The surface of Uranus’ moon Ariel is coated with a significant amount of carbon dioxide ice, especially on its “trailing hemisphere” that always faces away from the moon’s direction of orbital motion. This fact presents a surprise because even at the frigid reaches of the Uranian system—20 times farther from the sun than Earth—carbon dioxide readily turns to gas and is lost to space.

Scientists have theorized that something is supplying carbon dioxide to Ariel’s surface. Some favor the idea that interactions between the moon’s surface and charged particles in Uranus’ magnetosphere create carbon dioxide through a process called radiolysis, in which molecules are broken down by ionizing radiation.

But a new study published July 24 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters tips the scales in favor of an alternative theory—that carbon dioxide and other molecules are emerging from inside Ariel, possibly even from a subsurface liquid ocean.

Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to collect chemical spectra of the moon and then comparing them with spectra of simulated chemical mixtures in the lab, a research team led by Richard Cartwright from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, found that Ariel has some of the most carbon dioxide-rich deposits in the solar system, adding up to an estimated 10 millimeters (0.4 inches) or more thickness on the moon’s trailing hemisphere.

Among those deposits was another puzzling finding: the first clear signals of carbon monoxide.

“It just shouldn’t be there. You’ve got to get down to 30 Kelvin [minus 405 degrees Fahrenheit] before carbon monoxide’s stable,” Cartwright said. Ariel’s surface temperature, meanwhile, averages around 65 F warmer. “The carbon monoxide would have to be actively replenished, no question.”

Radiolysis could still be responsible for some of that replenishment, he added. Lab experiments have shown that radiation bombardment of water ice mixed with carbon-rich material can produce both carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. Thus, radiolysis can provide a restocking source and account for the rich abundance of both molecules on Ariel’s trailing hemisphere.

But many questions remain about the Uranian magnetosphere and the extent of its interactions with the planet’s moons. Even during Voyager 2’s flyby of Uranus nearly 40 years ago, scientists suspected such interactions might be limited because Uranus’ magnetic field axis and the orbital plane of its moons are offset from each other by about 58 degrees. Recent models have supported that prediction.

Instead, the bulk of the carbon oxides may come from chemical processes that happened (or are still happening) in a water ocean beneath Ariel’s icy surface, escaping either through cracks in the moon’s icy exterior or possibly even through eruptive plumes.

What’s more, the new spectral observations hint that Ariel’s surface may also harbor carbonate minerals—salts that can be made only through the interaction of liquid water with rocks.

“If our interpretation of that carbonate feature is correct, then that is a pretty big result because it means it had to form in the interior,” Cartwright said. “That’s something we absolutely need to confirm, either through future observations, modeling or some combination of techniques.”

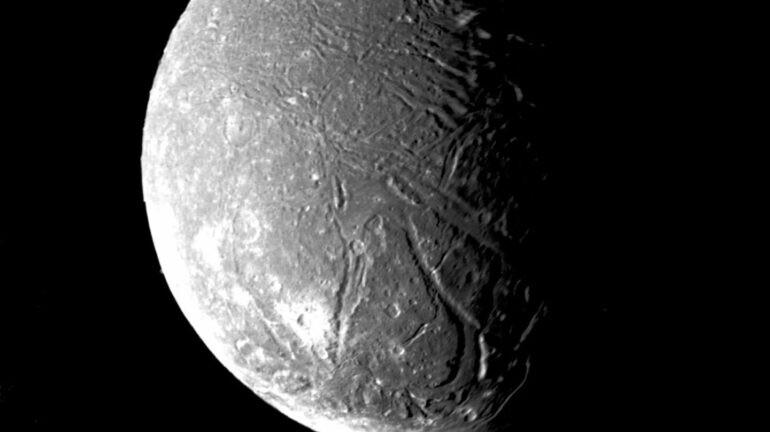

With Ariel’s surface covered in gash-like canyons, crisscrossing grooves and smooth spots that are thought to be from cryovolcanic spills, researchers have already suspected the moon was or still may be active.

A 2023 study led by APL’s Ian Cohen even suggested that Ariel and/or its sister moon Miranda could be emitting material into Uranus’ magnetosphere, including possibly through plumes.

“All these new insights underscore how compelling the Uranian system is,” Cohen said. “Whether it’s to unlock the keys to how the solar system formed, better understand the planet’s complex magnetosphere or determine whether these moons are potential ocean worlds, many of us in the planetary science community are really looking forward to a future mission to explore Uranus.”

In 2023, through its Planetary Science and Astrobiology decadal survey, the planetary science community prioritized the first dedicated mission to Uranus, raising hopes that a scientific voyage to the turquoise ice giant is on the horizon.

Cartwright sees that as an opportunity to collect valuable data about the solar system’s ice giants and their potentially ocean-bearing moons, both of which have applications to the worlds being discovered in other stellar systems.

But it’s also a chance to finally receive concrete answers that are only possible by being in the system. For example, most of Ariel’s observed grooves—suspected openings to its interior—are on its trailing side. If carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide are somehow leaking through those grooves, it could provide an alternate explanation for why they’re so much more abundant on Ariel’s trailing side.

“It’s a bit of a stretch because we just haven’t seen much of the moon’s surface,” Cartwright cautioned. Voyager 2 captured only around 35% of Ariel’s surface during its brief flyby. “We’re just not going to know until we perform more dedicated observations,” he said.

More information:

Richard J. Cartwright et al, JWST Reveals CO Ice, Concentrated CO2 Deposits, and Evidence for Carbonates Potentially Sourced from Ariel’s Interior, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2024). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ad566a

Provided by

Johns Hopkins University

Citation:

Carbon oxides on Uranus’ moon Ariel hint at hidden ocean, Webb telescope reveals (2024, July 25)