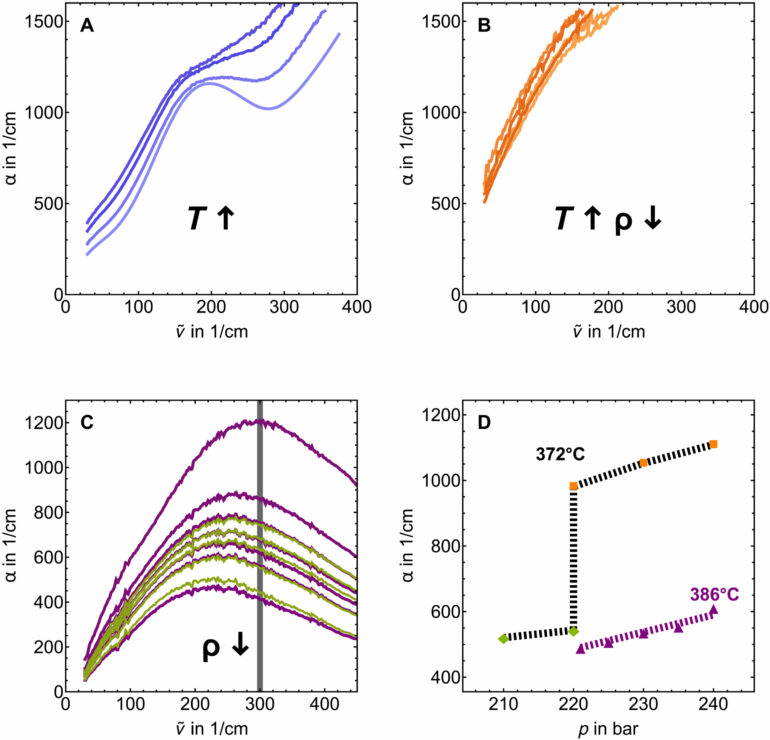

In order to improve the usability of supercritical water, it is necessary to understand the processes inside it in greater detail. Havenith’s team used terahertz spectroscopy for this purpose. While other spectroscopy methods can be employed to investigate H-bonds within a molecule, terahertz spectroscopy sensitively probes the hydrogen bonding between molecules—and thus would allow researchers to detect the formation of clusters in supercritical water, if there are any.

Measuring cells under pressure

“In experimental trials, applying this method to supercritical water was a huge challenge,” explains Havenith. “We need ten-fold larger diameters for our high pressure cells for terahertz spectroscopy than in any other spectral range because we work with longer wavelengths.”

While working on her doctoral thesis, Katja Mauelshagen spent countless hours designing and building a new, suitable cell and optimizing it so that it could withstand the extreme pressure and temperature despite its size.

Eventually, the experimentalists managed to record data from water that was about to enter the supercritical state, as well as from the supercritical state itself. While the terahertz spectra of liquid and gaseous water differed considerably, the spectra of supercritical water and the gaseous state looked virtually identical. This proves that the water molecules form just as few hydrogen bonds in the supercritical state as they do in the gaseous state.

“This means that there are no molecular clusters in supercritical water,” concludes Schwaab.

Schienbein, a member of Marx’s team who calculated the processes in supercritical water using complex ab initio molecular dynamics simulations as part of his doctoral thesis, came to the same conclusion. Just like in the experiment, several hurdles had to be overcome first, such as determining the precise position of the critical point of water in the virtual lab.

The ab initio simulations ultimately showed that two water molecules in the supercritical state remain close to each other only for a short time before separating. Unlike in a hydrogen bond, the bonds between hydrogen and oxygen atoms don’t have a preferred orientation—which is a key property of hydrogen bonds. The direction of the hydrogen-oxygen bond rotates permanently.

“The bonds that exist in this state are extremely short-lived: one hundred times shorter than a hydrogen bond in liquid water,” stresses Schienbein.

The results of the simulations matched the experimental data perfectly, providing a detailed molecular picture of the structural dynamics of water in the supercritical state.

More information:

Katja Mauelshagen et al, Random encounters dominate water-water interactions at supercritical conditions, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adp8614

Provided by

Ruhr-Universitaet-Bochum

Citation:

Supercritical water’s structure decoded: Analysis finds no molecular clusters, just fleeting bonds (2025, March 17)