Ants can be found in nearly every location on Earth, with rough estimates suggesting there are over 10 quadrillion individuals – that is a 1 followed by 16 zeroes, or about 1 million ants per person. Ants are among the most biologically successful animals on the planet.

A surprising part of their evolutionary success is the amazing sense of smell that lets them recognize, communicate and cooperate with one another.

Ants live in complex colonies, sometimes referred to as nests, that are home to a wide range of social interactions. Here, one or more queens are responsible for all the reproduction within that colony. The vast majority of colony members are female workers – sisters that never mate or reproduce and live only to serve the group.

Ants need to defend their colony, seek food and take care of offspring. To accomplish these tasks some ant species domesticate other insects, while others create agricultural systems, harvesting leaves from which they grow edible fungal gardens. Successfully coordinating all these intricate tasks requires reliable and secure communication among nestmates.

We are biologists who study the remarkable sensory abilities of ants. Our recent work shows how their societies depend on the exchange of reliable information which, if disrupted, spells doom for their colonies.

Unique scents

Human communication relies primarily on verbal and visual cues. We usually identify our friends by the sound of their voice, the appearance of their face or the clothes they wear. Ants, however, rely primarily on their acute sense of smell.

An exterior shell, known as an exoskeleton, encases an ant’s body. This greasy coat carries a unique scent that varies from individual to individual and gives each ant a unique odor signature that other ants can detect. This odor signature can communicate important information.

The queen, for example, will smell slightly different from a worker, and thus receive special treatment within the colony. Importantly, ants from different colonies will smell slightly different from one another. The detection and decoding of these differences is vital for colony defense and can trigger aggressive turf wars between colonies when ants catch a whiff of intruders.

Interactions between nestmates are friendly. But when ants sniff out enemy non-nestmates, there is rapid and deadly aggression. Produced by the Zwiebel Lab, Vanderbilt University, filmed by Stephen Ferguson.

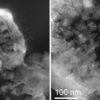

For ants and other insects, receiving chemical information begins when an odor enters the small hairs located along their antennae. These hairs are hollow and contain special receptors, called chemosensory neurons, that sort and send the chemical information to the ant’s brain.

Odors, such as those given off from an ant’s greasy coat, act like chemical “keys.” Ants can smell these odor keys only if they are inserted into the correct set of…