In my research focused on early farmers of Europe, I have often wondered about a curious pattern through time: Farmers lived in large dense villages, then dispersed for centuries, then later formed cities again, only to abandon those as well. Why?

Archaeologists often explain what we call urban collapse in terms of climate change, overpopulation, social pressures or some combination of these. Each likely has been true at different points in time.

But scientists have added a new hypothesis to the mix: disease. Living closely with animals led to zoonotic diseases that came to also infect humans. Outbreaks could have led dense settlements to be abandoned, at least until later generations found a way to organize their settlement layout to be more resilient to disease. In a new study, my colleagues and I analyzed the intriguing layouts of later settlements to see how they might have interacted with disease transmission.

Modern excavations at what was once Çatalhöyük, where inhabitants lived in mud-brick houses that weren’t separated by paths or streets.

Murat Özsoy 1958/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Earliest cities: Dense with people and animals

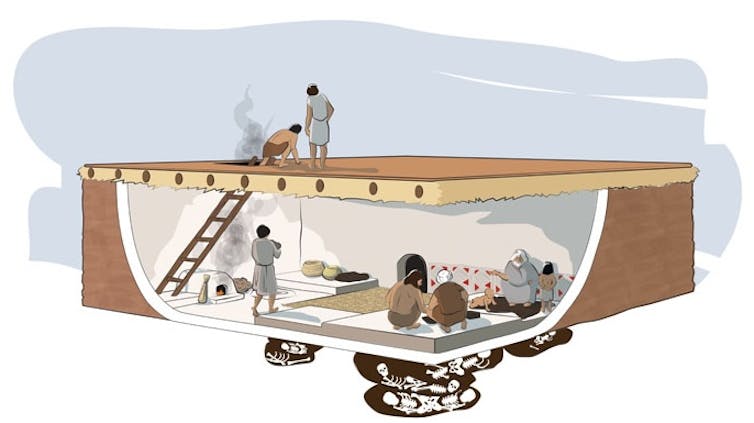

Çatalhöyük, in present-day Turkey, is the world’s oldest farming village, from over 9,000 years ago. Many thousands of people lived in mud-brick houses jammed so tightly together that residents entered via a ladder through a trapdoor on the roof. They even buried selected ancestors underneath the house floor. Despite plenty of space out there on the Anatolian Plateau, people packed in closely.

Homes at Çatalhöyük were so tightly packed that people entered through the roof and even buried some ancestors beneath the floor.

Illustration by Kathryn Killackey and The Çatalhöyük Research Project

For centuries, people at Çatalhöyük herded sheep and cattle, cultivated barley and made cheese. Evocative paintings of bulls, dancing figures and a volcanic eruption suggest their folk traditions. They kept their well-organized houses tidy, sweeping floors and maintaining storage bins near the kitchen, located under the trapdoor to allow oven smoke to escape. Keeping clean meant they even replastered their interior house walls several times a year.

These rich traditions ended by 6000 BCE, when Çatalhöyük was mysteriously abandoned. The population dispersed into smaller settlements out in the surrounding flood plain and beyond. Other large farming populations of the region had also dispersed, and nomadic livestock herding became more widespread. For those populations that persisted, the mud-brick houses were now separate, in contrast with the agglomerated houses of Çatalhöyük.

Was disease a factor in the abandonment of dense settlements by 6000 BCE?

At Çatalhöyük, archaeologists have found human bones intermingled with cattle bones in burials and refuse heaps. Crowding of people and animals likely bred