Mars was once a very wet planet, as is evident in its surface geological features. Scientists know that over the last 3 billion years, at least some water went deep underground, but what happened to the rest? Now, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) missions are helping unlock that mystery.

“There are only two places water can go. It can freeze into the ground, or the water molecule can break into atoms, and the atoms can escape from the top of the atmosphere into space,” explained study leader John Clarke of the Center for Space Physics at Boston University in Massachusetts. “To understand how much water there was and what happened to it, we need to understand how the atoms escape into space.”

Clarke and his team combined data from Hubble and MAVEN to measure the number and current escape rate of the hydrogen atoms escaping into space. This information allowed them to extrapolate the escape rate backwards through time to understand the history of water on the red planet.

Their study is published in the journal Science Advances.

Escaping hydrogen and heavy hydrogen

Water molecules in the Martian atmosphere are broken apart by sunlight into hydrogen and oxygen atoms. Specifically, the team measured hydrogen and deuterium, which is a hydrogen atom with a neutron in its nucleus. This neutron gives deuterium twice the mass of hydrogen. Because its mass is higher, deuterium escapes into space much more slowly than regular hydrogen.

Over time, as more hydrogen was lost than deuterium, the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen built up in the atmosphere. Measuring the ratio today gives scientists a clue to how much water was present during the warm, wet period on Mars. By studying how these atoms currently escape, they can understand the processes that determined the escape rates over the last four billion years and thereby extrapolate back in time.

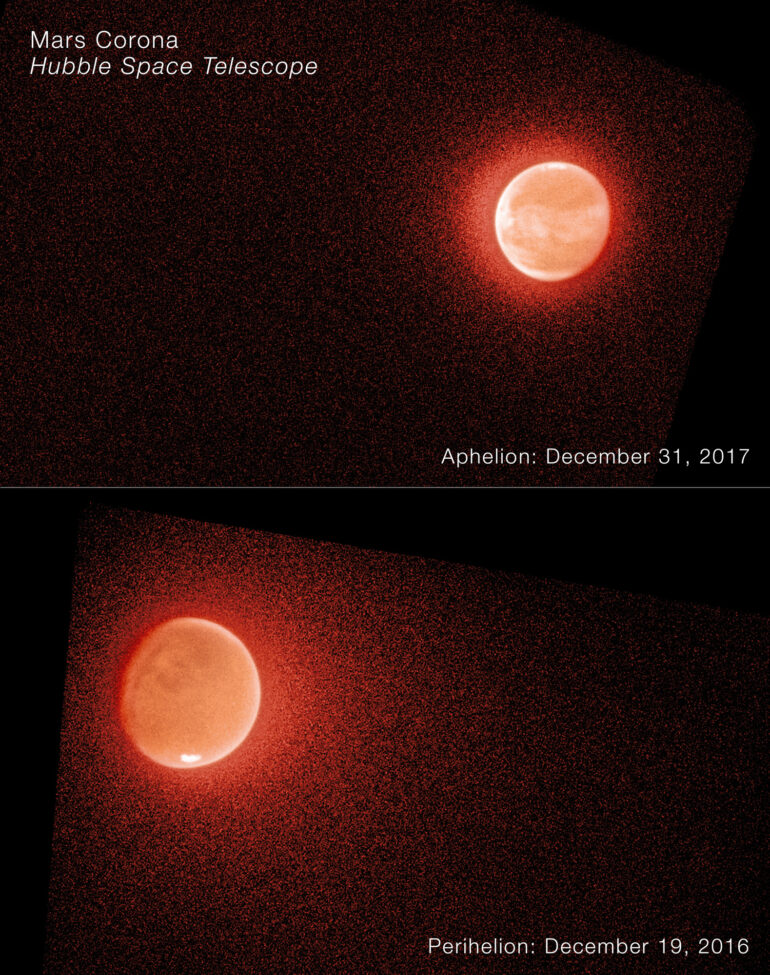

Although most of the study’s data comes from the MAVEN spacecraft, MAVEN is not sensitive enough to see the deuterium emission at all times of the Martian year. Unlike the Earth, Mars swings far from the sun in its elliptical orbit during the long Martian winter, and the deuterium emissions become faint. Clarke and his team needed the Hubble data to “fill in the blanks” and complete an annual cycle for three Martian years (each of which is 687 Earth days). Hubble also provided additional data going back to 1991—prior to MAVEN’s arrival at Mars in 2014.

The combination of data between these missions provided the first holistic view of hydrogen atoms escaping Mars into space.

A dynamic and turbulent Martian atmosphere

“In recent years, scientists have found that Mars has an annual cycle that is much more dynamic than people expected 10 or 15 years ago,” explained Clarke. “The whole atmosphere is very turbulent, heating up and cooling down on short timescales, even down to hours. The atmosphere expands and contracts as the brightness of the sun on Mars varies by 40 percent over the course of a Martian year.”

The team discovered that the escape rates of hydrogen and deuterium change rapidly when Mars is close to the sun. In the classical picture that scientists previously had, these atoms were thought to slowly diffuse upward through the atmosphere to a height where they could escape.

But that picture no longer accurately reflects the whole story, because now scientists know that atmospheric conditions change very quickly. When Mars is close to the sun, the water molecules, which are the source of the hydrogen and deuterium, rise through the atmosphere very rapidly releasing atoms at high altitudes.

The second finding is that the changes in hydrogen and deuterium are so rapid that the atomic escape needs added energy to explain them. At the temperature of the upper atmosphere, only a small fraction of the atoms have enough speed to escape the gravity of Mars. Faster (super-thermal) atoms are produced when something gives the atom a kick of extra energy. These events include collisions from solar wind protons entering the atmosphere, or sunlight that drives chemical reactions in the upper atmosphere.

Serving as a proxy

Studying the history of water on Mars is fundamental not only to understanding planets in our own solar system, but also the evolution of Earth-sized planets around other stars. Astronomers are finding more and more of these planets, but they’re difficult to study in detail.

Mars, Earth and Venus all sit in or near our solar system’s habitable zone, the region around a star where liquid water could pool on a rocky planet; yet all three planets have dramatically different present-day conditions. Along with its sister planets, Mars can help scientists grasp the nature of far-flung worlds across our galaxy.

More information:

John T. Clarke et al, Martian atmospheric hydrogen and deuterium: Seasonal changes and paradigm for escape to space, Science Advances (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adm7499

Citation:

NASA’s Hubble, MAVEN help solve the mystery of Mars’s escaping water (2024, September 5)