University of Arizona astronomers have identified five examples of a new class of stellar system. They’re not quite galaxies and only exist in isolation.

The new stellar systems contain only young, blue stars, which are distributed in an irregular pattern and seem to exist in surprising isolation from any potential parent galaxy.

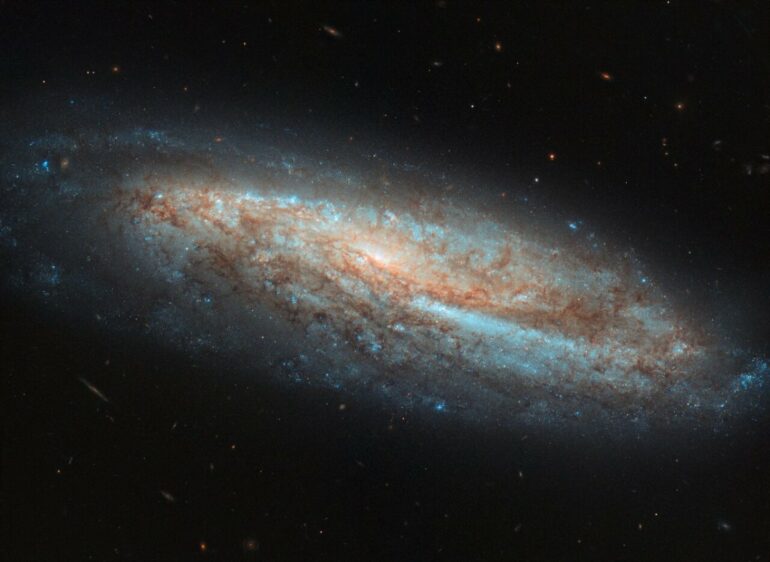

The stellar systems—which astronomers say appear through a telescope as “blue blobs” and are about the size of tiny dwarf galaxies—are located within the relatively nearby Virgo galaxy cluster. The five systems are separated from any potential parent galaxies by more than 300,000 light years in some cases, making it challenging to identify their origins.

The astronomers found the new systems after another research group, led by the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy’s Elizabeth Adams, compiled a catalog of nearby gas clouds, providing a list of potential sites of new galaxies. Once that catalog was published, several research groups, including one led by UArizona associate astronomy professor David Sand, started looking for stars that could be associated with those gas clouds.

The gas clouds were thought to be associated with our own galaxy, and most of them probably are, but when the first collection of stars, called SECCO1, was discovered, astronomers realized that it was not near the Milky Way at all, but rather in the Virgo cluster, which is much farther away but still very nearby in the scale of the universe.

SECCO1 was one of the very unusual “blue blobs,” said Michael Jones, a postdoctoral fellow in the UArizona Steward Observatory and lead author of a study that describes the new stellar systems. Jones presented the findings, which Sand co-authored, during the 240th American Astronomical Society meeting in Pasadena, California, Wednesday.

“It’s a lesson in the unexpected,” Jones said. “When you’re looking for things, you’re not necessarily going to find the thing you’re looking for, but you might find something else very interesting.”

The team obtained their observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, the Very Large Array telescope in New Mexico and the Very Large Telescope in Chile. Study co-author Michele Bellazzini, with the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica in Italy, led the analysis of the data from Very Large Telescope and has submitted a companion paper focusing on that data.

Together, the team learned that most of the stars in each system are very blue and very young and that they contain very little atomic hydrogen gas. This is significant because star formation begins with atomic hydrogen gas, which eventually evolves into dense clouds of molecular hydrogen gas before forming into stars.

“We observed that most of the systems lack atomic gas, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t molecular gas,” Jones said. “In fact, there must be some molecular gas because they are still forming stars. The existence of mostly young stars and little gas signals that these systems must have lost their gas recently.”

The combination of blue stars and lack of gas was unexpected, as was a lack of older stars in the systems. Most galaxies have older stars, which astronomers refer to as being “red and dead.”

“Stars that are born red are lower mass and therefore live longer than blue stars, which burn fast and die young, so old red stars are usually the last ones left living,” Jones said. “And they’re dead because they don’t have any more gas with which to form new stars. These blue stars are like an oasis in the desert, basically.”

The fact that the new stellar systems are abundant in metals hints at how they might have formed.

“To astronomers, metals are any element heavier than helium,” Jones said. “This tells us that these stellar systems formed from gas that was stripped from a big galaxy, because how metals are built up is by many repeated episodes of star formation, and you only really get that in a big galaxy.”

There are two main ways gas can be stripped from a galaxy. The first is tidal stripping, which occurs when two big galaxies pass by each other and gravitationally tear away gas and stars.

The other is what’s known as ram pressure stripping.

“This is like if you belly flop into a swimming pool,” Jones said. “When a galaxy belly flops into a cluster that is full of hot gas, then its gas gets forced out behind it. That’s the mechanism that we think we’re seeing here to create these objects.”

The team prefers the ram pressure stripping explanation because in order for the blue blobs to have become as isolated as they are, they must have been moving very quickly, and the speed of tidal stripping is low compared to ram pressure stripping.

Astronomers expect that one day these systems will eventually split off into individual clusters of stars and spread out across the larger galaxy cluster.

What researchers have learned feeds into the larger “story of recycling of gas and stars in the universe,” Sand said. “We think that this belly flopping process changes a lot of spiral galaxies into elliptical galaxies on some level, so learning more about the general process teaches us more about galaxy formation.”

More information:

Michael G. Jones et al, Young, blue, and isolated stellar systems in the Virgo Cluster. II. A new class of stellar system. arXiv:2205.01695v1 [astro-ph.GA], arxiv.org/abs/2205.01695

Provided by

University of Arizona

Citation:

Mysterious blue blobs could be galactic ‘belly flops,’ astronomers say (2022, June 16)