In a bold, strategic move for the U.S., acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy announced plans on Aug. 5, 2025, to build a nuclear fission reactor for deployment on the lunar surface in 2030. Doing so would allow the United States to gain a foothold on the Moon by the time China plans to land the first taikonaut, what China calls its astronauts, there by 2030.

Apart from the geopolitical importance, there are other reasons why this move is critically important. A source of nuclear energy will be necessary for visiting Mars, because solar energy is weaker there. It could also help establish a lunar base and potentially even a permanent human presence on the Moon, as it delivers consistent power through the cold lunar night.

As humans travel out into the solar system, learning to use the local resources is critical for sustaining life off Earth, starting at the nearby Moon. NASA plans to prioritize the fission reactor as power necessary to extract and refine lunar resources.

As a geologist who studies human space exploration, I’ve been mulling over two questions since Duffy’s announcement. First, where is the best place to put an initial nuclear reactor on the Moon, to set up for future lunar bases? Second, how will NASA protect the reactor from plumes of regolith – or loosely fragmented lunar rocks – kicked up by spacecraft landing near it? These are two key questions the agency will have to answer as it develops this technology.

Where do you put a nuclear reactor on the Moon?

The nuclear reactor will likely form the power supply for the initial U.S.-led Moon base that will support humans who’ll stay for ever-increasing lengths of time. To facilitate sustainable human exploration of the Moon, using local resources such as water and oxygen for life support and hydrogen and oxygen to refuel spacecraft can dramatically reduce the amount of material that needs to be brought from Earth, which also reduces cost.

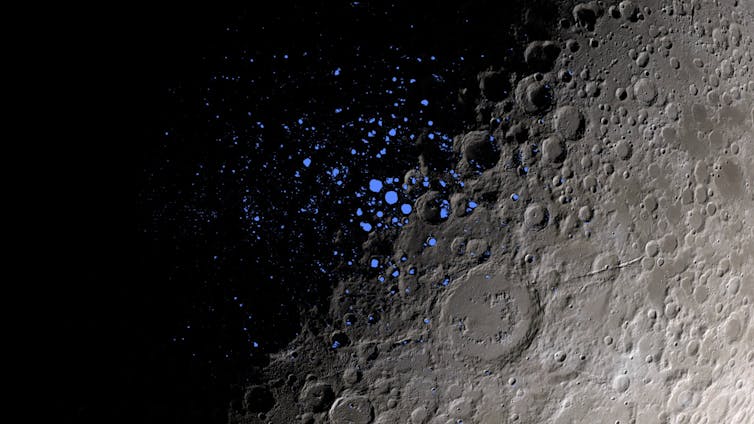

In the 1990s, spacecraft orbiting the Moon first observed dark craters called permanently shadowed regions on the lunar north and south poles. Scientists now suspect these craters hold water in the form of ice, a vital resource for countries looking to set up a long-term human presence on the surface. NASA’s Artemis campaign aims to return people to the Moon, targeting the lunar south pole to take advantage of the water ice that is present there.

Dark craters on the Moon, parts of which are indicated here in blue, never get sunlight. Scientists think some of these permanently shadowed regions could contain water ice.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

In order to be useful, the reactor must be close to accessible, extractable and refinable water ice deposits. The issue is we currently do not have the detailed information needed to define such a location.

The good news is the information can be obtained relatively quickly. Six lunar orbital missions have collected, and in…