With the first paper compiling all known information about planets like Venus beyond our solar system, scientists are the closest they’ve ever been to finding an analog of Earth’s “twin.”

If they succeed in locating one, it could reveal valuable insights into Earth’s future, and our risk of developing a runaway greenhouse climate as Venus did.

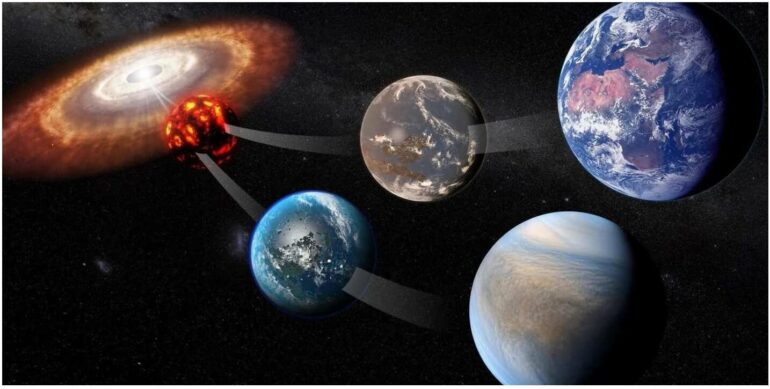

Scientists who wrote the paper began with more than 300 known terrestrial planets orbiting other stars, called exoplanets. They whittled the list down to the five most likely to resemble Venus in terms of their radii, masses, densities, the shapes of their orbits, and perhaps most significantly, distances from their stars.

The paper, published in The Astronomical Journal, also ranked the most Venus-like planets in terms of the brightness of the stars they orbit, which increases the likelihood that the James Webb Space Telescope would get more informative signals regarding the composition of their atmospheres.

Today’s Venus floats in a nest of sulfuric acid clouds, has no water, and features surface temperatures of up to 900 degrees Fahrenheit—hot enough to melt lead. Using the Webb telescope to observe these possible Venus analogs, or “exoVenuses,” scientists hope to learn if things were ever different for our Venus.

“One thing we wonder is if Venus could once have been habitable,” said Colby Ostberg, lead study author and UC Riverside Ph.D. student. ‘To confirm this, we want to look at the coolest of the planets in the outer edge of the Venus zone, where they get less energy from their stars.”

The Venus Zone is a concept proposed by UCR astrophysicist Stephen Kane in 2014. It is similar to the concept of a habitable zone, which is a region around a star where liquid surface water could exist.

“The Venus Zone is where it would be too hot to have water, but not hot enough that the planet’s atmosphere gets stripped away,” Ostberg explained. “We want to find planets that still have significant atmospheres.”

Finding a planet similar to Venus in terms of planet mass is also important because mass affects how long a planet is able to maintain an active interior, with the movement of rocky plates across its outer shell known as plate tectonics.

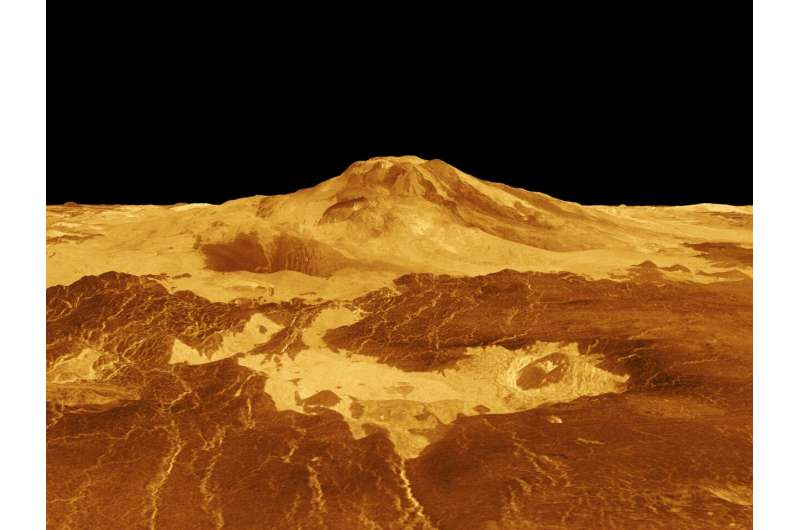

Maat Mons is a massive shield volcano on the planet Venus and the planet’s second-highest mountain and highest volcano. © NASA/JPL

“Venus has 20% less mass than Earth, and as a result, scientists believe there may not be any tectonic activity there. Therefore, Venus has a hard time taking carbon out of its atmosphere,” Ostberg explained. “The planet just can’t get rid of it.”

Another aspect of an active planet interior is volcanic activity, and evidence uncovered just this month suggests Venus still has active volcanoes. “The large number of Venus analogs identified in our paper will allow us to test if such volcanic activity is the norm amongst similar planets, or not,” said Kane, who co-authored the study.

The research team is proposing the planets identified in the paper as targets for the Webb telescope in 2024. Webb is the most expensive and advanced observation tool ever created and will enable scientists not only to see whether the exoVenuses have atmospheres, but also what they’re made of.

The Webb observations may reveal biosignature gases in the atmosphere of an exoVenus, such as methane, methyl bromide or nitrous oxide, which could signal the presence of life.

“Detecting those molecules on an exoVenus would show that habitable worlds can exist in the Venus Zone and strengthen the possibility of a temperate period in Venus’ past,” Ostberg said.

These observations will be complemented by NASA’s two upcoming missions to Venus, in which Kane will play an active role. The DAVINCI mission will also measure gases in the Venusian atmosphere, while the VERITAS mission will enable 3-D reconstructions of the landscape.

All of these observations are leading toward the ultimate question that Kane poses in much of his work, which attempts to understand the Earth-Venus divergence in climate: “Is Earth weird or is Venus the weird one?”

“It could be that one or the other evolved in an unusual way, but it’s hard to answer that when we only have two planets to analyze in our solar system, Venus and Earth. The exoplanet explorations will give us the statistical power to explain the differences we see,” Kane said.

If the planets on the new list turn out to indeed be much like Venus, that would show the outcome of Venus’ evolution is common.

“That would be a warning for us here on Earth because the danger is real. We need to understand what happened there to make sure it doesn’t happen here,” Kane said.

More information:

Colby Ostberg et al, The Demographics of Terrestrial Planets in the Venus Zone, The Astronomical Journal (2023). DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/acbfaf

Provided by

University of California – Riverside

Citation:

Hunting Venus 2.0: Study narrows James Webb Space Telescope targets (2023, March 22)