Located 163 light-years from Earth, a Jupiter-sized exoplanet named WASP-69b offers astrophysicists a window into the dynamic processes that shape planets across the galaxy. The star it orbits is baking and stripping away the planet’s atmosphere, and that escaped atmosphere is being sculpted by the star into a vast, cometlike tail at least 350,000 miles long.

I’m an astrophysicist. My research team published a paper in the Astrophysical Journal describing how and why WASP-69b’s tail formed, and what its formation can illuminate about the other types of planets astronomers tend to detect outside of our solar system.

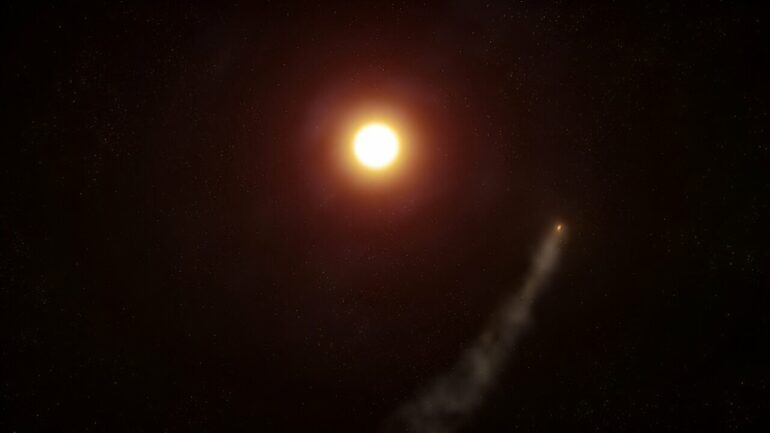

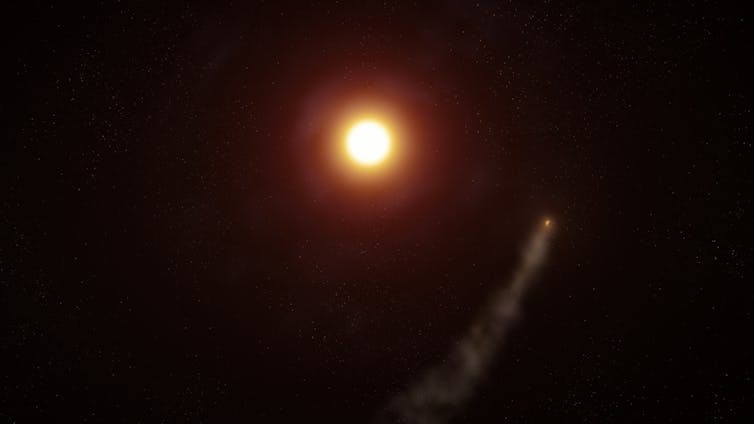

Artist’s interpretation of an aerial view of the exoplanet WASP-69b on its 3.8-day orbit around its host star. Its atmosphere is being stripped away and sculpted into a long cometlike tail that trails the planet.

W. M. Keck Observatory/Adam Makarenko

A universe filled with exoplanets

When you look up at the night sky, the stars you see are suns, with distant worlds, known as exoplanets, orbiting them. Over the past 30 years, astronomers have detected over 5,600 exoplanets in our Milky Way galaxy.

It isn’t easy to detect a planet light-years away. Planets pale in comparison, in both size and brightness, to the stars that they orbit. But despite these limitations, exoplanet researchers have uncovered an astonishing variety – everything from small rocky worlds barely larger than our own moon to gas giants so colossal that they’ve been dubbed “super-Jupiters.”

However, the most common exoplanets astronomers detect are larger than Earth, smaller than Neptune, and orbit their stars more closely than Mercury orbits our Sun.

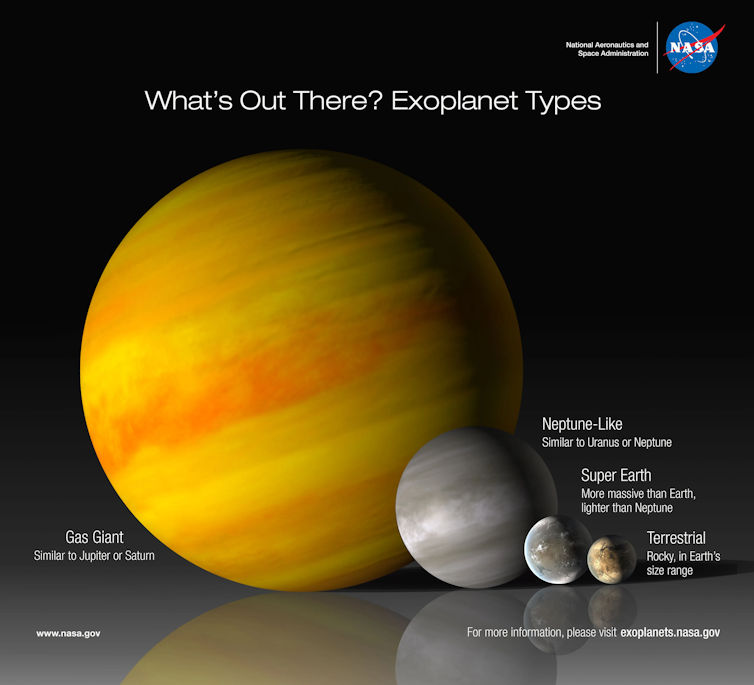

These ultra-common planets tend to fall into one of two distinct groups: super-Earths and sub-Neptunes. Super-Earths have a radius that’s up to 50% larger than Earth’s radius, while sub-Neptunes typically have a radius that’s two to four times larger than Earth’s radius.

Sub-Neptunes, or Neptune-like planets, look at lot like a super-Earth, but with a thick atmosphere.

NASA-JPL/Caltech

Between those two radius ranges, there’s a gap, known as the “Radius Gap,” in which researchers rarely find planets. And, Neptune-sized planets that complete orbits around their stars in less than four days are exceedingly rare. Researchers call that gap the “Hot Neptune Desert.”

Some underlying astrophysical processes must be preventing these planets from forming – or surviving.

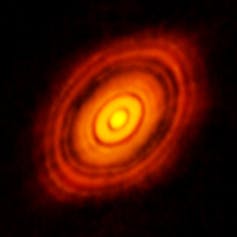

Planet formation

As a star forms, a large disk of dust and gas forms around it. In that disk, planets can form. As young planets gain mass, they can accumulate significant gas atmospheres. But as the star matures, it starts to emit high amounts of energy in the form of ultraviolet and X-ray radiation. This stellar radiation can bake away the atmospheres that the planets have accumulated in a process called photoevaporation.

…