Every year, northern elephant seals set off on a seven-month, 6,000-mile (10,000-kilometer) journey across the North Pacific ocean in search of fish and squid to eat. They start the journey after sitting on the beach for a couple months – replacing their fur and losing fat – and gradually gain weight over the course of the foraging trip. On these excursions, elephant seals don’t just swim on the surface – they dive continuously, day and night.

To rest, they swim down hundreds of meters below the ocean surface then slowly roll onto their backs and drift back and forth like falling leaves. These dives last around 25 minutes and are called drift dives. The resting period of drift dives is the most dangerous time for an elephant seal: Waking up in the jaws of a white shark or killer whale is not a good way to start the day.

Danielle Dube through an Art-Science Residency with the UC Santa Cruz Norris Center for Natural History, CC BY-ND

We are two biologists studying diving behavior and sleep in marine mammals. Specifically, we are fascinated by the decisions that elephant seals make as they roam the open ocean and navigate extreme changes in their environment and their own bodies. The open ocean is a dangerous place, and animals have to continuously weigh the risks of predation, starvation and exhaustion. Choosing when to rest and when to feed has serious consequences.

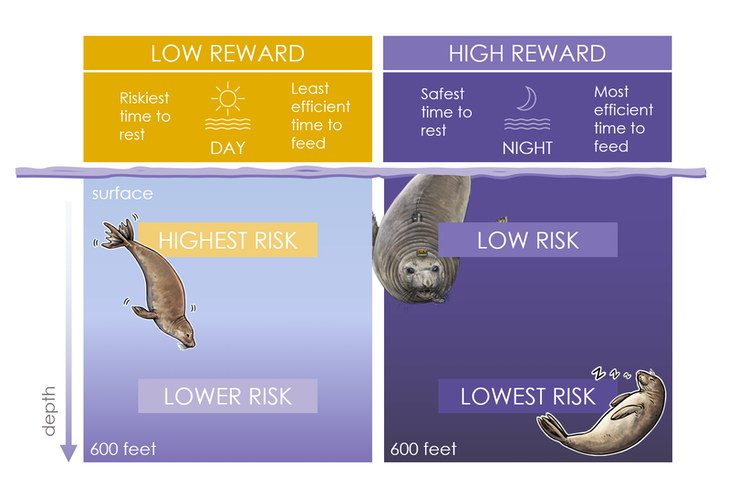

Elephant seals have two options: rest during the safety of the dark night and feed during the day when food is harder to come by, or rest during the day when there is a much higher chance of being eaten by a predator and feed during the night when fish and squid are more available.

So we wondered, do skinny, hungry seals take more risks than plump, healthy seals? Our newest study, just published in the journal Science Advances, reveals that elephant seals fine-tuned their risk–taking behavior throughout the foraging trip.

Risk vs. reward

One simple question is fundamental to ecologists’ understanding of the natural world: Do hungry animals take more risks to find food? This should be true in theory, because wild animals perpetually weigh the risks of starvation and predation. For most species, it is nearly impossible to measure continuous changes in health. As a result, many theories about risk and reward in the animal kingdom have been around for decades but have yet to be tested.

The ocean is a fascinating place to study risk and reward, because light levels determine life and death in three dimensions: The surface of the ocean is bright, and predators can hunt much more easily; but the light quickly fades as you dive deeper into the ocean. For elephant seals, light levels are directly related to risk, because their main predators inhabit shallow waters and use light to hunt. For elephant seals, resting is safer at night when predators can’t find them.

Illustrations by Danielle Dube, Infographic by Jessica Kendall-Bar, CC BY-ND

Light levels are also directly related to reward, because most elephant seal prey – fish and squid – migrates up and down in the water column each day. During the day, when light levels are high, fish and squid remain in the depths to avoid predators. However, at night, when light levels are low, fish and squid swim up closer to the surface to feed on phytoplankton. For seals, foraging is more efficient at night, when prey have emerged from the depths to find their own food.

This means the best time to eat is also the safest time to rest, and seals must pick one behavior over the other. Do they prioritize resting safely or feeding efficiently? And does this change over time as they gain fat?

Dan Costa, CC BY-ND

Drift dives provide the answers

Thanks to a long-term monitoring program led by our colleague Dan Costa, our team had access to dive data from 71 adult female elephant seals tagged with small devices that record time, depth, light, latitude and longitude every four seconds.

Interestingly – and central to this research – when seals perform drift dives, fat seals float upward while skinny seals sink down. This means we can use drifting rates from our dive data to calculate the seals’ percentage of body fat through time. Using data on light, depth and time, we can also approximate risk level. In other words, we know if seals are fat or skinny, and we know how much risk they are taking. Even better, we know both of these metrics continuously over the entire course of their foraging trips.

By simultaneously measuring body fat and risk-taking through time, we learned that elephant seals took more risks when they were skinnier and prioritized safety when they were fatter. Early in the foraging trip, when seals on average had a slim 22% body fat, they rested just after sunrise – 80% of their rest dives occurred during the high-risk daytime. This allowed them to do most of their foraging at night, when food is easier to find.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

Later in the foraging trip, when seals had plumped up to 35% body fat, they rested just before sunrise. Only 30% of their rest dives occurred during the high-risk daytime. Gradual shifts in body condition and behavior over the 220-day foraging trip accumulated to an impressive six–hour shift in average rest time by the end of the trip.

We also discovered that fatter seals rested 300 feet (100 meters) deeper in the water – where it is also 300 times darker – than where thinner seals rested. This further supports the idea that seals are strategically modifying their exposure to light levels – using both rest schedule (time) and rest depth (space) – to minimize risk. We call this the lightscape of fear.

Lessons from seals at sea

Our study provides a window into the real-time decision-making of an elephant seal in the open ocean as it weighs consequences of a nap below the ocean surface. Although light has previously been identified as a critical environmental constraint, no study has continuously monitored an animal’s use of the lightscape relative to extreme shifts in its fat stores and health.

By tracking these metrics together, we were able to better understand the behavior of a wild animal trying to find food while trying to avoid becoming food. Using elephant seals as a model, we can begin to understand how these rules apply to other species – from birds to bats to bears – and scale up to influence entire ecosystems.