Does rapid eye movement during sleep reveal where you’re looking at in the scenery of dreams, or are they simply the result of random jerks of our eye muscles? Since the discovery of REM sleep in the early 1950s, the significance of these rapid eye movements has intrigued and fascinated scores of scientists, psychologists and philosophers. REM sleep, as the name implies, is a period of sleep when your eyes move under your closed eyelids. It’s also the period when you experience vivid dreams.

We are researchers who study how the brain processes sensory information during wakefulness and sleep. In our recently published study, we found that the eye movements you make while you sleep may reflect where you’re looking in your dreams.

Dreams occur during the REM stage of sleep.

Measuring dreams

Past studies have attempted to address this question by monitoring the eye movements of people as they slept and waking them up to ask what they were dreaming. The goal was to find a possible connection between the content of a dream just before waking up (say, a car coming in from the left) and the direction the eyes moved at that moment.

Unfortunately, these studies have led to contradictory results. It could be that some participants inaccurately reported dreams, and it’s technically difficult to match a given eye movement to a specific moment in a self-reported dream.

We decided to bypass the problem of dream self-reporting. Instead, we used a more objective way to measure dreams: the electrical activity of a sleeping mouse brain.

Mice, like humans and many other animals, also experience REM sleep. Additionally, they have a sort of internal compass in their brains that gives them a sense of head direction. When the mouse is awake and running around, the electrical activity of this internal compass precisely reports its head direction, or “heading,” as it moves in its environment.

Interestingly, a previous study showed that this internal compass is active during REM sleep. But instead of reporting the actual, fixed head direction of the motionless sleeping mouse, the internal compass kept moving as if the mouse were awake, running around in the virtual environment of its dreams.

Eye movements and head movements are tightly coupled during wakefulness. This means that when people and mice shift their gaze, their heads and eyes turn in the same direction. We reasoned that if eye movements during REM sleep reveal gaze shifts in the world of dreams, those eye movements should occur at the same time and in the same direction as changes in heading in the sleeping mouse’s brain.

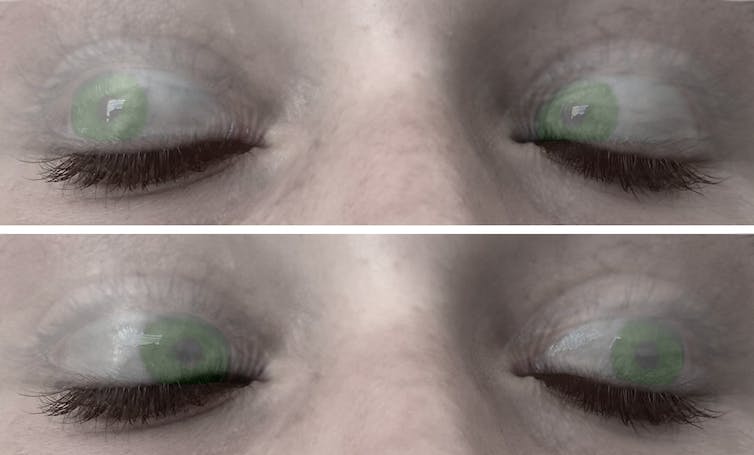

Your eyes may be watching something in your dreams when they move during sleep.

Massimo Scanziani, CC BY-NC-ND

To test this hypothesis, we measured rapid eye movements, or saccades, when mice were awake and mapped this to the electrical activity of…