American beach town boardwalks often boast numerous storefronts advertising saltwater taffies. The candy calls to mind summer vacations, a rainbow assortment of colors and flavors, and a sweetness that sticks to the roof of your mouth.

But when San To Chan received saltwater taffy to celebrate their thesis defense, their first question was not of the flavor but of the physics. When measuring how the taffy responded to applied forces, Chan and their colleagues found taffy occupies the intriguing middle ground between solid and liquid material.

That experience inspired the researchers from Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and Massachusetts Institute of Technology to investigate how the ingredients and confectioning process contribute to the rheology of saltwater taffy. The article, “The rheology of saltwater taffy,” appeared in Physics of Fluids on Sept. 12, 2023.

“Taffy is a viscoelastic material—it has properties between a viscous liquid and an elastic solid,” said author San To Chan. “Comparing the deformation behavior of commercial taffy to those of different lab-made sugar syrups and lab-made taffies allowed us to identify the most important taffy ingredient (and material structure) that governs taffy rheology.”

Despite the name, the candy contains no saltwater. Conventionally, taffies are made with table sugar, water, oil and corn syrup. Additional flavoring and food coloring provide a tasty and eye-catching effect. The mixture is boiled until it reaches a desired state, then cooled.

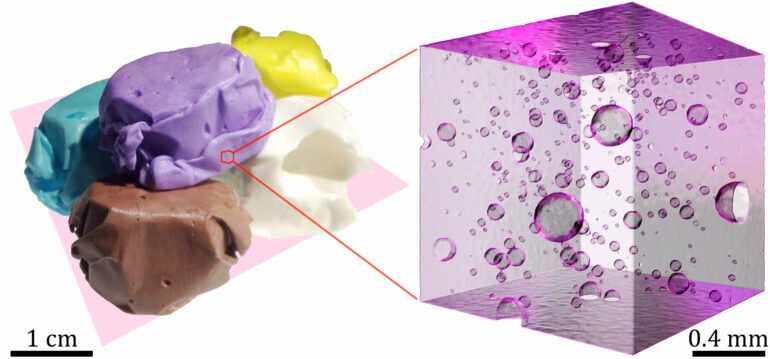

Once cool, the taffy is pulled by hand or machine for several minutes. The stretching and folding aerates and emulsifies the candy, incorporating small air bubbles and breaking down larger oil droplets.

“Taffy is composed of oil droplets and air bubbles of various sizes dispersed in a viscoelastic matrix (sugar syrup),” Chan said. “In some sense, oil droplets and air bubbles are like rubber balls. When deformed in the taffy, they tend to return to their original, spherical shape because of surface tension. In other words, emulsification and aeration make taffy more elastic, hence, chewier.”

The researchers found that air bubbles and oil droplets are the primary factors determining the rheological properties of taffy. Emulsifiers such as lecithin can promote the formation of smaller droplets and prevent them from recombining, leading to a chewier, longer-lasting product.

Armed with more information on how to whip up the desired candy, the researchers hope confectioners can develop new concoctions with novel textures and flavors while helping to maintain the traditional artisan ship involved in confectionery.

There may be another incentive to study the sweet, sticky stuff.

“Because of the larger amount of soy lecithin compared to commercial taffy, the lab-made taffy has a strong soy milk-like flavor, which I like,” said Chan.

More information:

San To Chan et al, The rheology of saltwater taffy, Physics of Fluids (2023). DOI: 10.1063/5.0163715

Provided by

American Institute of Physics

Citation:

The sweet physics of saltwater taffy (2023, September 12)