Medical researchers have made a surprise anatomical discovery, finding what looks to be a mysterious set of salivary glands hidden inside the human head – which somehow have been missed by scientists for centuries up until now.

This “unknown entity” was identified by accident by doctors in the Netherlands, who were examining prostate cancer patients with an advanced type of scan called PSMA PET/CT. When paired with injections of radioactive glucose, this diagnostic tool highlights tumours in the body.

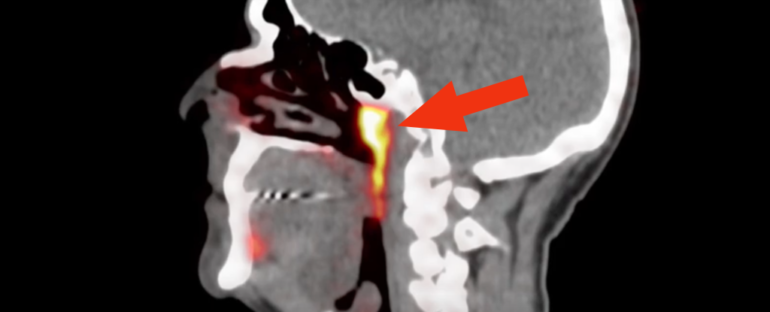

In this case, however, it showed up something else entirely, nestled in the rear of the nasopharynx, and quite the long-time lurker.

(Valstar et al., Radiotherapy and Oncology, 2020)

The tubarial glands structure, indicated by blue arrows, alongside other major salivary glands in orange.

“People have three sets of large salivary glands, but not there,” explains radiation oncologist Wouter Vogel from the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

“As far as we knew, the only salivary or mucous glands in the nasopharynx are microscopically small, and up to 1,000 are evenly spread out throughout the mucosa. So, imagine our surprise when we found these.”

Salivary glands are what produce the saliva essential for our digestive system to function, with the bulk of the fluid produced by the three major salivary glands, known as the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands.

There are approximately 1,000 minor salivary glands too, situated throughout the oral cavity and the aerodigestive tract, but these are generally too small to be seen without a microscope.

The new discovery made by Vogel’s team is much larger, showing what appears to be a previously overlooked pair of glands – ostensibly the fourth set of major salivary glands – located behind the nose and above the palate, close to the centre of the human head.

“The two new areas that lit up turned out to have other characteristics of salivary glands as well,” says first author of the study, oral surgeon Matthijs Valstar from the University of Amsterdam.

“We call them tubarial glands, referring to their anatomical location [above the torus tubarius].”

These tubarial glands were seen to exist in the PSMA PET/CT scans of all the 100 patients examined in the study, and physical investigations of two cadavers – one male and one female – also showed the mysterious bilateral structure, revealing macroscopically visible draining duct openings towards the nasopharyngeal wall.

“To our knowledge, this structure did not fit prior anatomical descriptions,” the researchers explain in their paper.

“It was hypothesised that it could contain a large number of seromucous acini, with a physiological role for nasopharynx/oropharynx lubrication and swallowing.”

As for how the glands haven’t previously been identified, the researchers suggest the structures are found at a poorly accessible anatomical location under the skull base, making them hard to make out endoscopically. It’s possible duct openings could have been noticed, they say, but might not have been noticed for what they are, being part of a larger gland system.

Additionally, it’s only the newer PSMA-PET/CT imaging techniques that would be able to detect the structure as a salivary gland, going beyond the visualisation capabilities of technologies like ultrasound, CT, and MRI scans.

While the team concedes that additional research on a larger, more diverse cohort will be needed to validate their findings, they say the discovery gives us another target to avoid during radiation treatments for patients with cancer, as salivary glands are highly susceptible to damage from the therapy.

Preliminary data – based on a retrospective analysis of 723 patients who underwent radiation treatment – seem to support the conclusion radiation delivered to the tubarial glands region results in greater complications for patients afterwards: a result that not only could benefit future oncology, but also seems to strengthen the case that these mysterious, overlooked structures really are salivary glands.

“It seems like they may be onto something,” pathologist Valerie Fitzhugh from Rutgers University, who wasn’t involved with the study, told The New York Times.

“If it’s real, it could change the way we look at disease in this region.”

The findings are reported in Radiotherapy and Oncology.