Every galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center, much like every egg has a yolk. But sometimes, hens lay eggs with two yolks. In a similar way, astrophysicists like us who study supermassive black holes expect to find binary systems – two supermassive black holes orbiting each other – at the hearts of some galaxies.

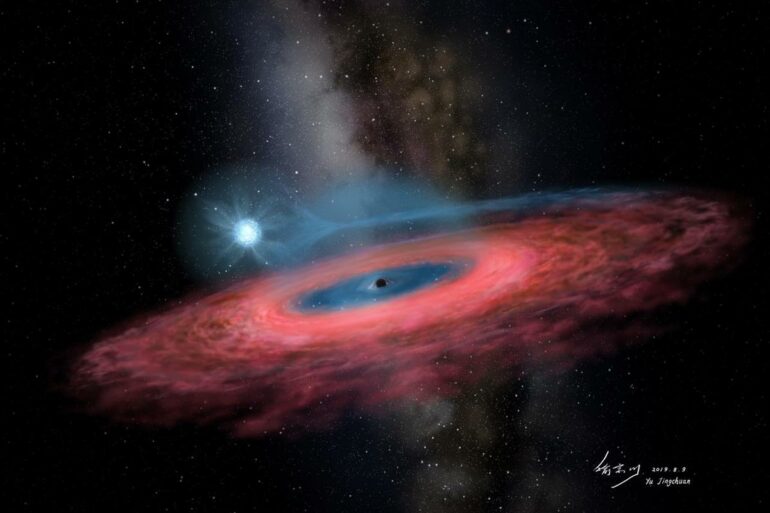

Black holes are regions of space where gravity is so strong that not even light can escape from their vicinity. They form when the core of a massive star collapses on itself, and they act as cosmic vacuum cleaners. Supermassive black holes have a mass a million times that of our Sun or larger. Scientists like us study them to understand how gravity works and how galaxies form.

Figuring out whether a galaxy has one or two black holes in its center isn’t as easy as cracking an egg and examining the yolk. But measuring how often these binary supermassive black holes form can help researchers understand what happens to galaxies when they merge.

In a new study, our team dug through historical astronomical data dating back over a hundred years. We looked for light emitted from one galaxy that showed signs of harboring a binary supermassive black hole system.

Galactic collisions and gravitational waves

Galaxies like the Milky Way are nearly as old as the universe. Sometimes, they collide with other galaxies, which can lead to the galaxies merging and forming a larger, more massive galaxy.

The two black holes at the center of the two merging galaxies may, when close enough, form a pair bound by gravity. This pair may live for up to hundreds of millions of years before the two black holes eventually merge into one.

Supermassive black holes orbiting around each other can emit gravitational waves.

Binary black holes release energy in the form of gravitational waves – ripples in space-time that specialized observatories can detect. According to Einstein’s general relativity theory, these ripples travel at the speed of light, causing space itself to stretch and squeeze around them, kind of like a wave.

Pulsar timing arrays use pulsars, which are the dense, bright cores of collapsed stars. Pulsars spin very fast. Researchers can look for gaps and anomalies in the pattern of radio waves emitted from these spinning pulsars to detect gravitational waves.

While pulsar timing arrays can detect the collective gravitational wave signal from the ensemble of binaries within the past 9 billion years, they’re not yet sensitive enough to detect the gravitational wave signal from a single binary system in one galaxy. And even the most powerful telescopes can’t image these binary black holes directly. So, astronomers have to use clever indirect methods to figure out whether a galaxy has a binary supermassive black hole in its center.

Searching for signs of binary black holes

One type of indirect method involves searching for periodic signals from…