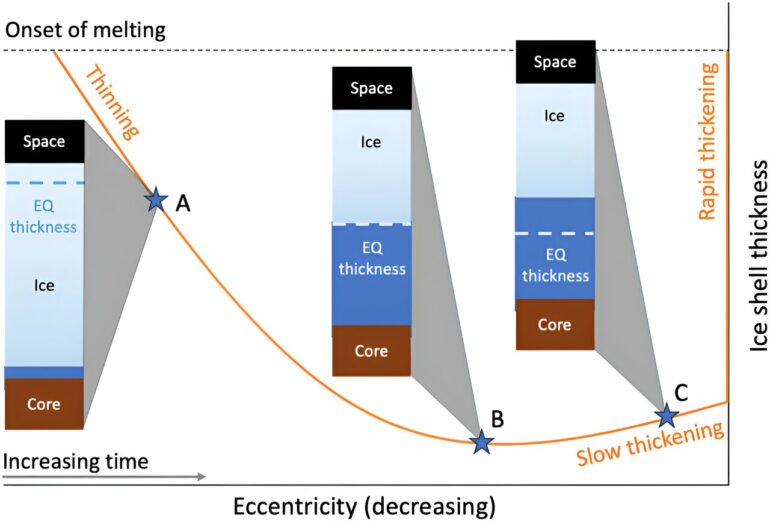

Saturn’s moon Mimas could have grown a huge underground ocean as its orbital eccentricity decreased to its present value and caused its icy shell to melt and thin.

“In our previous work, we found that for Mimas to be an ocean world today, it must have had a much thicker icy shell in the past. But because Mimas’s eccentricity would have been even higher in the past, the pathway to get from thick ice to thinner ice was less clear,” said Planetary Science Institute Senior Scientist Matthew E. Walker. “In this work we showed that there is a pathway for the ice shell to be thinning currently even as the eccentricity is dropping due to tidal heating, but the ocean must be very young, geologically speaking.”

Walker is co-author of “The evolution of a young ocean within Mimas”, which appears in Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Alyssa Rose Rhoden of the Southwest Research Institute is lead author.

“Eccentricity is what drives the tidal heating. Right now it is very high as compared with other active ocean moons, like neighboring Enceladus. We think that tidal heating is the heat source responsible for currently thinning the shell,” Walker said. “Tidal heating is not free energy though, so as it melts the shell, it pulls energy out of the orbit, which drops that eccentricity until it eventually circularizes it and shuts the whole thing down.”

The onset of melting had to occur when Mimas’s eccentricity was two to three times the present value. A thinning ice shell over the past 10 million years of Mimas’s evolution is consistent with its geology.

“Generally when we think of ocean worlds we don’t see a lot of craters because the environment is resurfaced and ends up erasing them, like Europa or the south pole of Enceladus. The shape, central peak, and undisrupted interior of Herschel crater require that the shell must have been thicker in the past, when Herschel formed. In order to get the crater morphology that we observe, the shell must have been at least 55 kilometers when it got hit,” Walker said.

“Craters can provide clues as to the presence of an ocean and the thickness of the ice shell through their morphology—such as the ratio between the crater diameter and its depth and the existence of a central peak.”

Mimas has a radius of just under 200 kilometers. The thickness of the outer hydrosphere, made up of ice and liquid, is roughly estimated to be around 70 kilometers. The current estimates of ice shell thickness are 20 to 30 kilometers, based on the precession (the rotational motion of the axis of a spinning body), or a narrower range of 24 to 31 kilometers from the libration (a slight wobble in the rotation rate of the moon that makes it appear to nod back and forth) measurements, leaving an ocean that is about 40 to 45 kilometers deep before it hits the rock.

“We may be seeing Mimas at a particularly interesting time. In order to match the current eccentricity and the thickness constraints based on the libration info, we think this whole thing must have started off no more than about 25 million years ago. In other words, we think Mimas was completely frozen until 10 to 25 million years ago, at which point its ice shell began melting. What changed to kick off that epoch of melting is still under investigation,” Walker said.

More information:

Alyssa Rose Rhoden et al, The evolution of a young ocean within Mimas, Earth and Planetary Science Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2024.118689

Provided by

Planetary Science Institute

Citation:

Orbital eccentricity may have led to young underground ocean on Saturn’s moon Mimas (2024, April 15)