A team of astronomers announced on April 16, 2025, that in the process of studying a planet around another star, they had found evidence for an unexpected atmospheric gas. On Earth, that gas – called dimethyl sulfide – is mostly produced by living organisms.

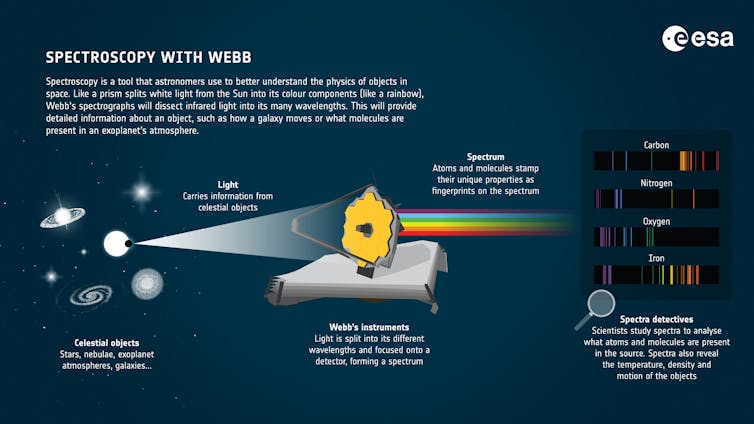

In April 2024, the James Webb Space Telescope stared at the host star of the planet K2-18b for nearly six hours. During that time, the orbiting planet passed in front of the star. Starlight filtered through its atmosphere, carrying the fingerprints of atmospheric molecules to the telescope.

JWST’s cameras can detect molecules in the atmosphere of a planet by looking at light that passed through that atmosphere.

European Space Agency

By comparing those fingerprints to 20 different molecules that they would potentially expect to observe in the atmosphere, the astronomers concluded that the most probable match was a gas that, on Earth, is a good indicator of life.

I am an astronomer and astrobiologist who studies planets around other stars and their atmospheres. In my work, I try to understand which nearby planets may be suitable for life.

K2-18b, a mysterious world

To understand what this discovery means, let’s start with the bizarre world it was found in. The planet’s name is K2-18b, meaning it is the first planet in the 18th planetary system found by the extended NASA Kepler mission, K2. Astronomers assign the “b” label to the first planet in the system, not “a,” to avoid possible confusion with the star.

K2-18b is a little over 120 light-years from Earth – on a galactic scale, this world is practically in our backyard.

Although astronomers know very little about K2-18b, we do know that it is very unlike Earth. To start, it is about eight times more massive than Earth, and it has a volume that’s about 18 times larger. This means that it’s only about half as dense as Earth. In other words, it must have a lot of water, which isn’t very dense, or a very big atmosphere, which is even less dense.

Astronomers think that this world could either be a smaller version of our solar system’s ice giant Neptune, called a mini-Neptune, or perhaps a rocky planet with no water but a massive hydrogen atmosphere, called a gas dwarf.

Another option, as University of Cambridge astronomer Nikku Madhusudhan recently proposed, is that the planet is a “hycean world”.

That term means hydrogen-over-ocean, since astronomers predict that hycean worlds are planets with global oceans many times deeper than Earth’s oceans, and without any continents. These oceans are covered by massive hydrogen atmospheres that are thousands of miles high.

Astronomers do not know yet for certain that hycean worlds exist, but models for what those would look like match the limited data JWST and other telescopes have collected on K2-18b.

This is where the story becomes exciting. Mini-Neptunes and gas dwarfs are unlikely to be hospitable for…