“Medical illustrators draw what can’t be seen, watch what’s never been done, and tell thousands about it without saying a word.”

For decades, this slogan appeared on the website and printed materials of the Association of Medical Illustrators. Although the association no longer uses this tag line, it’s still an accurate description of the profession.

As a practicing medical illustrator for over 30 years, I draw what can’t be seen and watch what’s never been done on a daily basis. And I teach my students to do the same.

But what exactly does all of that mean, and how does it improve medicine?

Tell thousands about it without saying a word

You may have heard the adage, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” In that same vein, medical illustrators use pictures to teach complex scientific concepts. As the famed medical illustrator Frank H. Netter once said, “(Pictures) eliminate the need for the lecturer or the author to translate what he has in his mind into words and for the listener or the student to translate those words back into a mental image.”

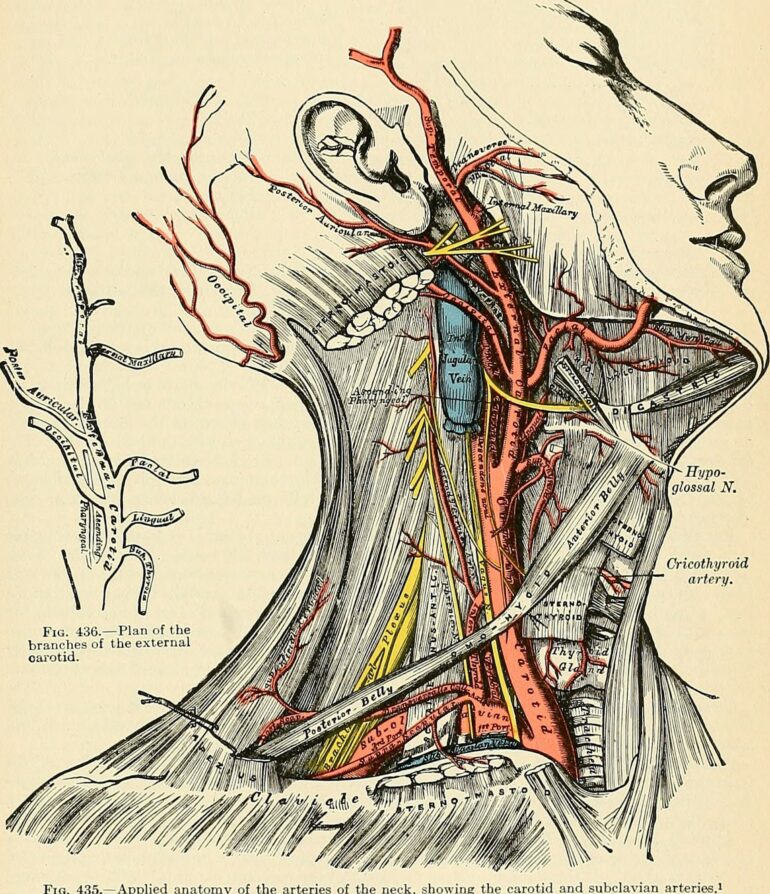

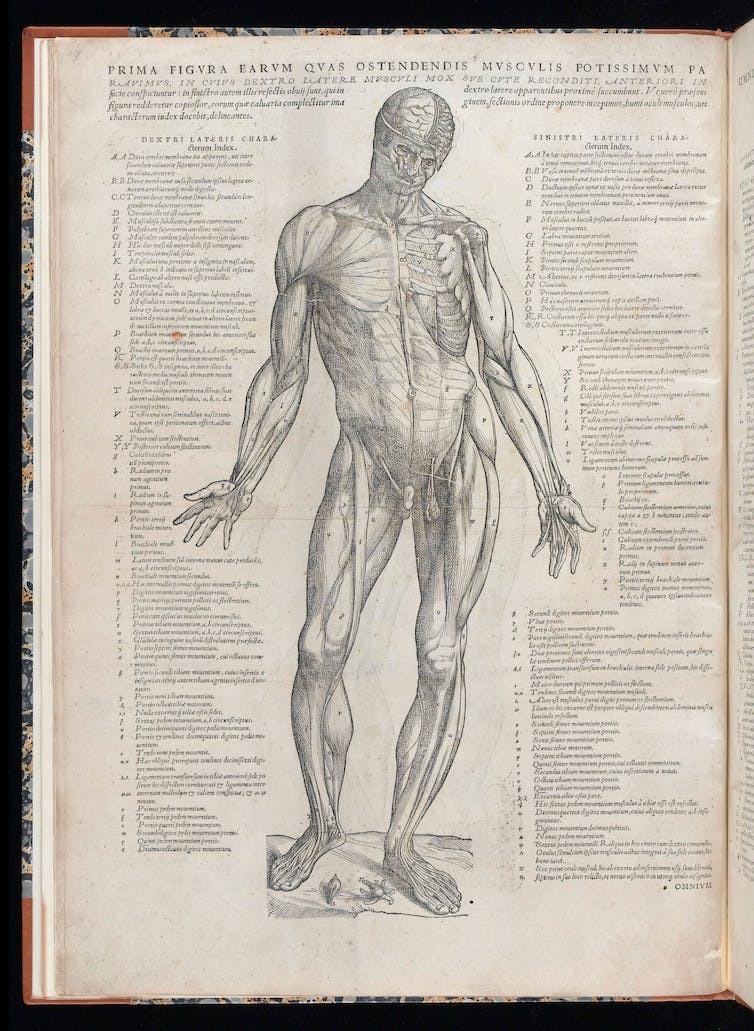

The use of illustrations to communicate medical information has a long history, dating back at least to ancient Egypt and flourishing in the Renaissance. The work of 16th century anatomists Giacomo Berengario da Carpi and Andreas Vesalius set a precedent for the use of detailed illustrations to teach anatomy, a practice that continues to this day.

This is a page from Andreas Vesalius’ ‘Suorum de humani corporis fabrica librorum epitome.’

Andreas Vesalius/Wellcome Collection

The proliferation of illustrated anatomy atlases in the Renaissance coincided with the widespread acceptance of cadaver dissection. The earliest known human dissections were performed in the third century BCE. The practice was prohibited throughout the Middle Ages but became common again in the 13th and 14th centuries.

By the 1500s, dissections, usually of executed criminals, had become public spectacles. The demand for bodies eventually outstripped the supply of executed convicts, leading to the unscrupulous practices of grave robbing and even murder.

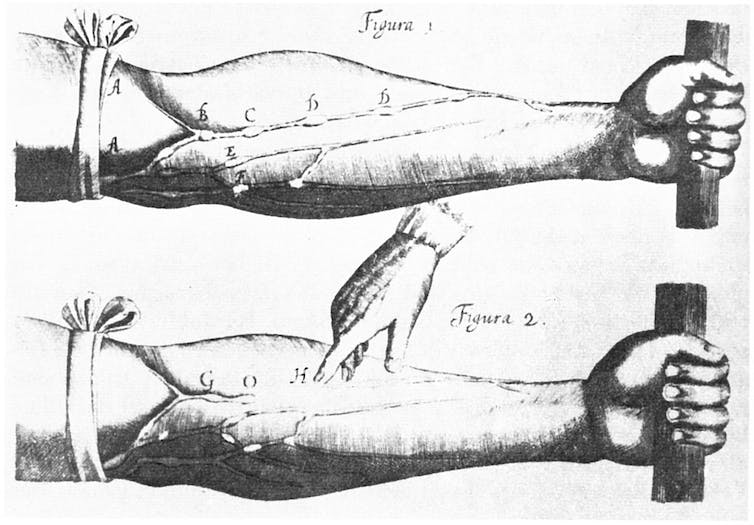

In addition to depicting the location and features of an object such as an organ, illustrations proved essential in describing events happening over time, such as the progression of a disease or the steps in a surgical procedure. Generations of surgeons learned new procedures from meticulously illustrated surgical atlases. An early example of physiology illustration, William Harvey’s classic 17th century work on the circulation of blood, “Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus,” depicts the direction of blood flow through the veins of the forearm.

This image from William Harvey’s ‘Exercitatio’ depicts the direction of normal blood circulation.

William Harvey/Wikimedia Commons

Nowadays, surgeons can practice a procedure…