Scientists have for the first time observed the early universe running in extreme slow motion, unlocking one of the mysteries of Einstein’s expanding universe. The research is published in Nature Astronomy.

Einstein’s general theory of relativity means that we should observe the distant—and hence ancient—universe running much slower than the present day. However, peering back that far in time has proven elusive. Scientists have now cracked that mystery by using quasars as “clocks.”

“Looking back to a time when the universe was just over a billion years old, we see time appearing to flow five times slower,” said lead author of the study, Professor Geraint Lewis from the School of Physics and Sydney Institute for Astronomy at the University of Sydney.

“If you were there, in this infant universe, one second would seem like one second—but from our position, more than 12 billion years into the future, that early time appears to drag.”

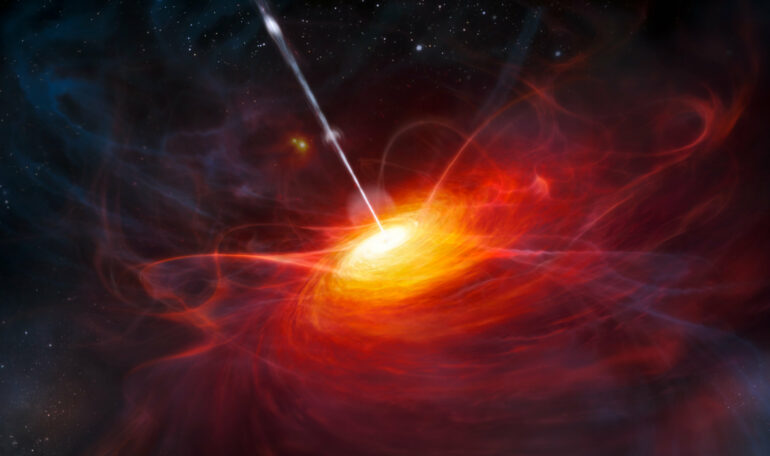

Professor Lewis and his collaborator, Dr. Brendon Brewer from the University of Auckland, used observed data from nearly 200 quasars—hyperactive supermassive black holes at the centers of early galaxies—to analyze this time dilation.

“Thanks to Einstein, we know that time and space are intertwined and, since the dawn of time in the singularity of the Big Bang, the universe has been expanding,” Professor Lewis said.

“This expansion of space means that our observations of the early universe should appear to be much slower than time flows today.

“In this paper, we have established that back to about a billion years after the Big Bang.”

Previously, astronomers have confirmed this slow-motion universe back to about half the age of the universe using supernovae—massive exploding stars—as “standard clocks.” But while supernovae are exceedingly bright, they are difficult to observe at the immense distances needed to peer into the early universe.

By observing quasars, this time horizon has been rolled back to just a tenth the age of the universe, confirming that the universe appears to speed up as it ages.

Professor Lewis said, “Where supernovae act like a single flash of light, making them easier to study, quasars are more complex, like an ongoing firework display.

“What we have done is unravel this firework display, showing that quasars, too, can be used as standard markers of time for the early universe.”

Professor Geraint Lewis in the Sydney Institute for Astronomy in the School of Physics at the University of Sydney. © The University of Sydney

Professor Lewis worked with astro-statistician Dr. Brewer to examine details of 190 quasars observed over two decades. Combining the observations taken at different colors (or wavelengths)—green light, red light and into the infrared—they were able to standardize the “ticking” of each quasar. Through the application of Bayesian analysis, they found the expansion of the universe imprinted on each quasar’s ticking.

“With these exquisite data, we were able to chart the tick of the quasar clocks, revealing the influence of expanding space,” Professor Lewis said.

These results further confirm Einstein’s picture of an expanding universe but contrast earlier studies that had failed to identify the time dilation of distant quasars.

“These earlier studies led people to question whether quasars are truly cosmological objects, or even if the idea of expanding space is correct,” Professor Lewis said.

“With these new data and analysis, however, we’ve been able to find the elusive tick of the quasars and they behave just as Einstein’s relativity predicts,” he said.

More information:

Detection of the cosmological time dilation of high-redshift quasars, Nature Astronomy (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-023-02029-2 , www.nature.com/articles/s41550-023-02029-2

Source data for this project is available at zenodo.org/record/5842449#.YipOg-jMJPY

Provided by

University of Sydney

Citation:

Quasar ‘clocks’ show the universe was five times slower soon after the Big Bang (2023, July 3)