Leveraging the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS), NASA Goddard Space Flight Center scientists ran 100 simulations exploring jets—narrow beams of energetic particles—that emerge at nearly light speed from supermassive black holes. These behemoths sit at the centers of active, star-forming galaxies like our own Milky Way galaxy, and can weigh millions to billions of times the mass of the sun.

As jets and winds flow out from these active galactic nuclei (AGN), they “regulate the gas in the center of the galaxy and affect things like the star-formation rate and how the gas mixes with the surrounding galactic environment,” explained study lead Ryan Tanner, a postdoc in NASA Goddard’s X-ray Astrophysics Laboratory.

“For our simulations, we focused on less-studied, low-luminosity jets and how they determine the evolution of their host galaxies.” Tanner said. He collaborated with X-ray Astrophysics Laboratory astrophysicist Kimberly Weaver on the computational study, which appears in The Astronomical Journal.

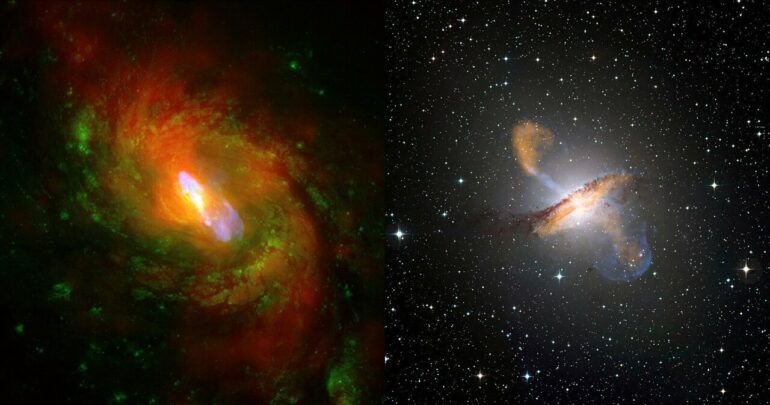

Observational evidence for jets and other AGN outflows first came from radio telescopes and later NASA and European Space Agency X-ray telescopes. Over the past 30 to 40 years, astronomers including Weaver have pieced together an explanation of their origin by connecting optical, radio, ultraviolet, and X-ray observations (see the next image below).

“High-luminosity jets are easier to find because they create massive structures that can be seen in radio observations,” Tanner explained. “Low-luminosity jets are challenging to study observationally, so the astronomy community does not understand them as well.”

The black hole jet simulations were performed on the 127,232-core Discover supercomputer at the NCCS. © NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab.

Enter NASA supercomputer-enabled simulations. For realistic starting conditions, Tanner and Weaver used the total mass of a hypothetical galaxy about the size of the Milky Way. For the gas distribution and other AGN properties, they looked to spiral galaxies such as NGC 1386, NGC 3079, and NGC 4945.

Tanner modified the Athena astrophysical hydrodynamics code to explore the impacts of the jets and gas on each other across 26,000 light-years of space, about half the radius of the Milky Way. From the full set of 100 simulations, the team selected 19—which consumed 800,000 core hours on the NCCS Discover supercomputer—for publication.

“Being able to use NASA supercomputing resources allowed us to explore a much larger parameter space than if we had to use more modest resources,” Tanner said. “This led to uncovering important relationships that we could not discover with a more limited scope.”

The simulations uncovered two major properties of low-luminosity jets:

They interact with their host galaxy much more than high-luminosity jets.They both affect and are affected by the interstellar medium within the galaxy, leading to a greater variety of shapes than high-luminosity jets.

“We have demonstrated the method by which the AGN impacts its galaxy and creates the physical features, such as shocks in the interstellar medium, that we have observed for about 30 years,” Weaver said. “These results compare well with optical and X-ray observations. I was surprised at how well theory matches observations and addresses longstanding questions I have had about AGN that I studied as a graduate student, like NGC 1386! And now we can expand to larger samples.”

More information:

Ryan Tanner et al, Simulations of AGN-driven Galactic Outflow Morphology and Content, The Astronomical Journal (2022). DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ac4d23

Provided by

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Citation:

NASA scientists create black hole jets with supercomputer (2022, November 29)