While developing his theory of natural selection, Charles Darwin was horrified by a group of wasps that lay their eggs within the bodies of caterpillars, with the larvae eating their hosts alive from the inside-out.

Darwin didn’t judge the wasps. Instead, he was troubled by what they revealed about evolution. They showed natural selection to be an amoral process. Any behavior that enhances fitness, nice or nasty, would spread.

Selection isn’t limited to DNA. All systems of inheritance, variation and competition inexorably lead to selection. This includes culture, and I’m one of a team of researchers at Arizona State University’s Institute of Human Origins who use a cultural evolutionary approach to understand human bodies, behavior and society.

Culture shapes everything people do, not least scientific practice – how scientists decide what questions to ask and how to answer them. Good scientific practices lead to public benefits, while poor scientific practices waste time and money.

Scientists vary. They might be meticulous measurement-takers or big-picture visionaries; cautious conservatives or iconoclastic radicals; soft-spoken introverts or ambitious status-seekers. These practices are passed on to the next generation through mentorship: All scientific careers start with years of one-on-one training, where an experienced scientist passes on their approach to their students. A successful scientist can train dozens of graduate students; meanwhile, poor strategies lead to an early career exit.

The currency of scientific success

When scientists apply for jobs or funding, the primary way they compete is through their research papers: reports they write describing their work that are peer-reviewed and published in scholarly journals.

One of the sources of selection on scientists is how these papers are evaluated. Experts can provide detailed assessments, but many hiring or promotion committees use blunter metrics. These include the total number of papers a scientist publishes, how many times their papers are cited – that is, referred to in other work – and their “h-index”: a statistic that blends paper and citation counts into a single number. Journals are rated too, with “impact factors” and “journal ranks.”

All these metrics can incentivize some rather odd outcomes. For instance, citing your own past papers in each new one that you write can inflate your h-index. Some unscrupulous researchers have taken this to the next level, forming “citation cartels” where the members agree to cite one another’s work as much as possible, no matter the quality or relevance.

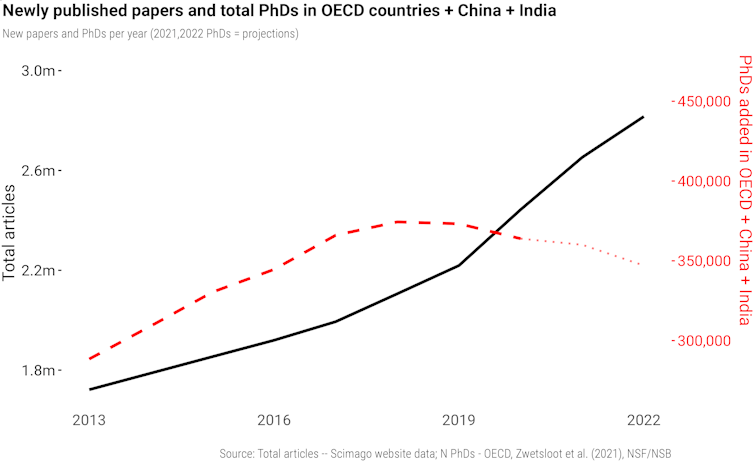

Even as the number of Ph.D. degrees granted has declined, the number of research papers published has drastically increased.

Mark Hanson, Pablo Gómez Barreiro, Paolo Crosetto, Dan Brockington, CC BY

Recently there have been moves away from these simple-yet-flawed metrics. But without better alternatives,…