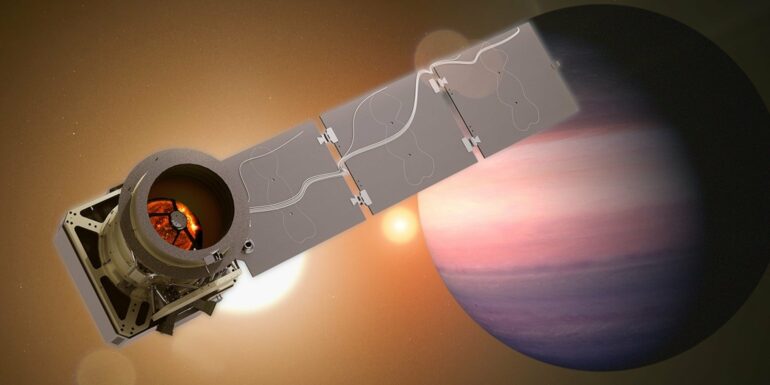

On Jan. 11, 2026, I watched anxiously at the tightly controlled Vandenberg Space Force Base in California as an awe-inspiring SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carried NASA’s new exoplanet telescope, Pandora, into orbit.

Exoplanets are worlds that orbit other stars. They are very difficult to observe because – seen from Earth – they appear as extremely faint dots right next to their host stars, which are millions to billions of times brighter and drown out the light reflected by the planets. The Pandora telescope will join and complement NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope in studying these faraway planets and the stars they orbit.

I am an astronomy professor at the University of Arizona who specializes in studies of planets around other stars and astrobiology. I am a co-investigator of Pandora and leading its exoplanet science working group. We built Pandora to shatter a barrier – to understand and remove a source of noise in the data – that limits our ability to study small exoplanets in detail and search for life on them.

Observing exoplanets

Astronomers have a trick to study exoplanet atmospheres. By observing the planets as they orbit in front of their host stars, we can study starlight that filters through their atmospheres.

These planetary transit observations are similar to holding a glass of red wine up to a candle: The light filtering through will show fine details that reveal the quality of the wine. By analyzing starlight filtered through the planets’ atmospheres, astronomers can find evidence for water vapor, hydrogen, clouds and even search for evidence of life. Researchers improved transit observations in 2002, opening an exciting window to new worlds.

When a planet passes in front of its star, astronomers can measure the dip in brightness, and see how the light filtering through the planet’s atmosphere changes.

For a while, it seemed to work perfectly. But, starting from 2007, astronomers noted that starspots – cooler, active regions on the stars – may disturb the transit measurements.

In 2018 and 2019, then-Ph.D. student Benjamin V. Rackham, astrophysicist Mark Giampapa and I published a series of studies showing how darker starspots and brighter, magnetically active stellar regions can seriously mislead exoplanets measurements. We dubbed this problem “the transit light source effect.”

Most stars are spotted, active and change continuously. Ben, Mark and I showed that these changes alter the signals from exoplanets. To make things worse, some stars also have water vapor in their upper layers – often more prominent in starspots than outside of them. That and other gases can confuse astronomers, who may think that they found water vapor in the planet.

In our papers – published three years before the 2021 launch of the James Webb Space Telescope – we predicted that the Webb cannot reach its full potential. We sounded the…