Slime is everywhere. It shapes the consistency of your bodily fluids, from the saliva in your mouth to the goo that covers your organs. It protects you against pathogens, including coronavirus, while creating a home in your mouth for billions of friendly bacteria. It helps slugs have Spiderman sex hanging from walls, hagfish turn water into rapidly expanding goo, lampreys filter their food and swiftlets build nests.

But while slime is essential for all forms of complex life, its evolutionary origins have remained murky.

I am an evolutionary geneticist who studies how humans and their genomes evolve. Along with my colleagues, including my long-time collaborator Stefan Ruhl and my student Petar Pajic, we tackled this evolutionary puzzle in our recently published paper. We began by looking into how salivary slime is made in different species. What we found was that slime opens a window into the role that repetitive DNA plays in the mysteries of evolution.

Slime slid into mainstream attention in 2017 when a truck on an Oregon highway overturned and 7,500 pounds (3,402 kilograms) of eel-like hagfish spilled out, slathering nearby vehicles with the slime they produce.

AP Photo/Oregon Police

What are mucins?

Slime is made up of proteins called mucins, which are vessels for sugar molecules. These sugars are the key taskmasters in making things slimy.

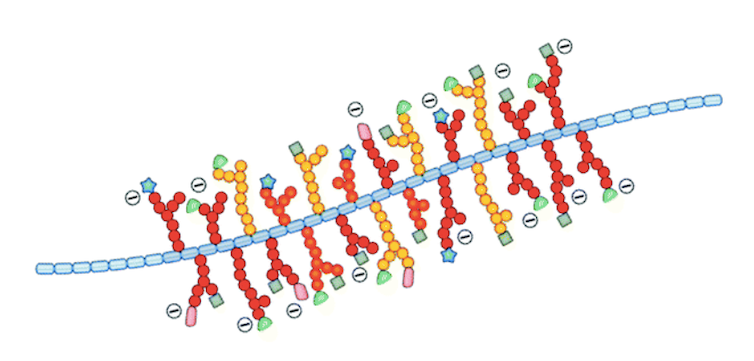

Unlike other proteins, which typically have intricate 3D shapes, mucins often take the shape of long, rigid rods. Sugar molecules are attached along the length of the rods, creating complex, brush-like structures.

Mucins have a long protein backbone with sugars protruding along its length.

Reproduced from Petrou 2018 with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry, CC BY

This partnership between protein building blocks and the sugars bound to them, repeated over and over again, is essential to the properties of mucins. These structures can stick to other mucins and microbes, changing the physical properties of the fluids surrounding them into a sticky and slimy substance.

The evolution of slime

Despite the remarkable properties mucins have and their essential role in biology, how they evolved has eluded scientists.

To begin to figure out the evolutionary origins of mucins, my colleagues and I began by looking for common genetic ancestors for mucins across 49 mammal species. After all, evolution often tinkers but rarely invents. The easiest way for a new gene to evolve is by copying and pasting an existing one and making small changes to the new copy to fit the environmental circumstances. The chances of one species independently inventing a complex mucin from scratch are astronomically small. Our research team was sure that copying and pasting existing mucin genes that then adapt to a particular species’ needs was the main driver of mucin evolution.

But our initial assumptions proved incomplete. Copying…