In images from NASA’s retired Spitzer Space Telescope, streams of dust thousands of light-years long flow toward the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Andromeda galaxy. It turns out these streams can help explain how black holes billions of times the mass of our sun satiate their big appetites but remain “quiet” eaters.

As supermassive black holes gobble up gas and dust, the material gets heated up just before it falls in, creating incredible light shows—sometimes brighter than an entire galaxy full of stars. When the material is consumed in clumps of different sizes, the brightness of the black hole fluctuates.

But the black holes at the center of the Milky Way (Earth’s home galaxy) and Andromeda (one of our nearest galactic neighbors) are among the quietest eaters in the universe. What little light they emit does not vary significantly in brightness, suggesting they are consuming a small but steady flow of food rather than large clumps. The streams approach the black hole little by little and in a spiral, similar to the way the water swirls down a drain.

Hunting for Andromeda’s food source

A study published in The Astrophysical Journal took the hypothesis that a quiet supermassive black hole feeds on a steady stream of gas and applied it to the Andromeda galaxy. Using computer models, the authors simulated how gas and dust in proximity to Andromeda’s supermassive black hole might behave over time.

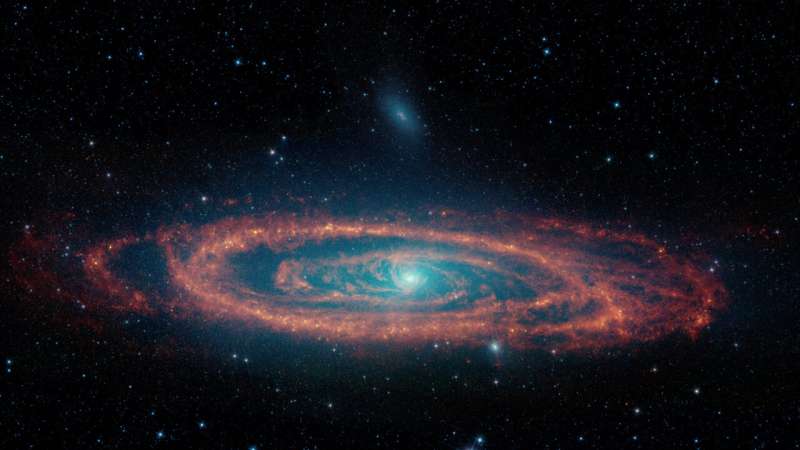

This image of the Andromeda galaxy uses data from NASA’s retired Spitzer Space Telescope. Multiple wavelengths are shown, revealing stars, dust, and areas of star formation. © NASA/JPL-Caltech

The simulation demonstrated that a small disk of hot gas could form close to the supermassive black hole and feed it continuously. The disk could be replenished and maintained by numerous streams of gas and dust.

However, the researchers also found that those streams have to stay within a particular size and flow rate; otherwise, the matter would fall into the black hole in irregular clumps, causing more light fluctuation.

When the authors compared their findings to data from Spitzer and NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, they found spirals of dust previously identified by Spitzer that fit within these constraints. From this, the authors concluded that the spirals are feeding Andromeda’s supermassive black hole.

“This is a great example of scientists reexamining archival data to reveal more about galaxy dynamics by comparing it to the latest computer simulations,” said Almudena Prieto, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands and the University Observatory Munich, and a co-author on the study published this year. “We have 20-year-old data telling us things we didn’t recognize in it when we first collected it.”

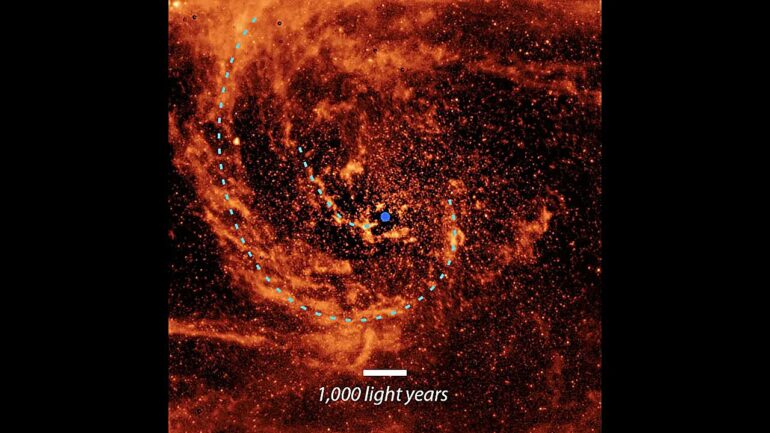

In this image of the Andromeda galaxy, also made with data from NASA’s retired Spitzer Space Telescope, only dust is visible, making it easier to see the galaxy’s underlying structure. © NASA/JPL-Caltech

A deeper look at Andromeda

Launched in 2003 and managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Spitzer studied the universe in infrared light, which is invisible to human eyes. Different wavelengths reveal different features of Andromeda, including hotter sources of light, like stars, and cooler sources, like dust.

By separating these wavelengths and looking at the dust alone, astronomers can see the galaxy’s “skeleton”—places where gas has coalesced and cooled, sometimes forming dust, creating conditions for stars to form. This view of Andromeda revealed a few surprises.

For instance, although it is a spiral galaxy like the Milky Way, Andromeda is dominated by a large dust ring rather than distinct arms circling its center. The images also revealed a secondary hole in one portion of the ring where a dwarf galaxy passed through.

Andromeda’s proximity to the Milky Way means it looks larger than other galaxies from Earth: Seen with the naked eye, Andromeda would be about six times the width of the moon (about 3 degrees). Even with a field of view wider than Hubble’s, Spitzer had to take 11,000 snapshots to create this comprehensive picture of Andromeda.

More information:

C. Alig et al, The Accretion Mode in Sub-Eddington Supermassive Black Holes: Getting into the Central Parsecs of Andromeda, The Astrophysical Journal (2023). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ace2c3

Citation:

NASA images help explain eating habits of massive black hole (2024, May 9)